In 2011, Turkey’s second largest trading partner was the Russian Federation ($30 billion; $6 billion exports, $24 billion imports and the fundamental good in mutual trade was energy – 70 percent of imports; $21 billion).[1] Naturally, collaboration and trade in the energy field with Moscow forms one of the fundamental factors of Ankara’s multidimensional bilateral relations. As economic collaboration is one of the components driving political relations, the close collaboration Ankara has constituted with Moscow is not only seen in the trade numbers, but has also been influential in further deepening of affiliations in the political arena by forming a mutual economic interdependence (more on energy supply dependency to Turkey).

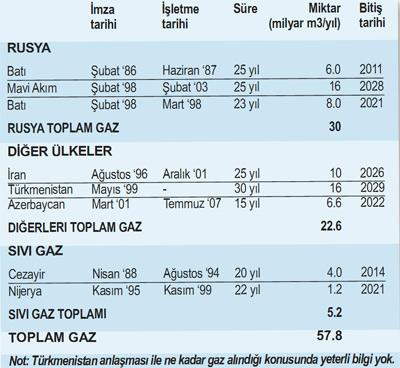

Though economic connections between the countries have been getting much closer in recent years, their relations in the energy sector are not a new phenomenon. In 1984, NATO member Turkey put signature a 25 year natural gas purchase agreement with the Soviet Union.[2] Although at that time this agreement was relatively advantageous to Ankara with regard to prices, it also did pave the way for energy dependency that has only increased in the following years. Furthermore, the initially promising gas prices stimulated Ankara to strongly grip natural gas a source of electricity: around %50 of Turkish electricity is generated from gas and %55 of Turkish gas are used for producing electricity. This is a costly particularity making Ankara all the more dependent on its imports of Russian gas.

Both Ankara and Moscow prioritize the principle of “mutual benefit” in energy relations – any project or area of collaboration must meet the interests of both countries. One component of their multidimensional affiliations is natural gas. During the Russian and Ukranian gas crisis of 2008 and 2009, as well as when Tehran cut off gas supplies to Turkey in 2007 and 2008 winters, Moscow was extremely agile and cautious in sending additional gas to the Turkish market to remedy the possible negative impacts of shortages. This example and similar practices later on illustrate Moscow’s loyalty to its commitment as a reliable supplier. The mutual benefit or “win-win” principle, often mentioned by Prime Minister Erdoğan, intend to set up a balanced interdependence between the countries, which allows for Moscow and Ankara to collaborate on such great projects as the Blue Stream pipeline and more recently the Akkuyu nuclear power plant project. But, some energy experts in Turkey get anxious and seriously warn the government not to follow a one-sided approach to energy affiliations with Kremlin.

Source: http://enerjienstitusu.com/medya/dogalgaz-anlasmalari-boru-hatlari-m3-rusya-turkiye.jpg

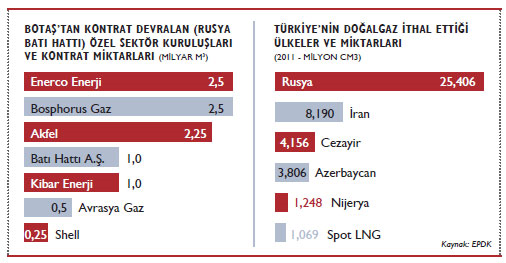

Like many countries, Ankara is laid open to relatively punishing take-or-pay contracts. After a 39% increase in Russian gas prices in 2010, Turkey attempted to renegotiate tariffs, blowing hot and cold over renewing a 6 bcm annual import contract via Western pipeline, running via the Balkans. With the agreement between Gazprom and Botaş not renewed, several private Turkish energy companies were interested in taking over the contract as part of liberalization of the network. Accordingly, Gazprom did sign contracts ranging between 23 and 30 years with private companies, Akfel, Bosphorus, Kibar, and Batı Hattı for the import of 6 bcm a year through the Western pipeline. Certain Turkish energy groups namely Aksa and Bosphorus had already developed projects with Gazprom to import and distribute gas via Turkish network. As seen, the Turkish private sector is increasingly advancing energy affiliations with Moscow and has actually substituted the public sector in the case of these gas contracts. In theory, this should fade Turkey’s negotiating power compared with negotiations between governments, but it must be kept in mind that the Turkish government upholds close connections with the country’s energy groups. Additionally, these private companies are more concentrated on profits and decreasing tariffs – they have guaranteed prices from Gazprom that are up to 40% lower than those paid by BOTAŞ. At the same time, Russian and Turkish authorities envision more gas being delivered, perhaps at lower prices, via the Blue Stream pipeline connecting the two countries through Black Sea. Ankara could therefore play on its status as a main client – representing around 10% of Russia’s gas exports – in a bid to improve its negotiating position.

Source: http://enerjienstitusu.com/medya/turkiye-dogalgaz-ithalati-fiyatlari-fiyati.jpg

Source: http://www.corumgaz.com.tr/Assets/

Blue Stream

This project started with an intergovernmental agreement signed by Russia and Turkey on December 15, 1997. The official inauguration was held on November 17, 2005 and the maximum capacity of this 3.2 billion US dollar pipeline per annum is 16 bcm. This pipeline is one of the significant pipelines bypassing the Ukraine as a transit country.[3] When the project decreases the relative significance of Tbilisi as a transit way within the EU-Russia Geo-energy Field, Kremlin has ensured the gas sale to its second greatest and reliable customer, Turkey, after Brussels for a long time without the existence of transit countries. After the completion of Blue Stream, Turkey has offered the extension of this pipeline to Ceyhan either by prolonging this pipeline or constructing new parallel pipeline named as Blue Stream 2. This is an idea phase and when constructed, Russian gas will subside into Mediterranean and then might reach Lebanon, Israel and even to Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

South Stream

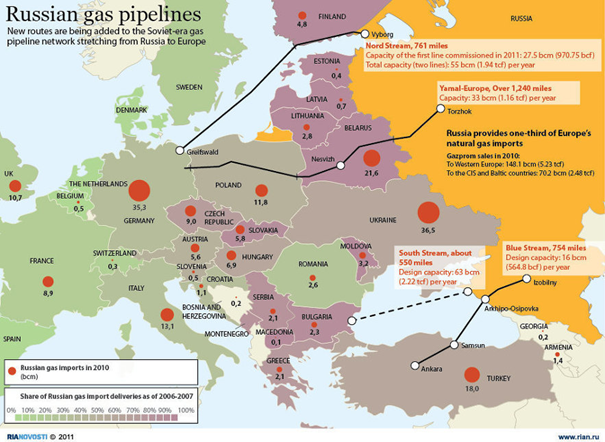

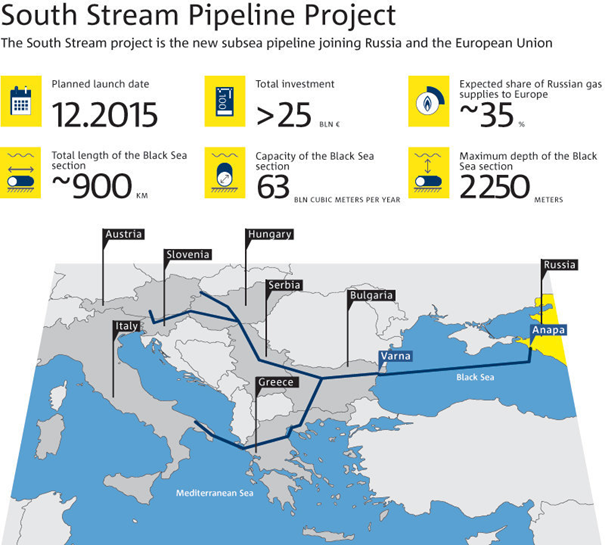

Russian Gazprom and Italian ENI took on a MOU to construct the South Stream Gas Pipeline from Russia to Italy in June 2007. This 3,200 kilometer pipeline, with envisaged capacity of 30 bcm a year, would run across the Black Sea (900 km.) from Russia to Bulgaria, bypassing both Ukraine and Turkey.[4] This pipeline will increase the Brussels’ dependence on Russian energy supplies. It challenges the proposed extension of the EU-backed SCGP via Turkey either to connect to Nabucco pipeline or persist to Greece and Italy. Most fundamentally, South Stream rivals directly with the EU and U.S.-supported Nabucco project. Nabucco’s chances are decreasing as Gazprom is strengthening its influence in Europe and reaching agreements on alternative routes.

Source: http://themoscownews.com/images/19021/00/190210080.jpg

Given the delays experienced in Nabucco Project, Ankara and Moscow signed an agreement on December 29, 2011.[5] The Prime Minister of Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, participated in the signing ceremony of the agreement allowing the construction of the part of South Stream passing from Turkey. After the gas agreements, Igor Seçin, the Vice Prime Minister of Russian Federation, has stated that Turkey would get 25.5 bcm gas in 2012 and this would mean 1.4 times increase compared to 2011. Putin also stated his appreciations to the Turkish government for permitting the construction of South Stream. He expressed his satisfaction for the completion of such a great project that the both countries would have prioritized on energy field as well. He indicated that “We started this dialogue with Prime Minister Erdoğan.”

Source: http://s2.dmcdn.net/PbZZ/526×297-JSI.jpg

Russia’s Gazprom assumed that it has to make investment around 12.5 billion euros ($16.8 billion) to make its domestic gas pipeline system compatible with the scheduled South Stream undersea link to Europe, aggregating the project’s already high cost.[6] The extra expense drives the overall cost to 29 billion euros for the South Stream project under the Black Sea, intended to bypass countries such as Ukraine and Belarus. The bulk of Russia’s gas exports to Europe currently must pass through them. Many analysts indicate that Gazprom is encumbered with inefficiency, high costs and an inflated investment programme. Kremlin’s gas export monopoly had earlier appraised costs for South Stream at 16 billion euros, including 10 billion for its subsea section. Gazprom has additionally allocated 509.586 billion rubles ($16.9 billion) of its long-term investment programme for an advancement of its domestic pipeline system as part of the project.

On March13, 2014, South Stream Board members recently approved the signing of a contract for laying the first string of South Stream’s offshore section and a pipe procurement contract for the second string of the gas pipeline offshore section.[7] On May 16, 2014, Aleksey Miller, Chairman of the Gazprom Management Committee participated in the South Stream Transport Supervisory Board of Directors meeting in Amsterdam. It was underlined in this meeting that that South Stream’s offshore project was ongoing as planned. At present, South Stream Transport has finalized all the contracts necessary for the offshore gas pipeline to pass the construction stage in autumn 2014. Specifically, the company retained orders for the procurement of over 150 thousand pipes for the first two strings of South Stream’s offshore section and did take on contracts for their laying. An agreement was contracted for supplying the process and control equipment for the offshore gas pipeline as well as an agreement for its certification. A contract for transporting gas metering equipment for the Russian and Bulgarian landfall sections is also prepared.The headway with the offshore gas pipeline section represents the proof of fruitful efforts put forward by the European and Russian stakeholders. “Moreover, I am sure that South Stream will also promote cooperation on a larger scale, as the gas pipeline will yield mutual benefit and secure the reliability of energy supply to Bulgaria and Europe as a whole,” said Henning Voscherau, Chairman of the South Stream Transport Supervisory Board of Directors.”

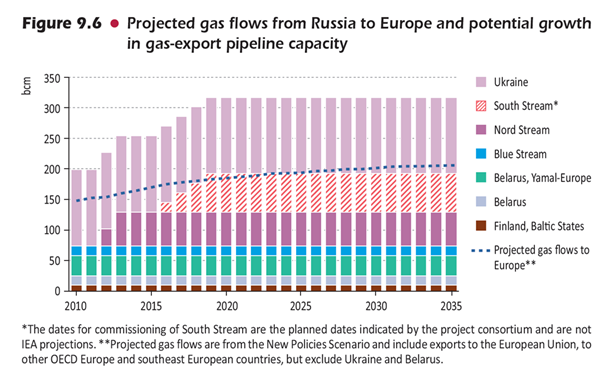

Source: http://m.cdn.blog.hu/gu/gurulohordo/image/iea_fig9_6_russia_gas.png

Samsun-Ceyhan Bypass Oil Pipeline

Bosporus is a 17-mile long waterway connecting the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles is a 40-mile long waterway linking the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. Both take place in Turkey and supply Western and Southern Europe with oil from the Caspian Sea Region.[8] Estimated 2.9 million bbl/d oil flowed through the Turkish Straits in 2010. The ports of the Black Sea are one of the chief oil export routes for Russia and other former Soviet Union republics. Oil shipments through the Turkish Straits lessened from over 3.4 million bbl/d at its peak in 2004 to 2.6 million bbl/d in 2006 as Russia shifted crude oil exports toward the Baltic ports. Traffic through the Straits augmented again as crude production and exports from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan increased in recent years. Only half a mile wide at its narrowest point, the Turkish Straits are regarded as one of the world’s most difficult waterways to navigate due to its agile geography. With 50,000 vessels, including 5,500 oil tankers, passing through the straits annually, it is also considered as one of the world’s busiest chokepoints. Given the heavy tanker traffic, as well as the physical characteristics and peculiarities of the Turkish Straits, a maritime disaster caused by a tanker transporting hazardous cargo seems likely sooner or later. In addition to the humanitarian and environmental perils, such an accident would cut off the regular oil flow to world markets. Therefore, the solution is the use of alternative oil export options bypassing the Straits. Among the various by-pass offers, Ankara has supported the Samsun-Ceyhan By-Pass Oil Pipeline.[9] The advantages of this project can be put forward as follows:

|

|

|

The pipeline, envisaged to be built, starts from Ünye, located on the north of Samsun, reaches to Sivas and then goes parallel with BTC. Given this feature, this pipeline will be able to benefit from the passing right. For the last few years, this pipeline project has been on the agenda of Ankara-Moscow relations. But it should not be forgotten that Kremlin also has Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline project that will pass from Bulgaria and Greece and also bypass Bosphorus. In reality, the attainment of this project is vague given Sofia’s rejection for ecological concerns. It is wondered that which of these projected pipelines will be constructed. Samsun-Ceyhan Oil Pipeline Project was suspended by Russia due to this pipeline’s being uneconomical in September 2011.

Nuclear Energy Projects of Turkey and the Russian Federation

The fact is that Ankara, though endeavoring to lessen its economic dependency, has a tendency toward expanding the scope of its partnership with Kremlin, which is increasingly participating in Turkish energy projects.[10] This is underscored mainly by the inclusion of nuclear power to the energy relationship between the two countries. Ankara has been regularly expressing its intention to advance a nuclear power program for more than 40 years. In May 2010, it finally reached its intention by signing an agreement with Rosatom worth more than $20 billion for the construction by 2019 of a nuclear power station having four reactors and a capacity of 4,800 megawatts at Akkuyu on the Turkish Mediterranean Sea coast. In Turkey, this agreement has been harshly criticized given the cost of the project and increasing the dependence on Moscow. The contract includes some aspects that are politically and economically startling. Rosatom, which is sponsoring the construction, will at the first phase possess 100% of the plant and will subsequently sell only a minority stake (49%) to another investor, leaving the door open for the Turkish government to participate the project. The Turkish authorities have also decided that state-owned electricity distribution company TEDAŞ will get a fixed price over 15 years 70% of the power generated by the first two reactors and 30% of the power generated by the third and fourth reactors. Technical concerns have also been upraised after the Fukushima disaster, due to the seismic activity in this part of Turkey.

| Potential Conflict Areas between Turkey and Russian Federation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

For the last 20 years Ankara and Moscow have been advancing from rivalry to something that might be defined as a real strategic partnership. One can talk about the collaboration fields between Turkey and Russian Federation in the region encompassing from Middle East to Cyprus. In innumerable cases, Moscow and Ankara do hold touching policies; in others, both would do well from tapering their dissimilarities. More policy cooperation between the two regional players would be beneficial for the two countries as well as for the whole Eurasia region.

For me, Ankara’s collaboration with Moscow and Tehran is intended for only the branching out Turkish energy supplies. Given Turkey’s so much dependence on energy supplies from abroad for meeting its increasing demand, it is not possible for Turkey to terminate imports from Moscow and Tehran in the short term as well as in the medium term.

Consequently, given the so close economic relations between Turkey and Russian Federation, the Southern Gas Corridor will not be seriously affected. Turkey advocates the idea that the natural gas pipeline projects and the pipeline projects comprising the Southern Gas Corridor are not rival to each other. Turkey is of the opinion that these projects are complementary with each other and both will be vital for the energy security of Europe in the near future. Time will better show this.

Sina KISACIK

[1] Tuncay Babalı, “The Role of Energy in Turkey’s Relations with Russia and Iran”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Paper Prepared for International Workshop, “The Turkey, Russia, Iran Nexus: Economic and Energy Dimensions”, 29 May 2012, http://csis.org/files/attachments/120529_Babali_Turkey_Energy.pdf, p. 4, (Date of Accession: 22 January 2014).

[2] Remi Bourgeot, “Russia-Turkey: A Relationship Shaped by Energy”, Russia/ NIS Center, in cooperation with the Turkey Program, IFRI, Russie. Nei. Visions No. 69, March 2013, pp. 9-10.

[3] Volkan Ş. Ediger and Itır Bağdadi, “Turkey-Russia Energy Relations: Same Old Story, New Actors”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 12, No. 3 (2010): pp. 231-232.

[4] Greg Bruno, “Turkey at an Energy Crossroads”, Council on Foreign Relations, 20 November 2008, http://www.cfr.org/turkey/turkey-energy-crossroads/p17821, (Accessed 9 February 2013).

[5] Neşe Karanfil, “Doğalgazda yeni yıl hediyeleri!”, Radikal, 29 December, 2011, http://www.radikal.com.tr/Radikal.aspx?aType=RadikalDetayV3&VersionID=96727&Date=30.12.2011&ArticleID=1073886, (Accessed 30 December 2011).

[6] Vladimir Soldatkin, “Gazprom puts total South Stream costs at 29 bln euros”, Reuters, January 29, 2013, Accessed January 30, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/29/gazprom-southstream-investment-idUSL5N0AY72I20130129.

[7] South Stream Official Web Site, “All contracts for South Stream’s offshore construction signed”, 16 May 2014, http://www.south-stream.info/en/press/news/news-item/all-contracts-for-south-streams-offshore-construction-signed/, (Accessed 30 May 2014).

[8] US Energy Information Administration, “World Oil Transit Chokepoints,”22 August 2012, http://www.eia.gov/countries/regions-topics.cfm?fips=WOTC&trk=p3, (Accessed 19 January 2013).

[9] http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkeys-energy-strategy.en.mfa.

[10] Bourgeot, “Russia-Turkey: A Relationship Shaped by Energy”, pp. 10-11.