Introduction

Mass flows of refugees forced the international community to act at the global, regional, national, and local levels. Among the regional responses, the EU-Turkey deal was one of the most significant ones with respect to the governance of mass refugee flows from Syria. The deal opened a new chapter in relations between the EU and Turkish government and became one of the most controversial issues of this time. Despite the fact that the agreement has been running for three years, there are still several hitches, with particularly the question of funding still not completely settled.

EU-Turkey relations and its importance

Turkey is important partner for the EU. Turkey’s relationship with this organisation are rooted in several factors. Turkey applied for EU membership in 1987 and accession talks began in 2005. Currently, relations are affected by the domestic politics both in the country and the EU, while conflicts at Turkey’s borders in Syria have implications for the security and for migration flows toward the EU. Turkey is definitely situated at a very strategic location for European security and economy. The EU-Turkey economic relationship plays important roles both ways, especially in case of trade, foreign direct investment, and technology transfers[1]. Turkey is the EU’s 5th largest trading partner. The cooperation between the EU and Turkey on refugees has disrupted the human trafficking networks; therefore, the political solution in Syria is the ultimate and the main objective of relationship.[2]

The EU refugee crisis and its background

The Syrian civil war, which began nine years ago, has been a continuous tragedy for Syrians. Half a million lost their lives, and around 12 million have been displaced. Of those displaced, more than 6 million fled internally, while over 5.6 million went to neighbouring countries, which make Syrians the largest refugee population in the world. Neighbouring Turkey has welcomed more than 4 million refugees from Syria and elsewhere; thus, becoming the country hosting the largest refugee population in the world.

The EU refugee crisis of 2015 clearly established that this population is also a matter of concern for the European Union (EU), when over 850,000 refugees, mostly Syrians, crossed the Aegean Sea between Turkey and Greece to seek asylum on EU soil. The crisis is still remembered for disruptive and upsetting events such as the deaths over 800 people en route and an international breakdown of solidarity disturbing the lives of hundreds of thousands of refugees.[3] Amid the panic and chaos caused by the sudden migratory influx, the “Common European Asylum System” strained and was unable to manage the crisis. Instead, member countries pursued their own distinctive policies. While some did not even admit a single refugee, a country like Germany welcomed one million refugees in as short a period as one year.

The uncontrolled arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants triggered grave political consequences for the EU, resulting in the rise of extreme right and xenophobic rhetoric, damaging harmonious cooperation between the member states and threatening fundamental values as openness, tolerance and respect for human dignity.[4] Against this background, the EU political elite chose to contain the crisis not by international solidarity, but by practical measures aimed at slashing the migratory influx from Turkey. Turkey has invested significantly to respond to the needs of 3.6 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey, providing them with humanitarian and social assistance, education, health and other services. It is the largest refugee community in the world. After more than a million Syrian refugees reached Europe primarily via the Turkey–Greece sea route and dispersed throughout the continent in 2015, Turkey and the European Union (EU) began a close cooperation to stem the influx of refugees under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey and signed the EU–Turkey statement on March 18, 2016.[5] By May 2019, out of EUR 6 billion mobilised by the EU, more than 80 projects had been launched and more than EUR 2.2 billion has been disbursed.[6]

What are the provisions of the agreement?

The main purpose of the EU-Turkey statement was to prevent the loss of lives and to dismantle human trafficking networks, but the more important reason for the deal was to prevent refugees from reaching Europe. Under the agreement, Syrian refugees are exchanged between Turkey and EU countries. The arrangement is that the EU sends all Syrians who reached the Greek islands illegally after March 20, 2016, back to Turkey. In return, legal Syrian refugees are accepted into the EU.[7]

It was agreed that in exchange for Turkey’s cooperation with the EU on curbing illegal migration to Europe (by returning migrants reaching Greece irregularly and taking back irregular migrants intercepted in Turkish waters), the EU would support Turkey with two tranches of 3 billion euros (dispersed through the Facility for Refugees) with projects aiming to address the urgent needs of refugees and host communities in Turkey.[8] By the end of 2017, the EU had fully committed and contracted €3 billion under the first tranche with 72 projects rolled out, showing tangible results, with more than €2 billion disbursed. The EU is currently mobilising the second tranche of Facility funding and has already committed €1.2 billion, of which €450 million has been contracted and €150 million disbursed. Facility funding goes to projects to address the needs of refugees and host communities with a focus on humanitarian assistance, education, health, municipal infrastructure and socio-economic support.[9]

According to the United Nations, Turkey has been hosting 2,900,000 refugees. Turkey, however, says that their number recently rose to around 3,500,000. According to the EU Commission, €3 billion has already flowed into Turkey to cover the costs of educating half a million Syrian children.[10] Because return procedures in Greece are slow, only 1,564 Syrians were sent back to Turkey between 2016 – 2018. In addition, a further 600 Syrians were sent back to Turkey under the agreement between Turkey and Greece. In exchange, 12,489 Syrians from Turkey were resettled in EU countries. Germany took in 4,313, the Netherlands 2,608, France 1,401 and Finland 1,002 Syrian refugees. The EU member states Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic (Czechia), Bulgaria and Denmark did not accept any refugees at all[11].

File photo, children play at a makeshift refugee camp outside Moria on the northeastern Aegean island of Lesbos, Greece (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris, File) https://www.apnews.com/2eb94ba9aee14272bd99909be2325e2b

The other aspects of the March 18 statement are: the acceleration of Turkey’s accession negotiations; the acceleration of modernization negotiations on the Customs Union; cooperation in terms of counter-terrorism; dialogue meetings on energy, transport and economy; and acceleration of the visa liberalization process. Assessing progress in these areas, we should underline that while two chapters have been opened and it has been decided to work on the 5 chapters which are politically blocked, the accession negotiations are at a standstill point. The EU Parliament recommended also to suspend of accession negotiations with Turkey. Negotiations on the Customs Union are also politically blocked.[12]

Results of the common statement

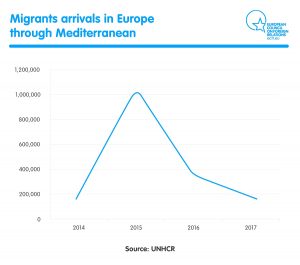

The impact of the EU-Turkey Statement had immediate and tangible results. Thanks notably to the cooperation with the Turkish authorities, arrivals decreased significantly – showing clearly that the business model of smugglers exploiting migrants and refugees can be broken. From 10,000 in a single day in October 2015, daily crossings have gone down to an average of 83 today, while the number of deaths in the Aegean decreased from 1,175 in the 20 months before the Statement to 310. That is almost one million people who have not taken dangerous routes to get to the European Union, and more than 1,000 who have not lost their lives trying.[13]

Through the EU-Turkey Statement, irregular and dangerous crossings have been substantially reduced, which has contributed to saving lives. Thanks to the work with the Turkish authorities, the EU also reduced the chaotic and irregular migration along new routes, in particular as regards to the Eastern Mediterranean route. Irregular migratory flows decreased from 10,000 arrivals per day from Turkey to the Aegean islands in the peak period of 2015, to a daily average of 88 in 2018.[14]

From 2016, as a result of the agreement, the number of refugees entering Europe illegally via the Aegean Sea decreased. Even though numbers were far below those of 2015 when the crisis began, Gerald Knaus, the mastermind behind the refugee pact and chairman of the European Stability Initiative (ESI), believes the agreement is in danger. According to Knaus, in the first half of 2017, almost 9,000 people came to Europe via the Aegean Sea, while in the second half of the year this figure had risen to 20,000. But according to the EU Commission, the number of refugees who came to Greece via Turkey fell by 97 percent compared to the period before the agreement.[15]

Migrants arrivals in Europe through Mediterranean, 2014-2017

According to the European Commission, Turkey is moderately prepared in justice, freedom and security. There has been some progress in the past year, in particular in migration and asylum policy. Turkey continued to make significant efforts in hosting and addressing the needs of almost four million refugees, and in preventing illegal crossings towards the EU. Turkey remained committed to implementing the March 2016 EU-Turkey Statement and played a key role in ensuring effective management of migratory flows along the Eastern Mediterranean route. There has been limited progress in the implementation of the recommendations of last year’s report, but Turkey is not yet implementing the provisions relating to third-country nationals in the EU- Turkey readmission agreement, despite these entering into force in October 2017.[16]

Additionally, the EU-Turkey Statement has transformed the nature of relations, turning it into a transactional model in which the EU and Turkey cooperate on shared common interests (i.e. counter-terrorism, energy, trade and migration) putting aside value-based questions. However, the success of the statement should not only be measured in terms of numbers but also in terms of its legality and implementation. Its legality continues to be challenged and its implementation has resulted in alleged human rights violations as documented by international NGOs. However, on 2019 were held many discussions at the EU institutions in Brussels and some Member States on the effectiveness of the implementation of the EU-Turkey statement and the way forward in EU-Turkey relations.

Main problems in mutual relations

Firstly, Turkey repeatedly threatened to terminate the agreement because, the EU has not paid the stipulated amount. For the EU, the question has been how to get the money together, while for Turkey the more important issue has been when the money would arrive. The main hurdle has been the differing views held by Turkey and the EU on how the funds should be used. While Turkey has been applying pressure and, above all, has wanted to satisfy the overriding needs of the refugees, there have been delays because the EU member states’ funds have had to be monitored by the EU. Moreover, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan threatened the EU with reopening the migratory routes to Europe if Turkey does not receive more economic support, outgoing EU migration commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos told Euronews that ‘the EU-Turkey statement should remain alive (…) [and] not be used as a negotiating tool’[17].

Secondly, the visa freedom for Turkish citizens provided for under the agreement has not been implemented. The lifting of visa requirements for Turkish citizens going to EU countries depends on Turkey delivering on its part of the agreement that it will readmit all migrants who illegally cross to Europe from Turkey, as well as the implementation of the 2013 ‘Visa Roadmap’. It needs to remind that Turkey has already met 66 benchmarks out of 72 and believed that Turkey can accelerate its work on the remaining 6 benchmarks.[18] Turkey’s pro-government Anadolu Agency (AA) reported that president Recep Tayyip Erdogan is stepping up internal pressure to meet the criteria for the process of visa-liberalization dialogue with the European Union.[19]

Thirdly, there is the problem with status of Syrian refugees in Turkey, who do not have official refugee status. For this reason, their conditions do not meet international standards of protection. Around 1,000 Syrians are placed under temporary protection per day and more than 3.5 million Syrians are under protection. This status gives them the right to education and health care.

Fourthly, Turkey still needs to align its legislation on data protection to allow for police and judicial cooperation with Europol and Eurojust, as well as on border management and on the fight against terrorism.

Fifthly, the view in European capitals is that Turkey has distanced itself from the EU’s democratic norms to such a degree that progress on Turkey’s EU accession bid is no longer realistic. The June 2018 EU Council conclusions stated clearly the concern in Europe over ‘the continuing and deeply worrying backsliding on the rule of law and on fundamental rights including the freedom of expression’ and ‘the deterioration of the independence and functioning of the judiciary’. The accession process is neither alive nor formally dead, because it is up to Turkey to fulfill the conditions that the two sides have agreed are the basic requirements for accession.[20] The risk is that in the absence of a positive dynamic on accession, the relationship will become purely transactional.[21]

Given the absence of credible signals from Ankara on a return to the rule of law in 2019, it is clear that a degree of transactionalism will inevitably be part of the future Turkey-EU relationship. But the challenge will be whether Ankara and Brussels can still nurture some rules-based order. Four areas of potential cooperation stand out: the customs union, counter-terrorism, visa liberalization, and economic and political dialogue. According to the European Commission president-elect Ursula von der Leyen, Turkey has not made any progress towards possible future membership of the European Union. ‘As regards Turkey, I have not seen this progress in the last years. On the contrary, Turkey needs to show that it wants to be closer to European values, to European rules, the rule of law, liberty and fundamental values’.[22]

Recommendations for the future

For the coming year, Turkey should in particular:

- Continue implementing the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016 and implement all the provisions of the EU-Turkey readmission agreement towards all EU Member States;

- Align legislation on personal data protection with European standards, and implement the necessary requirements for the negotiation of an international agreement allowing for the exchange of personal data with Europol and Eurojust;

- Revise its legislation and practices on terrorism in line with the European Convention on Human Rights, European Court of Human Rights case law and the EU acquis and practices. The proportionality principle must be observed in practice[23];

- Turkish and European politicians should not use this humanitarian crisis as a political tool. The rise of xenophobia and nationalism is a threat both for Turkey and the EU and there needs to be stronger political narrative that highlights inclusion rather than exclusion in dealing with the refugee crisis;[24]

- The most realistic option for the rules-based component of the relationship is the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union – the trade deal, which was concluded more than two decades ago. Its modernization must involve not only the expansion of its scope to services and possibly agriculture, but also horizontal areas such as the monitoring of state aid and, more importantly, a more functional dispute-settlement mechanism. The latter is important to resolve the ever-larger number of disagreements over the functioning of the regime.[25]

Conclusion

To summarize it, relationship between the EU and Turkey are very tense. In the coming months, domestic politics on both sides and the international environment will probably not help much. The European Union is facing an institutional crisis. There is rising xenophobia and Islamophobia in Europe, threatening the core values of the EU, such as human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, and respect, for human rights. This threat is not limited to the EU but it also affects Turkey, a country that much needs the EU’s guidance and support on good governance. As the EU loses its role and credibility as an anchor for democracy and human rights for Turkey, we see a rising euro-skepticism and anti-Westernism in Turkey. In order to avoid this intolerance, there needs to be continuous dialogue, joint work and mutual trust between the two parties.[26] However, if Turkey will refuse to improve its rule-of-law situation, this would be a major reason for EU to prolong the standstill. Ankara’s artificial narrative to the effect that Turkey has fulfilled all the criteria for accession does not help politically. In addition, political trends in several EU countries are not favourable to Turkey, as the campaign for the May 2019 European Parliament elections was illustrating.[27] The latest European Commission progress report has warned that Turkey is moving away from Europe.

Little progress on the country’s accession is expected under the new EU legislature in 2019-2024, but we can’t expect major negative changes either, as long as the refugee deal is in place. Now the question is how the new Parliament and Commission will handle the sensitive relations with Turkey. Certainly, a sustained deterioration of the political, economic, and security relationship will run counter to both Turkey’s and the EU’s interests. All stakeholders should therefore pursue with determination the search for realistic prospects for positive developments. The possibility of a complete standstill in the EU-Turkey relationship should not be underestimated.

Cover Photo: euobserver.com

Dr. Beata PISKORSKA

[1] Marc Pierini, “Options for the EU-Turkey Relationship”, Carnegie Europe, May 03, 2019, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2019/05/03/options-for-eu-turkey-relationship-pub-79061.

[2] “EU-Turkey relations and the migration conundrum: where does the EU-Turkey Statement stand after three years?”, Atlantic Council, May 15, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/event-recap/eu-turkey-relations-and-the-migration-conundrum-where-does-the-eu-turkey-statement-stand-after-three-years/.

[3] “The EU-Turkey Statement on migration: Three years on”, https://www.globalutmaning.se/utblick/eu-turkey-statement-migration-three-years/.

[4] “The EU-Turkey Statement on migration: Three years on”, https://www.globalutmaning.se/utblick/eu-turkey-statement-migration-three-years/.

[5] “EU-Turkey relations and the migration conundrum: where does the EU-Turkey Statement stand after three years?”, Atlantic Council, May 15, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/event-recap/eu-turkey-relations-and-the-migration-conundrum-where-does-the-eu-turkey-statement-stand-after-three-years/.

[6] “Turkey 2019 Report”, Accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2019 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, {COM (2019) 260 final} Brussels, 29.5.2019 SWD (2019) 220 final.

[7] European Council 2016, “EU-TurkeyStatement”, March 18, 2016. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press -releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement/, Accessed on 22.09.2019.

[8] €3 billion from the EU budget and €3 billion contributed by EU Member States – in two tranches.

[9] “EU-TURKEY STATEMENT Three years on”, March 2019 , European Commission.

[10] “The EU-Turkey refugee agreement: A review”, DW, https://www.dw.com/en/the-eu-turkey-refugee-agreement-a-review/a-43028295.

[11] “The EU-Turkey refugee agreement: A review”, DW, https://www.dw.com/en/the-eu-turkey-refugee-agreement-a-review/a-43028295.

[12] European Council 2016, “EU-Turkey Statement”, March, 18, 2016, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press -releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement/, Accessed on 22.09.2019.

[13] “EU-TURKEY STATEMENT Three years on”, European Commission, March 2019.

[14] Turkey 2019 Report, Accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 2019 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, {COM (2019) 260 final} Brussels, 29.5.2019 SWD (2019) 220 final.

[15] “The EU migrant relocation and resettlement scheme – what you need to know”, DW, https://www.dw.com/en/the-eu-migrant-relocation-and-resettlement-scheme-what-you-need-to-know/a-40378909.

[16] The EU migrant relocation and resettlement scheme.

[17] “Avramopoulos: EU-Turkey deal must ‘remain alive'”, EU Observer, 12 September 2019, https://euobserver.com/tickers/145924.

[18] “Turkey ups pressure on visa-free entry into EU”, EU Observer, 19.09.2019, https://euobserver.com/tickers/145985.

[19] Turkey ups pressure on visa-free entry into EU.

[20] Marc Pierini, “Options for the EU-Turkey Relationship”, Carnegie Europe, May 03, 2019, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2019/05/03/options-for-eu-turkey-relationship-pub-79061.

[21] That is already the case in many collaborative policy areas, such as the 2016 ‘refugee package’ – the EU provides Syrian refugees and their host communities in Turkey with €6 billion ($6.8 billion) of aid, or foreign policy dialogue.

[22] “Von der Leyen: no progress in Turkey’s EU bid”, EU Observer, September 11, 2019, https://euobserver.com/tickers/145909.

[23] “Managing the Refugee Crisis: Commission reports on progress made in the implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement”, Brussels, June 15, 2016, https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2181_en.htm.

[24] Pınar Dinç & Irem Aydemir, “The EU-Turkey Deal: Ambiguities and Future Scenarios Eurocrisis in the Press”, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/eurocrisispress/2016/10/27/the-eu-turkey-deal-ambiguities-and-future-scenarios/.

[25] Marc Pierini, “Options for the EU-Turkey Relationship”, Carnegie Europe, May 03, 2019, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2019/05/03/options-for-eu-turkey-relationship-pub-79061.

[26] Pınar Dinç & Irem Aydemir, “The EU-Turkey Deal: Ambiguities and Future Scenarios Eurocrisis in the Press”, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/eurocrisispress/2016/10/27/the-eu-turkey-deal-ambiguities-and-future-scenarios/.

[27] Zeynep Atilgan, “No new phase seen in EU-Turkey relations after EP elections”, Euractive.com, 31.05.2019, https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/no-new-phase-seen-in-eu-turkey-relations-after-ep-elections/.