Azerbaijan: A Brief Information of the Country’s Energy Policy

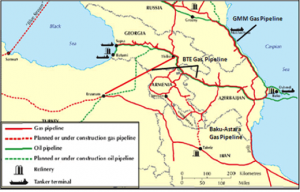

As a landlocked energy exporter, Azerbaijan’s oil export infrastructure crosses neighboring states before accessing world markets.[1] Baku’s preference of an east-west route through Georgia and Turkey for its main energy export pipeline route echoes its primary alliance orientation in the 1990s. By preferring the route through Georgia and Turkey, Baku identified that a security alliance with these states was the most beneficial of its countless options. In addition, a landlocked state inclines to decide on as its transit state one that do have the strongest interest in keeping up the flow of trade through its territory and therefore least likely to interrupt it in the service of foreign policy and other goals. Thus, Georgia was chosen as Azerbaijan’s major transit state. During the independence period, Azerbaijan’s assessment of the role of energy export as a foreign policy tool has changed. The Azerbaijani leadership appraised that its role as an energy exporter would constitute a strong interest on the part of the U.S. and Europe in stability in the South Caucasus, and thus they would actively work towards the resolution of the Nagorno – Karabakh conflict.

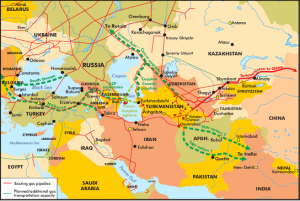

For satisfying the increasing energy demand and diversify its supply options, by decreasing natural gas monopoly in European markets, the European Union has initiated the Southern Gas Corridor in order to realize the flow of natural gas to markets from the Caspian region. At its current point, the development of the westward supply chain from the region has been negatively affected by several impediments, but one can talk about some developments regarding this issue.[2] The major obstacles can be put forward as follows: First, the land-locked nature of the Caspian region limits supply options and do increase the dependency of the energy producing states on transportation in neighboring states. Since neither Baku nor Ashgabat do have direct access to the high seas, they require transit pipelines to gain access for accessing the European energy markets. The increase of investment in hydrocarbon production and advancement of new pipeline projects taken mostly the Azeri gas as the basis have importantly increased the role of Baku’s role as an energy country. In today’s world, gas supply to Southern and Eastern European markets, via the southern gas corridor is the central point of concentration of Baku’s energy strategy. Furthermore, the beginning supply of gas through the southern gas corridor is hoped to flow from its Shah Deniz field, one of the world’s largest gas fields. Nabucco, Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, Interconnector-Turkey-Greece-Italy and South-East Europe Pipeline have been struggling for the privileges to bring Shah Sea gas to Europe.

But exporting gas from Baku encounters challenges that arise from the factors such as geopolitics, the region’s landlocked geography and clashing interests of fundamental players, limits of transportation options, and the requirement for a transit pipeline to bring natural gas to European markets, As a result, the government in Baku has put forward the following guidelines:

- Elude or curtail transit risks by having the majority share in export/energy infrastructure in transit states;

- Diversify pipelines routes by advancing multiple-export options and;

- Follow a market-based policy.

Baku and Ankara signed a gas sale and transportation agreement on June 7, 2010. Taner Yıldız, Turkey’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, mentioned that the new price Ankara has to pay for gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz project is higher than the previous price of $120 per 1,000 cubic meters. Yıldız did not give an exact figure. A SOCAR source stated that the envisaged price would be $250/tcm. CNN-Turk, however, has conveyed an agreed price of $300/tcm. The two partners also reportedly agreed on the price and volume of Azerbaijan gas supplies to Turkey from Shah Deniz after 2016, when the second phase of production is planned to reach 16 bcm. Ankara had safeguarded the privilege to buy 2 bcm of gas in 2016, 4 bcm in 2017, and 6 bcm in 2018. A third deal permits Baku to establish a company in Turkey to deal with the issues on gas transit to Europe via Turkish territory. A separate deal between SOCAR and BOTAŞ set up the conditions and mechanism for gas sales and shipment.

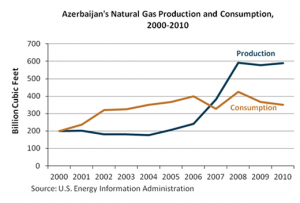

Baku has augmented exports from the huge Shah Deniz field, with an upturn of 98,200,000 cubic meters of gas last month exported through the South Caucasus pipeline, compared to the same period last year. The increase sees exports through this pipeline, total 434.700,000 cubic meters of gas in January of 2012. This month’s increase is followed by a drop in export in 2011 from 2010’s export amounts, which totally amounted to 4.5 bcm of gas for last year, a drop of 400 million cubic meters on the previous year.

The war between Moscow and Tblisi in 2008 caused the brief closure of the SCGP and the shutting down of three months of the oil pipeline connecting Baku with Georgian part of Supsa. Russian forces besieged bridges and railroads and obstructed Georgian ports thereby hampering Azerbaijani oil exports.[3] These actions seriously cast doubts on the safety of Georgia as an energy-transit state as well as the future of Ankara as an energy conduit given that hydrocarbons from the Caspian region were hoped to transit Georgia before reaching Turkey. But Russian aggression did force politicians in Europe to give more immediate attention to the offered southern gas corridor to diversify their sources of gas imports and decrease energy dependence on Moscow.

The Caucasus continued to be a highly volatile region. The conflict between Baku and Yerevan over Nagorno-Karabakh was still unresolved.[4] The renewed confrontation over the enclave could result in strikes against the BTC and the SCGP, less than 20 kilometers from the frontline, where Armenian and Azerbaijani forces confront each other in a tense stand-off. Holding large scale military exercises in October 2012, the Armenian general staff expressed that they could destroy Azerbaijani energy facilities by missile attack.

The BTC pipeline was closed for over two weeks after an explosion at an above-ground valve in Erzincan province on August 5, 2008. The Turkish authorities attributed this to technical problems, but the PKK appealed responsibility.[5] An attack on the showpiece BTC pipeline in north-eastern Turkey, far from the PKK’s usual area of operations in the southeast, questioned the safety of Turkey as an energy-transit state. Though any additional attacks on the BTC have been reported, AKP officials would have been alarmed that in May and October 2012, the SCGP was hit by what seems to have been PKK sabotage. Gas flows along the pipeline, through which future production from Shah Deniz may be carried, were broken up for a total of three weeks. Not surprisingly, the Turkish authorities have searched for downplaying the importance of these attacks.

Source: Central Asia Caucasus Institute

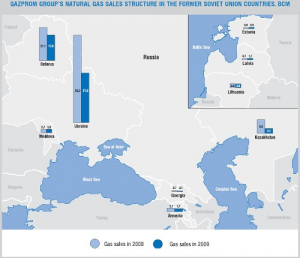

As negotiation of a potential Nagorno-Karabakh deal speeds up, Baku seems to be making serious overtures toward Moscow in expecting that the Kremlin will force Yerevan to make key concessions.[6] As an incentive, Baku is playing one of its most strategic cards – collaboration in the natural gas sector. During a joint press conference with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on April 17, 2009, Azerbaijani leader Ilham Aliyev indicated that he does “not see any restriction” on potential gas sales of Azerbaijan to Russia. The assertion has been comprehended to include gas sales from Stage 2 of the multilateral Shah Deniz project, expected to produce 14-16 billion cubic meters of gas annually. He also stated that oil transportation via the Baku-Novorossiysk pipeline could also augment.

An energy supply deal was signed between Russian and Azerbaijani officials that are likely to revive serious questions about the fate of the EU’s probable Nabucco gas pipeline. The deal to commence the stream of Azerbaijani gas to Russia in January 2010 symbolizes a step forward as both Moscow and the European Union court Baku in hopes of tapping its vast gas deposits to fuel favored pipeline projects to Europe.[7] Visiting Russian President Dmitry Medvedev expressed on June 29 that Moscow and Baku were “very significant suppliers of energy resources” who would work up far-reaching oil collaboration with new cooperation in the gas sector. What is vibrant is that Russia will begin getting Azerbaijani gas on the first day of 2010 and the volume will initially be a modest 500 million cubic meters per year. Gazprom’s Miller stated that his company “can buy gas quickly” from Azerbaijan, since their neighborhood status enables the non-requirement of third-party agreements on transit and there exists already a pipeline linking the two countries. In what could be a setback to expectations for the Nabucco project, Miller argued that Gazprom has become a chosen buyer for the second half of Azerbaijan’s offshore Shah Deniz gas field.

Trans-Anatolia Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP)

TANAP targets the transportation of gas to be produced in Shah Deniz 2 field and other fields of Azerbaijan (and other possible neighboring countries) via Turkey to Europe. A MOU was signed by the president of SOCAR, Rövnag Abdullayev, and Vice General Manager of BOTAŞ, Mehmet Konuk on December 26, 2011 in Ankara.[8] SOCAR, BOTAŞ and/or TPAO formed a joint consortium. On June 26, 2012, an agreement regarding the construction of TANAP was signed by Taner Yıldız, and Minister of Energy of Azerbaijan, Natık Aliyev. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and President Aliyev put their signatures on this agreement as the witnesses.

The Host Country Agreement was signed between Taner Yıldız and Rövnag Abdullayev. This project is envisaged to cost as 7 billion dollars. The partners of the project will finance the construction of the pipeline comparatively with their shares (SOCAR: 80%, BOTAŞ: 5%, TPAO: 15%). As the third party, gas producing companies, to mean the partners of Shah Sea Consortium, can be allowed to participate the consortium later.[9] The Shah Sea consortium consists of BP: 25.5%, Norwegian Statoil: 25.5%, SOCAR, TOTAL, LUKOİL, Iran NICO, each of them have 10% shares and TPAO: 9%. Transit line capacity has initially been designed as 16 bcm. According to the long term agreement between Turkey and Azerbaijan, the former will reserve the right to buy 6 bcm annually from Shah Deniz at the second phase of production as of 2017. The rest 10 bcm will be delivered on the border of Bulgaria and/or Greece via TANAP. Within the context of newly signed MOU, after the feasibility studies of this pipeline in the beginning of 2012, Baku and Ankara will start the construction in 2014-2015 and will complete the pipeline in 2018. The year 2018 corresponds to the year that the annual 16 bcm Shah Deniz production will begin. It is envisioned that the capacity will reach to 23 bcm in 2023 and to 31 bcm level in 2026. The project is also considered as an alternative line for the transmission of Turkmen gas to Turkey and Europe in the future.

Source: http://www.tanap.com/proje-fotograf-galerisi

According to Taner Yıldız, TANAP will back noticeably to the diversification of Ankara’s gas portfolio, and to Turkey’s national energy supply security.[10] Moreover, TANAP will undertake the central role in Ankara’s mission of becoming a “bridge” for carrying the rich energy resources of the East to the West where the demand increases. If Europe, Asia and Africa are considered as a continuum, Turkey can be defined as the “Artery of Energy.” Therefore, after the BTC, SCGPL, ITGI, and Kirkuk-Ceyhan Oil Pipeline, TANAP will form the last and perhaps most central component of this “Artery” function. This project has important strategic value for Turkey, Azerbaijan and European countries. For Ankara, the fact that the Turkish market will be supplied with a volume of gas coming via the TANAP system is significant for Ankara’s supply security and for its strategic target of turning out to be an energy hub and bridge. From Baku’s perspective, the pipeline will offer direct access to European markets via an alternative route, and allow carrying its gas to a wider range of markets, therefore open the way for other gas fields in Azerbaijan to be advanced. From European countries’ perspective, they might match their augmenting gas demand from an alternative source and via alternative route.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ranks fourth in the world behind those of Russia, Iran and Qatar in terms of natural gas reserves and sixth in the world in terms of natural gas production behind those of U.S., Russia, Iran, Qatar, Canada, China and Saudi Arabia according to BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013.[11] Yet the country faces several challenges in bringing those reserves to world market. It is situated far from end-use markets and lacks necessary pipeline infrastructure to export more hydrocarbons.

Moreover, its ability is limited by the fact that the country is essentially surrounded by competing hydrocarbon-rich Central Asian and Caspian states with more favorable investment climates and greater access to markets and, until recently, the country had only one major export pipeline route. The country recognizes the need to diversify export routes for its oil and gas resources outside of the pipelines going to Russia and create a more business-friendly environment by attempting to attract foreign investment for increasing both oil and gas production and expanding its export portfolio. In this respect, the Government of Turkmenistan has launched legal reforms on foreign investment by adopting new edition of the Law on Foreign Investment in October 2008 and the Law on Hydrocarbon Resources regulating offshore and onshore petroleum operations in Turkmenistan, including petroleum licensing, taxation, accounting and other rights and obligations of state agencies and foreign partners in August 2008. Consequently, Turkmenistan is constantly moving towards improvement of the investment climate. Yet the laws adopted to regulate foreign investment have not been consistently or effectively implemented and decisions to allow foreign investment are still politically driven. Apparently, the country’s economy is predominantly regulated by the state.[12]

Kaynak: http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/cabs/Turkmenistan/images/Natural%20Gas%20map.gif

Kremlin’s chasing after its energy interests in abroad angers the White House. In terms of controlling the Central Asia and Caucasia regions, the oil and gas constitute the single most important catalyst for Russia for achieving its target of forming a system just like in Soviet Union.[13] On the one hand, the United States has been successful in the construction of Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan Crude Oil Pipeline. Washington also attempts to convince the possible investors as well as Central Asian states to Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline Project that will be constructed under the Caspian Sea. On the other hand, Kremlin has guaranteed the commitments from Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan on the augmentation of exportation of Central Asia hydrocarbon resources via using Russia’s pipelines. For instance, in an agreement made between the presidents of Russian Federation and Turkmenistan in 2003, the latter is going to sell most of its natural gas to Russia till 2028.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan proven oil reserves are 30 billion barrels which are located in the Western Part of the country. Kazakhstan as an oil producer since 1911 has the second largest oil reserves as well as the second largest oil production among the former Soviet Republics. In addition, rising natural gas production over the last decade has transformed Kazakhstan from a net gas importer country to a country self-sufficient in 2011. Natural Gas: Most of Kazakhstan’s natural gas reserves located in just four fields: Karachaganak, Tengiz, Imashevskoye, and Kashagan. Since 2008, country produces sufficient volume of natural gas to satisfy its domestic demand. However due to lack of proper infrastructure in production linking the demand centers of production areas, the country needs to gas imports.

The sector organization for the country since March 2010 has driven by two ministries; Ministry of Oil and Gas and the Ministry for Industries and New Technologies responsible for the petroleum sector. Also, state has a central role in the oil and gas sector. However, Kazakhstan has some disadvantages in international energy markets namely; lack of domestic gas pipeline infrastructure and lack of export pipelines. Yet, Kazakhstan is a land –locked country, which has distance from international oil markets. Moreover, China and Russia are the key partners who provide sources of export demand and government project financing. Most of the current pipeline system was developed as a part of the Soviet System, and its goal was to maximize transport of oil for Russia, following the break-up of Soviet Union Kazakhstan was wholly dependent on Russia for its exports, giving Russia complete control of Kazakhstan exports. Trans-Caspian Tankers and a pipeline to China are important in order to reduce its dependence on Russia’s infrastructure.

Regarding Kazakhstan, Moscow and Astana signed an agreement on the distribution of Kazakh oil on June 6, 2002.[14] By this agreement, when Kremlin accepts the possession of Kurmangazy, rich oil basin in the Caspian Sea, to Astana, in return for this, it has ensured to make joint investments with this country and guarantees on the carrying of Kazakh oil via Russia through the Tengiz-Novorossik pipeline to Western markets which will be drilled from this basin. Moscow, together with Ashgabat and Astana will develop and extend the already functioning Soviet-era Central Asia-Center pipeline system. The agreement would permit Moscow to supply Central Asian gas at below-market prices to its quickly developing economy, while the Russian gas will be exported to Europe.[15] The modernization and enlargement of this pipeline, and the proposed construction of a similar pipeline extending up the Caspian coast from Ashgabat through Astana to Moscow, will augment the exports of Central Asian gas to Moscow from 60 bcm/year to 90 bcm/year. It is envisaged that the initial enlargement of 10 bcm / year would occur by 2009 and full capacity would have been accessed as early as 2010. The agreement between Kremlin, Ashgabat and Astana was a key victory for Russia and has strengthened the increasingly central role Kremlin’s pipeline system performs in the global energy sector.[16]

Source: http://www.gazprom.com/about/production/projects/pipelines/central-asia/

Business in Kazakhstan is often focused on the oil and gas sector which has created a boom in country’s economy. As being the leading market in Central Asia, Kazakhstan is positioning itself as a transit role between China and Europe. In addition like other former Soviet Republics, Kazakhstan is still developing a transparent and effective business culture in order to attract more foreign investment. Yet, new laws and regulation are often incorrect implemented at the local level. Also, challenges remain in the country’s competitiveness and economic diversification. If economic highlights of Kazakhstan are examined, according to the recent rapport of Heritage Foundation’s Index of Freedom, Kazakhstan has rated as ‘moderately free’ and ranked 65th out of 179 countries. Moreover, according to the World Bank data country has moved up on the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Report for 2012, ranking 47th to out of 183. (An 11 place jump up from 2011).[17]

Moscow, together with Ashgabat and Astana will develop and extend the already functioning Soviet-era Central Asia-Center pipeline system. The agreement would permit Moscow to supply Central Asian gas at below-market prices to its quickly developing economy, while the Russian gas will be exported to Europe.[18] The modernization and enlargement of this pipeline, and the proposed construction of a similar pipeline extending up the Caspian coast from Ashgabat through Astana to Moscow, will augment the exports of Central Asian gas to Moscow from 60 bcm/year to 90 bcm/year. It is envisaged that the initial enlargement of 10 bcm / year would occur by 2009 and full capacity would have been accessed as early as 2010. The agreement between Kremlin, Ashgabat and Astana was a key victory for Russia and has strengthened the increasingly central role Kremlin’s pipeline system performs in the global energy sector.[19]

Given the current appropriate prices and appropriate transportation systems, Caspian states will be less reluctant on the construction of new pipelines proposed by non-Russian states.[20] The Prikaspiskiy Pipeline Project illustrates the best example of the partnership between Moscow, Ashgabat and Astana. Other than this, the autocratic regimes in Central Asia are contented with their conditions due to Russia’s not intending to democratize them.

Source: http://www.gazprom.com/about/marketing/cis-baltia/

Sina KISACIK & Ayhan GÜCÜYENER & Ali ŞENYURT

[1] Brenda Shaffer, “Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy since Independence,” Caucasus International, Vol. 2, No. 1, (2012): p. 81.

[2] Sevinj Mammadova, “Natural Gas Supply to Europe: Azerbaijan’s Energy Policy”, Caucasus International, Vol. 2, No. 3, (2012): pp. 160-161.

[3] Gareth M. Winrow, “The Southern Gas Corridor and Turkey’s Role as an Energy Transit State and Energy Hub,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 15, No. 1, (2013): pp. 156-157.

[4] “Nagorno-Karabakh: Risking War”, International Crisis Group, Europe Report No. 187, November 14, 2007, accessed February 11, 2013, http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/europe/187_nagorno_karabakh___risking_war.pdf, p. 14.

[5] “Turkish ministry: Explosion on Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline a terror act,” Trend Az, October 4, 2012, accessed February 11, 2013, http://en.trend.az/capital/energy/2072926.html.

[6] Shahin Abbasov, “Azerbaijan: Is Baku Offering a Natural Gas Carrot to Moscow for Help with Karabakh?,” Eurasianet, April 19, 2009, accessed February 02, 2013, http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insightb/articles/eav042009a.shtml.

[7] Bruce Pannier, “Russia, Azerbaijan Achieve Gas Breakthrough,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 30, 2009, accessed February 02, 2013, http://www.rferl.org/content/Russia_Azerbaijan_Achieve_Gas_Breakthrough/1766221.html.

[8] “What is TANAP?,” TANAP Company, http://www.tanap.com/en/what-is-tanap, accessed January 08, 2013.

[9] Burcu Gültekin Punsmann, “Azerbaycan-Türkiye İlişkilerinde Bir Adım: Trans Anadolu Boru Hattı (TANAP),” Hazar Raporu, No.1, October-December 2012: pp. 17-18.

[10] “Interview with Taner Yıldız,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 3, (2012), p. 32.

[11] British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013, pp. 6-23. http://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/statistical-review/statistical_review_of_world_energy_2013.pdf [04.07.2013].

[12] Energy Information Administration(EIA), Turkmenistan-Country Analysis Brief, January 2012 ,p. 1-3, http://www.eia.gov/EMEU/cabs/Turkmenistan/pdf.pdf [04.07.2013] ; Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC), Guide to Doing Business and Investing in Turkmenistan, 2011, pp. 4-6, http://www.pwc.com/uz/en/dbg_tkm_2011.pdf [04.07.2013].

[13] Ariel Cohen, “Russia: The Flawed Energy Superpower,” in Energy Security Challenges for the 21st Century: A Reference Handbook, eds. Gal Luft and Anne Korin (United States of America: Praeger Security International, 2009), p. 97.

[14] Vladimir Socor, “Major Russia-Kazakhstan Oil Production-Sharing Agreement Signed,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol. 2, No. 131, July 07, 2005, accessed January 12, 2013, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=30623&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=176&no_cache=1.

[15] “Central Asia: Russian, Turkmen, Kazakh Leaders Agree on Caspian Pipeline,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 12, 2007, accessed January 16, 2013, http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1076429.html.

[16] M.K. Bhadrakumar, “A massive wrench thrown in Putin’s works,” Asia Times Online, September 29, 2007, accessed January 16, 2013, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Central_Asia/II29Ag01.html.

[18] “Central Asia: Russian, Turkmen, Kazakh Leaders Agree on Caspian Pipeline,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 12, 2007, accessed January 16, 2013, http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1076429.html.

[19] M.K. Bhadrakumar, “A massive wrench thrown in Putin’s works,” Asia Times Online, September 29, 2007, accessed January 16, 2013, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Central_Asia/II29Ag01.html.

[20] Gregory Gleason, “Russia and Central Asia’s Multivector Foreign Policies” in After Putin’s Russia: Past Imperfect, Future Uncertain, eds. Stephen K. Wegren and Dale R. Herspring (United States of America: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2010), pp. 254-255.