Abstract: Turkish foreign policy has gone through important changes since its establishment due to changing internal and international conditions. Even though its major orientation remained the same as well as its basic principles, the transformation of the global balance of power had important impacts over the Turkish diplomacy. In the last decade, marked by the outcome of the September 11 attacks in the international level and the AK Party rule in Turkey, the latter has taken important foreign policy decisions, which are mainly influenced by Ahmet Davutoğlu’s geopolitical approach, on how to deal with the new issues of the international scene. These can be seen both a continuation of Turkey’s traditional diplomacy line and a new vision implemented to better serve Turkey’s national interests.

Key Words: Turkish Foreign Policy, International Politics, Strategy, International Security, National Interest.

Introduction

One of the important features of states in the international system is to form and follow a foreign policy of their own. Turkey is no exception in that regard. The Turkish foreign policy targets the establishment, consolidation and development of a regional and international environment based on stability, cooperation and economic growth especially in the surrounding region. Independence, national sovereignty and respect for international law form this policy’s framework.

Under the bipolar system that has emerged in the wake of the WWII, Turkish foreign policy has been shaped within western values and principles, namely modernization and national sovereignty. After the end of Cold War, Turkish foreign policy undertook an effort of transformation all along the 1990s. In 2000s, especially with the accession of the AK Party (Justice and Development Party) to power in November 2002, several new initiatives and tendencies have been experienced in the foreign policy area affecting Turkey’s international relations.

In this context, this paper aims to emphasize the Turkey’s changing foreign policy and the new line Ankara has adopted in the last years. In order to better understand this change and its differences from Turkey’s traditional foreign policy, a brief summary of Turkish foreign policy will be displayed and its periods will be discussed. The Turkish foreign policy since 2002 will be mentioned in the second part of the paper. In that part, the main foreign policy parameters of AK Party will firstly be analyzed in detail. The debate on the so-called “Axis Shift” in Turkish foreign policy will be discussed in the final part of the paper.

1. Fundamental Factors and Guiding Principles of Turkish Foreign Policy

Gözen points out that the Turkish foreign policy includes plans, programs, strategies and policies developed by Turkey in order to realize targets and ideals seen as the national interest of Ankara in the international arena.[1] Ottoman background and history, national power and the balances of the international system are the three fundamental pillars of Turkish foreign policy. These factors play sometimes a limitative and sometimes a catalyst role in determining the Turkey’s role in the world politics, Ankara’s approach toward other countries and regions as well as toward contemporary global problems.

Sanberk discusses that Westernization, the quasi-sanctity of the National Pact adopted in 1920, and Atatürk’s “Peace at home, Peace in the world” principles have been the unmovable parameters of Turkish foreign policy since the establishment of the Turkish Republic.[2] According to Sanberk, foreign policies of are derivative of countries’ founding principles. As long as these principles remain unchanged, the parameters of Turkish foreign policy will remain the same as well.

1.1 Turkish Foreign Policy under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s Presidency

This period begins from the proclamation of the republic on October 29th, 1923, and ends with the death of Turkey’s first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, on November 10th, 1938. As an independent state and a sovereign actor of the international system, Turkey has followed a classical balance of power policy, in order to keep the “Peace at home, peace in the world” principle in this period.

The National Pact, aiming at establishing a Turkish nation state in areas of the former Ottoman Empire where Turks are majority has been realized with the end of the Independence War and this has got an international recognition through Lausanne Peace Treaty.[3] This has formed the basic Turkish foreign policy principle: defending the status quo established by this international treaty. That’s why Turkish foreign policy has been considered as “cautious”, in other words as being away from adventure and maintaining passive role.

First years of the new republic, meaning the 1920s, have been full of efforts to resolve the issues that have not been fully closed by the Lausanne Peace Treaty. The first issue to deal with was the Mosul case.[4] Following the Lausanne Treaty in July 1923, Turkey and Britain have realized unsuccessful negotiations between May and June 1924. Then, bilateral negotiations were restarted in Ankara in April 1926, and an agreement was signed on June 5th, 1926. This agreement prepared the ground for a rapprochement with Great Britain and other Western powers. Another important issue was the population exchange between Turkey and Greece. This exchange has created complicated disputes over the disposition of properties remained in the each country by the emigrants. The issue was finally resolved with an agreement between Turkey and Greece in June 1930.

One of main principles of Turkish foreign policy in this period was to have good relations and develop cooperation with the Soviet Union. This doesn’t mean that Turkey was an ally of this country, but Turkey has at least tried to make sure not to oppose this country. In the inter-war period, the main threat perception of Turkey was from Italy. Turkey has also taken some initiatives in order to build alliances and partnerships, namely joining the League of Nations in 1932, the formation of the Balkan Pact with Greece, Romania and Yugoslavia in 1934, the signing of Montreux Straits Treaty in 1936, the formation of Saadabad Pact with Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan in 1937 and the signing of Tripartite Alignment Treaty with Britain and France in 1939 against the Soviet Union.

1.2 Turkish Foreign Policy during the Cold War Era

From 1939 to 1945, which means during Second World War, Turkey has remained neutral until almost the end of this devastating conflict and joined the United Nations as a founding member. In the post-WWII period, the globe has plunged into a bipolar system, based on the rivalry of two super powers, namely the US and the Soviet Union. Turkey has decided to join in the Western bloc and its institutional structures (Council of Europe in 1949, NATO in 1952). Turkey has acted in harmony with the United States during the Cold War period, and has endeavored to align her both domestic and foreign policies largely with NATO and Europe.[5] The reasons of this orientation can be displayed as Turkey’s economic needs during the Cold War period, threats emanating from the USSR, the Truman Doctrine (1947) and its need of military aid as shown by the Marshall Plan in 1948.

At the practical level, Turkey’s NATO membership provided the ground for a close relationship with the United States.[6] This has also helped Turkey to take a new position inside Europe. After centuries of being viewed as “barbarians at the gates”, the Turkish army got the role of “gatekeeper”, defending Europe’s southern flank against the Soviet threat. After becoming a NATO member, Ankara started to follow one-dimensional foreign policy evaluating all international events through the glasses of Washington. In order to secure its place within the Western bloc,Turkey has even sent soldiers to the Korean War.

In the same period, the application of Turkey to EEC in 1959 and Association Agreement in 1963 that targets full membership are evaluated as the efforts put forward by Ankara for integrating every western institution.[7] Europe was generally more critical towards Turkey because of its lack of democracy than the US, but the latter too, at least as a principle, supported this intention. In the mid-1960s, Turkey has not found enough support for the resolution of the Cyprus problem neither from the United Nations nor Western Europe. The challenges faced following Turkey’s military intervention in Cyprus and the arms embargo that has followed has caused the doubts on the thought of Turkey as being a part of European Community. Turkey’s reaction to this loneliness in the international arena has been to develop relations with the USSR and East and Muslim world by not abandoning her obligations in the Western bloc under the heading of multidimensional foreign policy.

Given the internal security chaos in the 1970s, Turkey has distanced itself from the West.[8] However, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the coming into power of Khomeini administration in Iran both in 1979 and the breaking out of Iran-Iraq War in September 1980 has further increased the importance of Turkey in the eyes of Washington.

1.3 Turkish Foreign Policy towards the 21st century

After the September 12th, 1980 coup, the first democratic elections were held in 1983 under the new constitution adopted by referendum in 1982.[9] Voters demonstrated their will by giving the majority to one party which was considered as more independent from the military establishment: Turgut Özal’s Motherland Party. Turkey was really in need of political leaders with vision. As Prime Minister (1983-1989), then President (1989-1993), Turgut Özal demonstrated that he had this vision. Combining economic liberalism and Islamic values, he affected Turkish foreign policy almost more radically than anyone since Atatürk.

In this period, Özal has been the most influential figure in Turkey’s foreign policy making.[10] Özal’s refusal of static and traditional structures and his wish to change totally the functioning of the state in domestic and in international arena, is an important factor that also explains his personal style, based on underestimating the strict rules of ministry of foreign affairs. His international career, as he has also worked in international organizations, besides his personal contacts with many foreign statesmen in the eastern and western world are probably the reasons that explain his active foreign policy participation.

In the post-Cold War era, both in Turkey and abroad, the new international situation was quite unprecedented, arousing a debate about Turkey’s future international role. The end of the Soviet threat had decreased Turkey’s international influence, because Ankara’s role as cornerstone of Western security in the eastern Mediterranean had now disappeared.[11] Turkey might be viewed as a strategic and political liability rather than an asset to the Western strategy as it did have a long list of complex regional security concerns. Its EU candidacy, the Kurdish problem, its poor human rights record, and many conflicts with Greece have marked the first years following the end of the Cold War. Turkey has insisted to present itself as a bridge between Europe and the Middle East and Central Asia, but there was a danger that Western Europe might prefer to view it as a barrier against a hostile other, left outside European structures.

Turkey’s main foreign policy orientation has continued to be US- and NATO-centric in the post-Cold War era. When the international system was undergoing a change and evolving into a unipolar structure, Turkey has faced many difficulties in the face of this new international system as it was quite unprepared to such a major transformation. Ankara has made important initiatives within the context of her power, diplomatic experience and with conjuncture. Especially, she has recognized the republics emerged out of with the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the USSR.

After the PKK has launched its terrorist campaign in mid-1980s and the Gulf War, Iraq has been one of the most significant issues of Turkish foreign policy.[12] After the dissolution of the USSR, Turkey has strengthened her relations with the other countries in Central Asian Republics and Black Sea. In the aftermath of Gulf War in 1991, according to Özal, Turkey would follow an active foreign policy instead of her old passive and hesitant policies. Seeing the Turkey’s interest in European integration as an important value for the development of economy and democracy, he has envisaged the very long term effects of opening abroad. Moreover, Özal and his top assistants have made important efforts for Turkey’s being as the leader of Muslim world by the reasoning of further making progress of Muslim communities through Turkish Islam.

In 1987, Turkey applied for full membership to the European Community. Although the application was rejected in 1989 by the European Commission, the door for Turkey was remained open, as the Commission in its 1989 Opinion verified Turkey’s eligibility for membership.[13] Brussels has developed the enlargement policy toward the Central and Eastern European countries that broke up from the Eastern Bloc in the beginnings of 1990s. Turkey has been kept out of this process with the 1997 Luxembourg Summit and eight Central and Eastern European countries as well as two Mediterranean countries became the members of the EU in 2004. Turkey was declared as a candidate for full membership in 1999 Helsinki Summit.

2. Main Dynamics in Turkish Foreign Policy in the 2000s.

The congress of Fazilet (Virtue) Party on May 17, 2000 was a great historical moment in the history of Islamic parties in Turkey given the existence, for the first time, of an open contest for the party leadership.[14] The modernist wing has declared Abdullah Gül as their candidate against the incumbent leader Recai Kutan, supported by Necmettin Erbakan. Gül received 521 votes and Kutan 633. Such a close competition was a precursor of unstoppable division within the Virtue Party.

A suitable condition emerged with the ban of Virtue Party by the Constitutional Courton July 22nd, 2001.[15] When the traditionalists established the Saadet (Felicity) Party, the modernists founded the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) on August 14th, 2001. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was chosen as the leader of party with consent. In general elections held on November 3rd, 2002, AK Party won 34, 3% of the votes and 66% of the seats in Turkish Grand National Assembly. Now,Turkey got a single-party government for the first time since the Motherland Party lost its majority in 1991.

Although there adduced some objections and concerns on AK Party, there are two reasons of why the forces in the center of the state did not intervene toward the AK Party government.[16] The first one is the AK Party’s getting the majority in Turkish Grand National Assembly as a result of the general elections and the offering of AK Party as a non-alternative government option. Given the impossibility of forming a single-party government by Republican People’s Party, another party in the assembly, the prevention of formation of the government by the AK Party could have further deepened the ongoing economic, political and even security crisis experienced in Turkey. The echoing of deep economic, social, and political crises ofTurkey in 1990s and especially in 2001 was a condition neither undergone nor faced by the state forces in Turkey and the international actors.

In terms of domestic and foreign policy, AK Party officials have declared that they do not have any target or approach that would violate the basic principles or traditions of Turkish foreign policy. Regarding secularism, as the most fundamental feature of the state and a test case for the AK Party, they have declared that they share the traditional thoughts and the central approach.[17]

In the international arena, the most important developments in this period were the 9/11 terror attacks against the United States, and then the latter’s occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq.[18] The central feature of all these developments is Washington’s effort to transform the region including Turkey by changing the regimes within the context of her unilateral foreign policy view. This period is also marked by a rising anti-Americanism in Europe and the Muslim world.

2.1 AK Party’s Foreign Policy Perspective

Prof. Dr. Ahmet Davutoğlu, ex-chief foreign policy advisor of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, is the ideologue of AK Party’s foreign policy.[19] He wrote a book entitled “Strategic Depth: The International Position of Turkey”, published in April 2001. According to Davutoğlu, there has been some fundamental foreign policy principles followed by Turkey in a consistent manner, namely respecting territorial integrity of all states, resolution of problems through reconciliation and dialogue, remaining within the Western alliance, through NATO membership and the EU accession process. These fundamental principles are also valid in the new era but the new principles and viewpoints have to be developed in the aftermath of Cold War period.

Davutoğlu claims that he is a prudent realist.[20] Erhan states that “Davudism” is an ideological design that searches beyond the Ottoman territories and alleges to be global. The theoretical background of Davutoğlu’s foreign policy approach presents a synthesis of four fundamental factors. Here, as being dependent on conjuncture, one of these factors forestalls another factor and the dimension among them is not important. The first main factor is idealism which is inspired by Immanuel Kant’s thoughts on international relations. Davutoğlu underscores that there exist valid ethical values for every actor of the international relations. Just as in the daily social relations between real persons, states should act in an honest and just manner.

The second factor is diachronicism in which it is a methodological approach limited with historical-cultural references utilized by Davutoğlu in explaining the global relations and Turkish foreign policy.[21] He alleges that Turkey has not used the advantages provided by the Ottoman heritage in the foreign policy followed by Turkey since the establishment of the Republic and thus Turkey has been in a dilemma with how to deal with regional developments emerging in the aftermath of Cold War. In this context, Davutoğlu views the formation of a sphere of influence in the former Ottoman geography by Turkey.

The third factor is geopolitical attitude. By merging the classical geopolitical terms with cultural objects, Davutoğlu mentions that a new geoculture is emerging in the Islamic world. The main feature of this geoculture is pluralism within the unity.[22] The unifying factor of the Muslim world is the awakening of a civilization as a response to modernization and its universal variables. According to Davutoğlu, when you draw a line from Germany, France, and Italy to Russia in the north,China and India in the East, the most powerful economy in the region which stays in between is Turkey. Ankara cannot turn a blind eye to any problem in her region. The “World Island” is seen by Davutoğlu as lying from China to North Africa which is “Traditional/Geopolitical Order.” Davutoğlu’s Heartland is Balkans-Caucasia-Middle East Triangle. He thinks that if Turkey manages to constitute an order in this region, it will be influential in the global level as well.

The last foundational factor is the integration models. Davutoğlu considers the likelihood of Ankara’s integration with neighboring countries and regions.[23] He notices that the abolishment of economic boundaries among countries which are situated in the same geography and which have cultural affinities will, for a while, be able to bring a very powerful political cooperation provided that the process is managed well. Here it can be said that the integration model of Davutoğlu’s foreign policy approach is under the influence of two important integration theories, namely Ernst Haas’s Neo-Functionalism and Karl Deutsch’s Security Communities.

To Davutoğlu, Ankara acquires the capability and the responsibility to pursue an integrated and multidimensional foreign policy given it has multi-regional identities.[24] The matchless mixture of Turkey’s history and geography necessitates this responsibility for Ankara. Contributing actively towards conflict resolution and international peace and security in all these areas, is a call of duty emerging from the depths of a multidimensional history for Turkey.

To Davutoğlu, the first pillar of the multifaceted platform of Ankara’s foreign policy is the indivisibility of security.[25] Security should not be regarded as a zero-sum game whereby the safety of “country A” can be developed at the expense of the well-being of “country B”. He thinks that dealing with an environment of instabilities created by micro ethnic fluctuations in the whole world today poses a great question. The only way to prevent the bringing of identity differences which makes the coexistence impossible passes from the formation of “freedom-security balance.” According to Davutoğlu; a Turkey which can establish a freedom-stability balance well, will be able to resolve her problem and present a model for the world.

Another pillar is the concept of dialogue. He thinks that Turkey should not evaluate any opposing country party as fundamentally evil.[26] Whereby, the most important events of the international arena are happening in a region which Turkey can influence and all these developments have a direct impact on Turkey. To Davutoğlu, here, Ankara’s concurrent foreign policy method is the dialogue and diplomacy. This is summarized by the “zero problem with neighbors” slogan.

Davutoğlu alleges that Turkey is a pivotal country.[27] Davutoğlu underlines that Turkey should be a pro-active country by proposing concrete solutions. Turkey should be free from its complexes, and should not be ashamed from its Eastern identity. It should act as an Eastern country in eastern platforms and as a Western country in western platforms. It should become a country that can discuss Europe’s future as an equal partner with major European powers. Thus, of the main principles of the new Turkish foreign policy is not to become estranged to the region.

2.2 Clues for Turkish Foreign Policy of the 2010s

Turkey is concurrently the only country that is simultaneously a member of the Council of Europe, NATO, OECD, G-20 and Islamic Cooperation Organization. In recent years, Turkey has played the role of mediator, conciliator, and arbitrator. According to Stephen Kinzer, the world urgently needs countries to fulfill this kind of roles. Few countries are better equipped to play this role than Turkey.[28] When Israel desired to start secret talks with Syria, it called out Turkey to arrange them. After Sunnis in Iraq made the decision to boycott the elections, Turkey convinced them to change their minds and participate. Whenever Turkish officials go in a bitterly divided country like Lebanon or Pakistan, every faction is willing to talk to them. Ankara is trying to calm tensions between Iran and the United States, between Syria and Iraq, between Armenia and Azerbaijan. No countries’ diplomats are equally welcome in Tehran and Washington, Moscow and Tblisi, Damascus and Cairo. No other nation is shown respect by Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Taliban while carrying out good ties with the Israeli, Lebanese, and Afghan governments.

But some events in recent years about the Turkish foreign policy are regarded by some Westerners as an “Axis Shift.” For instance, the differences between Washington and Ankara over the Iraq war came into forefront in early 2003, when Turkey was under the pressure to respond to a U.S. demand to preposition the Fourth Armored Division in Turkey for a potential invasion of Iraq from the north.[29] The talks resulted with a U.S. offer to provide Turkey with a $6 billion assistance package that could be leveraged to back up $24 billion loan in guarantees, in return Turkey accepted the grant the American military access to its territory for staging purposes. But on March 1, 2003, the motion did not get the required majority of votes cast in the Turkish Grand National Assembly (267 of the 533 votes cast) and failed.

Another incident over the Iraq war has worsened the relations between Washington and Ankara on July 4th, 2003, when the U.S. armed forces in northern Iraq detained eleven Turkish Special Forces commandos suspected of planning to participate in the assassination of a local Kurdish politician. Turkish officers got released after forty-eight hours, but not before they were photographed hooded and behaved as prisoners by the Americans, resulting in great humiliation and resentment in Turkey.[30]

In the same period, Turkey has grown more critical toward Israel with every passing day. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been criticizing the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians and has been backing the involvement of Hamas in peace talks.[31] In February 2006, Turkey has been the first country to host the exiled leader of Hamas, Khaled Meshaal in an unofficial visit. American Jewish Committee has reviewed this visit as “a tragic mistake that would have serious repercussions not only among the governments of Western democracies but the Jewish community in the United States and around the world and with those friends of Turkey”. Former American Department of State official Henri J. Barkey, in his article stated the following remarks on this issue; “WASHINGTON, Jerusalem and Brussels were shocked when the Turkish government recently invited the leader of Hamas, Khaled Meshaal, to Ankara. By hosting the leader of a terrorist organization — one that has taken terror to new heights with its suicide bombings of malls and city buses — Turkey undermined its own cause. After all, Turkey has for many years been campaigning to get its homegrown Kurdish insurgency classified as a terrorist group. The United States and European Union have done so. So the invitation to the Hamas leader was particularly strange coming from Turkey, even while Turkey is negotiating to join the EU”.[32]

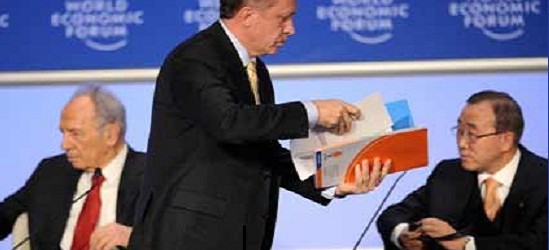

Between 2007 and 2008, Turkey has played a mediatory role in peace negotiations between Israel and Syria. But these negotiations were made null by Israel’s Operation Cast Lead on December 27, 2008 against Gaza Strip.[33] Ankara has strongly reacted given the occurrence of this operation after a very short time after Israel’s Prime Minister Ehud Olmert visited Ankara. After that, the peace process has stopped between Israel and Syria. In early 2009, Erdoğan caused another distraction with tough walk against Israel in Brussels and a walk-off from the stage in the World Economic Forum in Davos known as “One Minute Crisis”. In both of these places, he endeavored to concentrate world condemnation on Israel actions in Gaza, but instead European and American audiences concentrated on whether the forthright style in which he proved his Islamic root or that Turkey was leaving from the West.

At the end of 2009, another shock for Tel-Aviv was the abolishment of Anatolian Eagle air force drill’s international division in which one of the participants of was Israel by Turkey.[34] On January 12th, 2010, “Low Seat Crisis” occurred between Turkey and Israel. In a meeting between Vice Foreign Affairs Minister Danny Ayalon and Turkey’s ambassador to Tel Aviv, Oğuz Çelikkol, Ayalon did not shake the hands of Mr. Çelikkol and gave him a lower seat. After this event, Turkey called his ambassador in Tel-Aviv back. On May 31st, 2010, another great crisis happened between Turkey and Israel. An international aid flotilla led by Humanitarian Aid Foundation (IHH) trying to get attention the embargo in Gaza was stopped by Israeli army in the international waters.[35] The Israeli army harshly intervened in the Mavi Marmara ship and killed 9 citizens and wounded 24 people. Turkey has been demanding an apology from Turkey before the public opinion, the acceptance of an independent investigation on the attacks toward the ships and the end of blockade in Gaza from Israel.

Ankara finds Iran’s possible acquisition of nuclear weapons dangerous within the context of regional stability and does not desire it.[36] Turkey’s approach and Israel’s approach to the Iran’s policy of acquiring nuclear weapons is completely different. When Israel seriously keeps the option of bombing the nuclear facilities of Iran, Turkey thinks that Iran, as a legitimate actor, should be included in international system. As one of the signatories of Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Iran should have the right to nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. According to another view proposed by Turkey is that the real peace and stability in the region will only be possible with the abolishment of all weapons of mass destruction in the region. While Israel possesses nuclear weapons, harsh criticism and punishment of only Iran because it is following the same objective would never be a totally ethical approach.

Turkey is in favor of a solution of the nuclear energy problem of Iran in peaceful and diplomatic ways. In that regard, Abdullah Gül, ex-foreign minister and now president of Turkey, has paid a visit to Tehran in June 2006 and talked with the secretary of Supreme National Council of Iran, Ali Larijani, about Turkey’s mediation.[37] He offered the hosting of talks between Iran and EU’s High Representative of Foreign Affairs in Ankara. Larijani accepted the offer. The Solana-Larijani meeting was made in Ankara on April 25-26, 2007. The meeting has paved the way for a technical agreement between Iran and IAEA in August 2007. This meeting has been the first and up to now the last regional attempt to deal with Iran’s nuclear activities. The reasons why Iranians have accepted Turkey’s offer for mediation between them and the West on the nuclear issue are as the following;

- Iran’s relative trust in Turkey and especially in its trust in the AKP.

- Turkey has repeatedly recognized Iran’s importance in the region and has not denied its stabilizing role.

- Iran perceives Turkey as more independent when compared to other regional states, even including other US regional allies.

- It seems that the Iranian leaders have decided to expand ties with Turkey beyond the issues of PKK and Kurdish question.

On May 17, 2010, with Turkey’s initiative and her intensive diplomacy, Turkey, Brazil and Iran have signed the “Nuclear Swap Deal” in Tehran. This deal has attracted the attention of world public opinion. In previous months, Iran had rejected the P5 +1’s offer by alleging the lack of necessary condition for trust. In this agreement, the parties have agreed upon the exchange of low-enriched nuclear fuel with the 20 % enriched nuclear fuel to be used in reactors.[38] With her developing industry and economy at present, Turkey intensively faces with the energy need. From the perspective of Turkey, because it is ascending to the leading role among her eastern neighbors within the context of energy production and exportation, the development of relationships with these countries is vital. In this perspective, Turkey has to be in a condition of taking initiatives timely and following the developments about every kind of regional and international subjects on Iran closely. Finally, the reason behind the final step taken with the Tehran agreement is that Turkey sees the maintenance of peace, stability, and security in her region crucial for the protection of her own national interests.

It would be good to give the view of Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prof. Dr. Ahmet Davutoğlu, on the nuclear program of Iran. He states that “You cannot say that the nuclear technology is mine and that technology can only be used by a group of states. You cannot deprive any state of her rights by declaring any state as an absolute suspicious. At that time, there is no such thing as international law”.

Another dimension of the issue of Iranian nuclear program is the opening of the legitimacy of international law into discussion.[39] Together with Turkey, Iran has started to develop a critical outlook on questioning international law and the functionality of the United Nations. In most of his speeches, Ahmadinejad has firstly stated the acquisition of nuclear weapons by Israel being non-party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and stated that “First hold responsible to Israel, then let’s talk”. Prime Minister of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has mentioned that Israel has nuclear weapons and the countries which criticize Iran firstly have to hold responsible Tel-Aviv.

Another important crisis area in this period is the relations between Ankara and Brussels. On October 3rd, 2005, Turkey started to make full membership negotiations with the EU. Until now, 13 chapters were opened and only one of them was provisionally closed. Given Cyprus issue and France’s blockade on the opening of some chapters, the relations are now about to freeze.[40] The current problems regarding Turkey’s EU candidacy is also occasionally utilized as a means of criticism of the AK Party governments and is often claimed that AK Party is not very enthusiastic on the issue of Turkey’s membership given its Islamic nature. It would be correct to state that the Turkey’s EU membership process is not at the condition that it should normally be. The general enlargement fatigue of the EU, the Cyprus problem, and the rising anti-Turkish rhetoric from France and Germany’s influential political leaders are influential factors in this recent stalemate. It could be alleged that a setback in relations is less related to Turkey’s multidimensional choices of foreign policy.

Conclusion

The Turkish foreign policy which was built upon Westernism, Conservatism and status quo principles since the Atatürk period has gone through a necessary change with the emergence of several potential threats in the aftermath of Cold War. In this period, Turkish foreign policy has gone into a different structure and new conditions have pushed Turkey to take strong interest in her region and to follow a more active policy.

Together with the changing conjuncture after September 11 attacks, Turkey has launched a new policy orientation. This change has become more apparent with the AK Party government from 2002 on and the appointment of Ahmet Davutoğlu as Minister of Foreign Affairs in 2009. Defining a foreign policy that is proactive, progressive and intended for international relations, Davutoğlu advocates that soft power is Turkey’s main source. Turkey will also rise into a country that realizes the geopolitical, geocultural and geoeconomic integration provided that she forms a unity between her history and geographical depth.

Consequently, Turkey has been in the process of being an influential actor in her region by making changes in her recent diplomacy approach. In this point, AK Party government underlines that this new foreign policy approach does not mean the total break up from the Western alliance. AK Party advocates that they try to develop a new international relations approach for Turkey by accentuating the East policy as well as West policy. Some experts mention that the development of Ankara’s alignment vision with neighboring countries is a natural result of the international relations.

The axis shift is defined as Turkey’s strengthening of her bonds with the East by breaking up her bonds with the West. Here, the following questions should be asked: did Turkey leave from NATO, Council of Europe, did it suspend the negotiations with the EU, did it leave from the OSCE, did it break up all relations with Washington, did she leave from Alliance of Civilizations, did she abandon the principles of democracy, human rights, fundamental rights and liberties, rule of law and secularism. If all of these things happen, it might be said that there is an axis shift.

Davutoğlu has been successful in forming a conceptual strategy for Turkish foreign policy with a new understanding. Time will show better that how these policies and strategies of Davutoğlu those seem concrete in theory will be successful in practice.

Sina KISACIK

REFERENCES

Ahmad, Feroz. Bir Kimlik Peşinde Türkiye. Translated by Sedat Cem Karadeli. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2006.

Akyol, Taha. Tarihin Dönüşü.İstanbul: Yakın Plan Yayınları, 2010.

Arı, Tayyar. Liderler, Kanaat Önderleri ve Kamuoyunun Gözünden Yükselen Güç: Türkiye-ABD İlişkileri ve Ortadoğu. Bursa: MKM Yayıncılık, 2010.

Aras, Bülent. “Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy”, SETA. May 2009, accessed December 20, 2011, http://www.setav.org/Ups/dosya/7710.pdf.

Barkey, Henri J. “Two-faced on terrorism”, Los Angeles Times. 11 March 2006, accessed on November 22, 2011, http://articles.latimes.com/2006/mar/11/opinion/oe-barkey11.

Bonab, Rahman G., “Turkey’s Emerging Role as a Mediator on Iran’s Nuclear Activities”, Insight Turkey 11, No.3, (2009): 161-175.

Danforth, Nicholas. “Ideology and Pragmatism in Turkish Foreign Policy: From Atatürk to the AKP”, Turkish Policy Quarterly 7, no.3, Fall 2008: 83-95.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet. Stratejik Derinlik: Türkiye’nin Uluslararası Konumu, 24th edition.İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2008.

Düzgit, Senem Aydın and Nathalie Tocci. “Transforming Turkish Foreign Policy: The Quest for Regional Leadership and Europanisation’, CEPS. November 13, 2009, accessed on December 1, 2011, http://www.ceps.be/book/transforming-turkish-foreign-policy-quest-regional-leadership-and-europeanisation.

Erhan, Çağrı. Türk Dış Politikasının Güncel Sorunları. Ankara: İmaj Kitabevi, 2010.

Fuller, Graham Edmund. The New Turkish Republic: Turkey As A Pivotal State In The Muslim World. Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2008.

Findley, Carter Vaughn. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History. London: Yale University Press, 2010.

Gözen, Ramazan. İmparatorluktan Küresel Aktörlüğe Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası.Ankara: Palme Yayıncılık, 2009.

Gözen, Ramazan, “Türk Dış Politikasında Değişim Var Mı?”, in Türkiye’nin Değişen Dış Politikası, edited by Cüneyt Yenigün and Ertan Efegil, 19-37. Ankara: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım, 2010.

Gordon, Philip H. and Taşpınar, Ömer. Winning Turkey: How America, Europe, and Turkey Can Revive A Fading Partnership.Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2008.

Hale, William. Turkish Foreign Policy: 1774-2000. London: Frank Cass, 2002.

Karabulut, Bilal. “Alçak Koltuk Krizi”, in Türk Dış Politikasında 41 Kriz: 1924-2012, edited by Haydar Çakmak, 375-383.Ankara: Kripto Basım Yayım, 2012.

Keneş, Bülent. İran: Tehdit mi, Fırsat mı?. İstanbul: Timaş Yayınları, 2012.

Kibaroğlu, Mustafa, and Ayşegül Kibaroğlu. Global Security Watch: Turkey, A Reference Handbook. United States of America: Praeger Security International, 2009.

Kinzer, Stephen. Reset: Iran, Turkey, and America’s Future. New York: Times Books, 2010.

Koçer, Gökhan. “AKP’nin ve Tayyip Erdoğan’ın Dış Politika Felsefesi”, in Türk Dış Politikası: 1919-2008, edited by Haydar Çakmak, 920-927. Ankara: Barış Platin Kitap, 2008.

Küntay, Burak. Major Shift: The Change in U.S. Foreign Policy During the 2003 Iraq War Era and Turkish-U.S. Relations. İstanbul: Bahçeşehir University Press, 2011.

Laçiner, Sedat. “Yeni Dönemde Türk Dış Politikasının Felsefesi, Fikri Altyapısı ve Fikirleri”, in Yeni Dönemde Türk Dış Politikası: Uluslararası IV. Türk Dış Politikası Sempozyumu Tebliğleri, edited by Osman Bahadır Dinçer, Habibe Özdal and Hacali Necefoğlu, 3-47.Ankara: USAK Yayınları, 2010.

Özbudun, Ergun and William Hale. Türkiye’de İslamcılık, Demokrasi ve Liberalizm: AKP Olayı. Translated by Ergun Özbudun and Kadriye Göksel. İstanbul: Doğan Kitap, 2010.

Özhan, Taha. “Turkey, Israel and the US in the Wake of the Gaza Flotilla Crisis.”, Insight Turkey 12, no. 3, (2010) : 7-18.

Özcan, Mesut, Usul, Ali Resul. “Understanding the “New” Turkish Foreign Policy: Changes within Continuity, Is Turkey Departing From The West?”, Uluslararası Hukuk & Politika: Review of International Law & Politics 6, no. 21, 2010: 101-123.

Özgöker, Uğur, and Sezin İba. “Uluslararası İlişkiler ve Türkiye’nin Yeni Dış Politikası”, in 21. Yüzyılda Çağdaş Türk Dış Politikası ve Diplomasisi, edited by Hasret Çomak, 79-103. Kocaeli: Umuttepe Yayınları, 2010.

Park, Bill. Modern Turkey: People, State and Foreign Policy in a Globalized World. London: Routledge, 2012.

Sanberk, Özdem. “Türk Dış Politikasının Dönüşümü: Öncelikler Nelerdir? Rota Değişikliği Var mı? , in 21. Yüzyılda Çağdaş Türk Dış Politikası ve Diplomasisi, edited by Hasret Çomak, 103-113. Kocaeli: Umuttepe Yayınları, 2010.

Sandıklı, Atilla. “Jeopolitik Teoriler ve Türkiye”, in Dünya Jeopolitiğinde Türkiye, edited by Hasret Çomak, 345-371. İstanbul: Hiperlink Yayınları, 2011.

Tocci, Nathalie. Turkey’s European Future: Behind The Scenes of America’s Influence on EU-Turkey Relations.New York:New YorkUniversity Press, 2011.

Zengin, Gürkan. Hoca: Türk Dış Politikasında “Davutoğlu Etkisi”. İstanbul: İnkilap Kitabevi, 2010.

[1] Ramazan Gözen, “Türk Dış Politikasında Değişim Var mı?”, in Türkiye’nin Değişen Dış Politikası, eds. Cüneyt Yenigün and Ertan Efegil (Ankara: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım, 2010), p. 22.

[2] Özdem Sanberk, “Türk Dış Politikasının Dönüşümü: Öncelikler Nelerdir? Rota Değişikliği Var mı?”, in 21. Yüzyılda Çağdaş Türk Dış Politikası ve Diplomasisi, ed. Hasret Çomak (Kocaeli: Umuttepe Yayınları, 2010), p. 103.

[3] Faruk Sönmezoğlu, İki Savaş Sırası ve Arasında Türk Dış Politikası, (İstanbul: Der Yayınları, 2011), p.254.

[4] William Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy: 1774-2000, (London: Frank Cass, 2002), pp. 58-59.

[5] Uğur Özgöker and Selin İba, “Uluslararası İlişkiler ve Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası”, in 21. Yüzyılda Çağdaş Türk Dış Politikası ve Diplomasisi, ed. Hasret Çomak (Kocaeli: Umuttepe Yayınları, 2010), p. 84.

[6] Nicholas Danforth, “Ideology and Pragmatism in Turkish Foreign Policy: From Atatürk to the AKP”, Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 3, (2008), p. 87.

[7] Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy: 1774-2000, pp. 156-157.

[8] Feroz Ahmad, Bir Kimlik Peşinde Türkiye, trans. Sedat Cem Karadeli, (İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, 2006), p. 179.

[9] Carter Vaughn Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, (London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 354.

[10] Ramazan Gözen, İmparatorluktan Küresel Aktörlüğe Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası, (Ankara: Palme Yayıncılık, 2009), p. 75.

[11] Hale, Turkish Foreign Policy: 1774-2000, pp. 192-193.

[12] Bill Park, Modern Turkey: People, State and Foreign Policy in a Globalized World, (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 104-105.

[13] Nathalie Tocci, Turkey’s European Future: Behind the Scenes of America’s Influence on EU-Turkey Relations, (New York: New York University Press, 2011), pp. 2-4.

[14] Ergun Özbudun & William Hale, Türkiye’de İslamcılık, Demokrasi ve Liberalizm: AKP Olayı, trans. Ergun Özbudun and Kadriye Göksel, (İstanbul: Doğan Kitap, 2010), p. 55.

[15] Findley, Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, p. 359.

[16] Gözen, İmparatorluktan Küresel Aktörlüğe Türkiye’nin Dış Politikası, p. 112.

[17] Graham Edmund Fuller, The New Turkish Republic: Turkey As A Pivotal State In The Muslim World, (Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2008), p. 50.

[18] Mustafa Kibaroğlu and Ayşegül Kibaroğlu, Global Security Watch: Turkey, A Reference Handbook, (United States of America: Praeger Security International, 2009), p. 111.

[19] Gürkan Zengin, Hoca: Türk Dış Politikasında “Davutoğlu Etkisi”, (İstanbul: İnkilap Kitabevi, 2010), p. 84.

[20] Çağrı Erhan, Türk Dış Politikasının Güncel Sorunları, (Ankara: İmaj Kitabevi, 2010), p. 3.

[21] Ahmet Davutoğlu, Stratejik Derinlik: Türkiye’nin Uluslararası Konumu (İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2008), pp. 73-74.

[22] Atilla Sandıklı, “Jeopolitik Teoriler ve Türkiye”, in Dünya Jeopolitiğinde Türkiye, ed. Hasret Çomak ( İstanbul: Hiperlink Yayınları, 2011), pp. 362-364.

[23] Sedat Laçiner, “Yeni Dönemde Türk Dış Politikasının Felsefesi, Fikri Altyapısı ve Hedefleri”, in Yeni Dönemde Türk Dış Politikası: Uluslararası IV. Türk Dış Politikası Sempozyumu Tebliğleri, eds. Osman Bahadır Dinçer, Habibe Özdal, Hacali Necefoğlu, (Ankara: USAK Yayınları, 2010), p. 17.

[24] Bülent Aras, “Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy”, SETA Policy Brief, No.32, pp. 7-8. Available online at http://www.setav.org/Ups/dosya/7710.pdf (accessed on 20.12.2011).

[25] Gökhan Koçer, “AKP’nin ve Tayyip Erdoğan’ın Dış Politika Felsefesi”, in Türk Dış Politikası: 1919-2008, ed. Haydar Çakmak (Ankara: Barış Platin Kitap, 2008), p. 922.

[26] Taha Akyol, Tarihin Dönüşü, (İstanbul, Yakın Plan Yayınları, 2010), pp. 92-93.

[27] Zengin, Hoca: Türk Dış Politikasında “Davutoğlu Etkisi”, pp. 91-92.

[28] Stephen Kinzer, Reset: Iran, Turkey, and America’s Future, (New York: Times Books, 2010), pp. 196-197.

[29] Philip H. Gordon and Ömer Taşpınar, Winning Turkey: How America, Europe, and Turkey Can Revive A Fading Partnership, (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2008), pp. 30-32.

[30] Burak Küntay, Major Shift: The Change in U.S. Foreign Policy during the 2003 Iraq War Era and Turkish-U.S. Relations, (İstanbul: Bahçeşehir University Press, 2011), pp. 170-172.

[31] Gordon and Taşpınar, Winning Turkey: How America, Europe, and Turkey Can Revive A Fading Partnership, p. 33.

[32] Henri J. Barkey, ‘Two-faced on terrorism’, Los Angeles Times, 11 March 2006. Available online at http://articles.latimes.com/2006/mar/11/opinion/oe-barkey11 (accessed on 11.11.2011).

[33] Senem Aydın Düzgit and Nathalie Tocci, ‘Transforming Turkish Foreign Policy: The Quest for Regional Leadership and Europanisation’, CEPS Commentary, 2. Available online at http://www.ceps.be/book/transforming-turkish-foreign-policy-quest-regional-leadership-and-europeanisation (accessed on 01.12.2011).

[34] Bilal Karabulut, “Alçak Koltuk Krizi”, in Türk Dış Politikasında 41 Kriz: 1924-2012, ed. Haydar Çakmak (Ankara: Kripto Basım Yayım, 2012), pp. 377-379.

[35] Taha Özhan, “Turkey, Israel and the US in the Wake of the Gaza Flotilla Crisis”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 12, No.3, (2010), p. 8.

[36] Tayyar Arı, Liderler, Kanaat Önderleri ve Kamuoyunun Gözünden Yükselen Güç: Türkiye-ABD İlişkileri ve Ortadoğu, (Bursa, MKM Yayıncılık, 2010), p. 110.

[37] Rahman G. Bonab. “Turkey’s Emerging Role as a Mediator on Iran’s Nuclear Activities”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 11, No.3, 2009, p. 170.

[38] Bülent Keneş, İran: Tehdit mi, Fırsat mı?, (İstanbul: Timaş Yayınları, 2012), pp. 342-343.

[39] Keneş, İran: Tehdit mi, Fırsat mı?, pp. 308-309.

[40] Mesut Özcan, Ali Resul Usul, “Understanding the ‘New’ Turkish Foreign Policy: Changes within Continuity, Is Turkey Departing From The West?”, Uluslararası Hukuk & Politika: Review of International Law & Politics Vol.6, No. 21, (2010), p. 106.

One Comment »