“Jazz is about freedom within discipline. Usually a dictatorship like in Russia and Germany will prevent jazz from being played because it just seemed to represent freedom, democracy and the United States.” – Dave Brubeck[1]

Jazz: A Music Genre with a Political Background

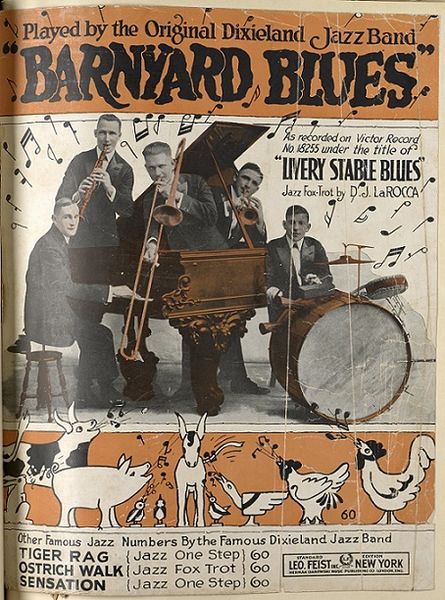

Jazz was born as a music genre in the early 20th century in the United States.[2] Jazz is music is often associated with African Americans who were then not accepted as first-class citizens in the U.S. as well as in many European countries. Jazz, in a sense represented the repressed political and socioeconomic status and pains of African Americans[3], who had to resist and fight back still many decades to come in order to reach equal status with white people though the slavery was already abolished in 1865. Thus, jazz music is already a political music wave from its birth; it was the music of the oppressed, but strangely enough, it became the favorite music genre of the riches of Western societies, as well as intellectuals, in other words the music of the elite, starting from the 1940s. Jazz reflected the pains and stories of African Americans and in time, it became an important cultural aspect of the United States. Jazz became popular in the U.S. first time in 1917, with the recordings of Dixieland Jazz Band.

Dixieland Jazz Band Barnyard Blues – 1917 Leo Feist, New York

Etymology

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines jazz as “a type of American music with lively rhythms and melodies that are often made up by musicians as they play”.[4] According to Wikipedia, the question of the origin of the word jazz has resulted in considerable research, and its history is well documented. It is believed to be related to jasm, a slang term dating back to 1860 meaning “pep, energy”.[5] The earliest written record of the word is in a 1912 article in the Los Angeles Times, in which a minor league baseball pitcher described a pitch, which he called a jazz ball “because it wobbles and you simply can’t do anything with it”.[6] The first use of the word in relation to music on the other hand is seen in 1915 in a Chicago Daily Tribune article.[7] Its first documented use in a musical context in New Orleans was in a November 14, 1916 Times-Picayune article about “jas bands”.[8] In time, jazz was approved as a universal word (term) for making reference to this new type of music that was born in America. In nearly all popular languages, the term “jazz” is used for the same meaning; in Turkish also the word “caz” represents the jazz music.

Jazz: History and Characteristics

Jazz is historically divided into two main categories; gospel jazz and blues.[9] The first one, gospel jazz, is derived out of African American churches in the U.S. where many talented artists and singers were raised as part of church choirs by singing gospel songs before singing jazz. Gospel jazz, thus, carries strong influence from gospel music and Christianity (Protestantism especially). The second one, blues, on the other hand, is born in New Orleans and influenced from African American artists’ new music style. Especially, “ragtime” style, first implemented by Scott Joplin, had an important effect over the development of blues. Later, with the effect of European harmonies, jazz was born in the 1930s during the “swing” era with unforgettable names including Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong and Fats Miller Swind.[10]

In addition, jazz is often defined as “free music” since it is based on improvisation skills and contains larger freedoms for different harmonic styles.[11] According to jazz critic Nat Hentoff, the most important characteristics of jazz music are “pulsating rhythms, sense of improvisation, a special technique of vocalized instrument and polyrhythm”.[12] Kahyaoğlu on the other hand thinks that, jazz is open to experiments ad improvisation thanks to its nature.[13] The centrality of improvisation in jazz, in fact, comes from blues.[14] Keseroğlu divides jazz history into 10 categories[15];

- 1890-1900: Ragtime style

- 1900-1910: New Orleans style

- 1910-1920: Dixieland style

- 1920-1930: Chicago style

- 1930-1940: Swing style

- 1940-1950: Bebop style

- 1950-1960: Cool jazz and Hard Bop style

- 1960-1970: Free Jazz style

- 1970-1980: Electric Jazz style

- 1980-1990: New styles.

Jazz music is made mostly by instruments including trumpet, trombone, clarinet, saxophone, piano, keyboard, synthesizer, guitar, bass guitar, drum, percussion and violin. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Bannet, Benny Carter, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Bill Evans, Dave Brubeck, Chick Korea, Bessie Smith, Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra, John McLaughlin and Norah Jones most popular jazz artists in the world. In Turkey, there are important jazz musicians as well such as Okay Temiz, İlhan Erşahin, Birsen Tezer, Nükhet Ruacan, Kerem Görsev, Tuna Ötenel and Jülide Özçelik.

The first widespread popularity of jazz took place in the 1920s, especially after the Prohibition. Due to Volstead Law and Prohibition, alcoholic drinks were forbidden in the U.S. then and people had to meet in illegal speakeasies to drink alcohol. Speakeasies were also the centers of jazz music since many young and talented African American artists were performing in these clubs. At those years, jazz had a very negative reputation for being an immoral and degenerate; threatening the already existing values of the American society. For instance, Professor Henry van Dyke of Princeton University wrote: “…It is not music at all. It’s merely an irritation of the nerves of hearing, a sensual teasing of the strings of physical passion.” for jazz.[16] Since these clubs and alcohol were associated with mafia and crime during these years, jazz was not very respected among the white American conservative elite.

Glenn Miller: A concrete example showing that jazz was (is) not only for African Americans

In the 1930s, thanks to swing big bands, jazz became a more popular music genre and began to have fans from white Americans as well. Key figures in developing the “big” jazz band included bandleaders and arrangers Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Harry James and Jimmie Lunceford. Swing was also a dance music; so, jazz entered from speakeasies to dance clubs, hotels and concert halls first time in the 1930s. In the 1930s, jazz spread to Europe as well. In France and United Kingdom, European jazz artists emerged and contributed a lot to the development of American jazz. Many of the jazz standards were composed in the 1930s.[17]

In the 1940s, thanks to amazing artists such as Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie and the emergence of bebop style, jazz music opened a new page and continued to develop. Ellington called his music as “American music” rather than jazz. Most of today’s jazz standards in fact were produced in the 1940s. Thus, 1940s were the rising years of the jazz music. It coincided with the end of Second World War and the emerging optimistic and positive mood of European and American people after terrible devastating years of the World War.

Throughout the 1950s, jazz continued to became more popular and spread to the whole world especially in the Western bloc. Many important composers and singers came out and became popular in the 1950s. Golden years of the jazz coincided with the rise of American power throughout the world with the emergence of NATO and the start of American economic and cultural programs. Many of the jazz classics were created in the 1950s. The spread of democracy strengthened the spread of jazz since they were both based on the idea and notion of freedom (improvisation in music and liberties in politics). Thus, 1950s were the golden years of the jazz music and maybe the only decade when it became the most popular music genre in USA. During the 1950s, the jazz also entered into many countries (e.g. Turkey) that became U.S. ally during the Cold War conditions due to rising Soviet expansionism danger.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the jazz music was enriched due to new styles emerging in the rest of the world such as Afro-Cuban jazz, Latin jazz, Brazilian jazz etc. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was also developed thanks to the pioneering efforts of some musicians such as Miles Davis. Jazz began to be overshadowed by emerging music types such as rock & roll, but continued to develop. In 1987, the United States House of Representatives and Senate passed a bill proposed by Democratic Representative John Conyers Jr. to define jazz as a unique form of American music, stating: “…that jazz is hereby designated as a rare and valuable national American treasure to which we should devote our attention, support and resources to make certain it is preserved, understood and promulgated.”[18]

In the 1980s, the jazz began to be forgotten by the emergence of disco and pop music but efforts for the resurgence of traditionalism also began in the U.S. Starting from the 1980s, jazz became the favorite music of enlightened minorities in many societies. It continued to develop due to music festivals and jazz organizations but never became a popular music genre as in the 1940s and 50s.

Jazz and Women

Jazz is a political music by its nature and represents the response of the gifted oppressed groups, but its relation to women is also highly political. Women jazz performers and composers such as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Ethel Waters, Betty Carter, Adelaide Hall, Abbey Lincoln, Sarah Vaughan and Anita O’Day have contributed a lot to the development and popularity of this music genre throughout the jazz history. While women such as are famous for their jazz singing, women have achieved much less recognition for their contributions as composers, bandleaders, and instrumental performers. In none of the other music genres women played such an important role as in the jazz.

Billie Holiday

Margaret Howze also pointed out the unique and pioneering role of women in jazz music. Other than well-known performers (singers), according to Howze, there are many unknown female jazz heroes (instrumentalists and composers) in jazz history. Moreover, jazz was a liberating music in terms of women rights. Musicologist Ingrid Monson pointed out that the piano, one of the earliest instruments that women played in jazz, allowed female artists a degree of social acceptance.[19] Trumpeter Dolly Jones, later known as Dolly Hutchinson, was one of the earliest jazz women to record. Valaida Snow, once known as “the Queen of the Trumpet” was another female pioneer of the trumpet and her playing was often compared to that of the great Louis Armstrong. In the 1920s and ’30s, there were a growing number of women jazz pianists – Sweet Emma Barrett, Billie Pierce, Jeanette Kimball and Lovie Austin among them. The most famous to emerge from that era was the legendary Mary Lou Williams.[20]

Ella Fitzgerald

Howze thinks that, nearly a century after the birth of jazz and the rise of the women’s rights movement, female jazz artists are still likely to get skeptical looks if they’re playing instruments like the saxophone, the trumpet, or the drums.[21] However, she adds that “an increasing number of formal jazz schools like Berklee College of Music and the New School in Manhattan, opportunities for female jazz artists are also on the rise.”[22] The schools show increased enrollments from women in jazz studies, proving once again that jazz is no longer “the boy’s club”. Considering the help of jazz in the improvement of the socioeconomic status of African American women, one can also claim that jazz is the music of women similar to many other oppressed groups.

Theodor Adorno and Criticism of Jazz

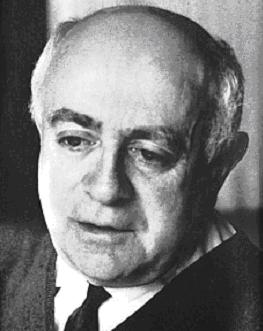

Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund Adorno (1903-1969) was a German sociologist, philosopher, musicologist and composer. He was a member of the Frankfurt School along with Max Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Jürgen Habermas and many others. Theodor Adorno was no doubt one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. Affected by Walter Benjamin’s application of Karl Marx’s thought, he argued that capitalism fed people with the products of a culture industry (the opposite of true art) to keep them passively satisfied and politically apathetic. Adorno thought that the capitalist system had not become close to collapse, as the famous German philosopher Karl Marx had predicted. Instead, he saw that capitalism had seemingly become more powerful and widespread. He was pretty negative about our chances of breaking out of this system. Adorno mostly dealt with the cultural aspects (superstructure) of capitalism. Adorno thought that in modern capitalist societies there is an economy of cultural goods which has a specific logic. He believed that cultural needs are the product of education and social origin. Thus, social hierarchy among consumers reflects itself on the socially recognized hierarchy of arts. Thus, arts in a sense function as “markers of class”. Education and social class determines a person’s tastes and develops his/her competence for different kind of arts. That is why, a work of art has meaning and interest only for someone who possesses the cultural competence, that is, the code, into which is encoded. Adorno identified popular culture as the reason for people’s passive satisfaction and lack of interest in overthrowing the capitalist system. He claimed that the capitalist system brings problems such as taking away individual “true” needs like freedom, full expression of human potential and creativity, genuine creative happiness and replacing them with false ones like commodity fetishism, popular culture and standardization. Adorno also discussed “use value” and “exchange value”. Use value refers to the contingent qualities of a thing that are useful to human beings. Exchange value on the other hand refers to the popularity, scarcity and the price of a thing. For example, water’s use value is very high because it is a vital drink but its exchange value is very low because it is not scarce. In contrast, a diamond is very low in use value but its exchange value is enormous because it is very scarce.[23]

Theodor Adorno

Following this logic, Adorno asserts that the popular music genre that emerged simultaneously with the rise of bourgeoisie, the classical music represents the true art. Classical music is planned and based on the great artistic talents of immortal European composers like Mozart, Beethoven, Vivaldi, Chopin etc. Since there was not a developed music industry in the 18th and 19th century Europe, in classical music use value (in this case the quality of the music) mattered first. Classical music was developed and existed in bourgeois houses and concert halls. This meant high-quality music for Adorno.[24] Adorno believed, contrary to classical music, jazz music and other genres of American popular music represent the industrialized form of art, where the exchange value dominates over the use value. This meant the imposition of certain tastes over people by the industry in accordance with the preferences of the sovereign classes. That is why; jazz was an industrial music for Adorno and represented the low-quality. Adorno did not like the jazz music and never considered it as the true symbol of African Americans to slavery. Instead, for him, jazz was the half-sad complaint of African Americans against white domination.[25] Adorno’s writings on jazz remain at best a puzzle and to some jazz historians, they merely contain “some of the stupidest pages ever written about jazz” and are generally dismissed without further comment”.[26]

Jazz during the Cold War

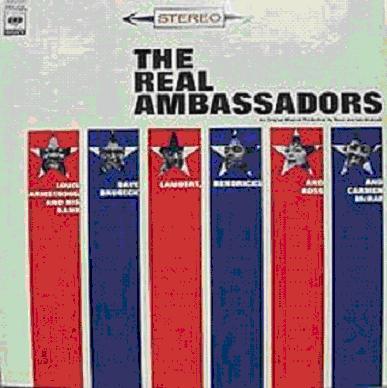

Jazz was also instrumentalized and used by the United States during the Cold War in order to reach different countries and to expand American cultural influence over other societies. For instance, one of greatest names of jazz history and a prominent defender of American liberalism, Dave Brubeck, together with his wife Iola Brubeck started the project of “The Real Ambassadors” in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[27] The Real Ambassadors was born of Dave and Louis Armstrong’s shared belief in equality for all and the utter refusal to tolerate racial discrimination in their own lives. Conceived in 1956, “The Real Ambassadors” took its first steps in 1961, when Dave, Louis and their bands came together with the top jazz vocal group of all time, Lambert, Hendricks and Ross to record the score. It was performed only once in concert version by Dave, Louis and the album cast, at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival and was a smash hit.[28] The project addressed the U.S. Civil Rights movement, the music business, America’s place in the world during the Cold War, the nature of God, and a number of other themes. It was set in a fictional African nation called Talgalla and its central character was based on Armstrong and his time as a jazz ambassador.[29] In writing this work, the Brubecks drew upon experiences they and their friends and colleagues had touring various parts of the world on behalf of the U.S. State Department. The Brubecks and Armstrong (among many other musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington) were part of a campaign by the State Department to spread American culture and music around the world during the Cold War, especially into countries whose allegiances were not well defined or that were perceived as being at risk of aligning with the Soviet Union. Fittingly, “The Real Ambassadors” was about the important role that musicians play as unofficial ambassadors for their countries. Moreover, though intended as a color-blind promotion of democracy, this unique Cold War strategy unintentionally demonstrated the essential role of African Americans in U.S. national culture.[30]

The Real Ambassadors

Tony Shaw, in his book Hollywood’s Cold War (2007)[31], analyzes how Hollywood was instrumentalized by US governments during the Cold War (1945-1990) against the USSR and communism. Shaw thinks that successive American governments thought of winning the hearts and minds of people around the world in order to get more support to USA against the communist ideals of Soviet Russia.[32] Fred Astaire, being light-hearted, nimble-witted, small of voice and light of foot, became the leading star of the era[33], alongside with the jazz music which was thought to be a perfect representation of American liberalism that is based on individual freedoms and free-market economics.[34] Thus, jazz is also used for the spread of American soft power and culture but was welcomed by societies who value art more than politics; because art unified people, whereas politics made them enemy to each other. Jazz was a perfect choice for the U.S.; because unlike the planned Marxist-based command economy of the Soviet Russia, it was based on improvisation which might be resembled to free enterprise and free-market in economic theory.

The Real Ambassadors project was a great success

Conclusion

Jazz music is an American born music type that is political by its very first day. Jazz represented the “chagrin” using French term, pains of disadvantaged groups, most notably African Americans. It also helped African American women and women in general to have a better socioeconomic status and respect. The great success of jazz music directed successive American governments to take advantage of the jazz and to promote it as a way to express American liberalism.

Dr. Ozan ÖRMECİ

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- “8 Mart Dünya Kadınlar Günü`nde caz müziğinde kadınların konumuna tarihsel bir bakış açısı”, Cazkolik, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://www.cazkolik.com/PopulerGundem1/105643/8_Mart_Dunya_Kadinlar_Gunu%60nde_caz_muziginde_kadinlarin_konumuna_tarih.html.

- Angı, Çiğdem Eda (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), pp. 59-81, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://www.idildergisi.com/makale/pdf/1380239033.pdf.

- Arıcı, İsmet (1994), “Güncel ve Popüler Müzik Ders Notları”, Ocak 2014, Marmara Üniversitesi Atatürk Eğitim Fakültesi Güzel Sanatlar Eğitimi Bölümü Müzik Öğretmenliği Anabilim Dalı, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://dosya.marmara.edu.tr/aef/mzo/2013-2014%20duyurular/%C4%B0smet%20ARICI/gpm_2014.pdf.

- Babacan, M. Devrim (2013), “Caz Teorisi Kitaplarının Karşılaştırmalı İncelenmesi”, Eğitim ve Öğretim Araştırmaları Dergisi, Vol. 2, No: 3, August 2013, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://www.jret.org/FileUpload/ks281142/File/28b.babacan.pdf.

- Bernstein, Leonard (1956), “What is Jazz?”, LP Spoken Word Educational, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3DnZ6rG3vI.

- Carney, Courtney Patterson (2003), “Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920s”, A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, December 2003, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-1110103-161818/unrestricted/Carney_dis.pdf.

- “Caz”, Vikipedi, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caz.

- “Caz tarihinin hakkı yenmiş, unutulmuş mimarları… New York`un yeni caz kadınları bu isimleri yeniden yaşatıyor…”, Cazkolik, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://www.cazkolik.com/JazzliGundem/105779/Caz_tarihinin_hakki_yenmis_unutulmus_mimarlari_New_York%60un_yeni_caz_kadinlari_bu_isimleri_yeniden_yasatiyor.html#.

- Farley, Jeff (2008), “Making America’s Music: Jazz History and the Jazz Preservation Act”, A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of American Studies University of Glasgow, July 2008, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://theses.gla.ac.uk/519/1/2008farleyphd.pdf.

- Gushee, Lawrence (1994), “The Nineteenth–Century Origins of Jazz”, Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 14, No: 1, Spring 1994, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://jazzstudiesonline.org/files/jso/resources/pdf/14.1%20Nineteen%20Century%20Origins.pdf.

- Güriz, Haluk (2014), “Adorno ve Frankfurt Okulu”, Haluk Güriz’in Yazıhanesi, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://halukguriz.wordpress.com/2014/01/08/adorno-ve-frankfurt-okulu/.

- “History of Jazz”, Scholastic, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/bhistory/history_of_jazz.htm.

- Howze, Margaret (2016), “Jazz Profiles from NPR Women In Jazz, Part 1”, NPR, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzprofiles/archive/women_1.html.

- Howze, Margaret (2016), “Jazz Profiles from NPR Women In Jazz, Part 2”, NPR, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzprofiles/archive/women_2.html.

- “Jazz”, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jazz.

- “Jazz”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz.

- Örmeci, Ozan (2010), “The Culture Industry and the Critic of Popular Culture by Theodor Adorno”, Ozan Örmeci Makaleler, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://ydemokrat.blogspot.com.tr/2010/10/culture-industry-and-critic-of-popular.html.

- Örmeci, Ozan (2010), “Theodor Adorno”, Ozan Örmeci Makaleler, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://ydemokrat.blogspot.com.tr/2010/08/theodor-adorno.html.

- Penny M. Von Eschen (2006), Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War, Harvard University Press.

- Robinson, J. Bradford (1994), “The Jazz Essays of Theodor Adorno: Some Thoughts on Jazz Reception in Weimar Germany”, Popular Music, Vol. 13, No: 1 (Jan. 1994), pp. 1-25.

- Schuller, Gunther (1996), “Jazz: A Historical Perspective”, The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Delivered at Cambridge University on February 5-7, 1996, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/s/schuller97.pdf.

- Shaw, Tony (2007),Hollywood’s Cold War, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://www.academia.edu/6975392/Hollywoods_Cold_War_PDF.

- “The baseball origin of ‘jazz””, Oxford Dictionaries, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2015/04/jazz-baseball/.

- “The Beginning – Monterey Jazz Festival 1962”, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from http://www.therealambassadors.com/2.htm.

- “The History of Jazz”, A Florentine Films Production, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmypHOyKQ-o.

- “The Real Ambassadors”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Real_Ambassadors.

- Zimmer, Ben (2009), “‘Jazz’: A Tale of Three Cities”, Visual Thesaurus, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.visualthesaurus.com/cm/wordroutes/jazz-a-tale-of-three-cities/.

[1] Here, the reference is made to Nazi Germany (Hitler’s Third Reich) and Soviet Russia (Stalin’s totalitarian Russia), not to today’s Germany or Russian Federation.

[2] For 20 best books about jazz, see; http://www.udiscovermusic.com/20-great-books-about-jazz.

[3] Çiğdem Eda Angı (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), p. 65.

[4] “Jazz”, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Date of Accession: 05.08.2016 from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jazz.

[5] “Jazz”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 05.08.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz.

[6] “The baseball origin of ‘jazz””, Oxford Dictionaries, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2015/04/jazz-baseball/.

[7] “Jazz”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 05.08.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz.

[8] Ben Zimmer (2009), “‘Jazz’: A Tale of Three Cities”, Visual Thesaurus, Date of Accession: 05.08.2016 from http://www.visualthesaurus.com/cm/wordroutes/jazz-a-tale-of-three-cities/.

[9] Çiğdem Eda Angı (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), p. 65.

[10] Çiğdem Eda Angı (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), p. 65.

[11] M. Devrim Babacan (2013), “Caz Teorisi Kitaplarının Karşılaştırmalı İncelenmesi”, Eğitim ve Öğretim Araştırmaları Dergisi, Vol. 2, No: 3, August 2013, p. 234.

[12] Çiğdem Eda Angı (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), p. 66.

[13] ibid.

[14] Leonard Bernstein tried to explain jazz during the Cold War. See; Bernstein, Leonard (1956), “What is Jazz?”, LP Spoken Word Educational, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V3DnZ6rG3vI.

[15] Çiğdem Eda Angı (2013), “Müzik Kavramı ve Türkiye’de Dinlenen Bazı Müzik Türleri”, İdil Dergisi, 2 (10), p. 67.

[16] “Jazz”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz.

[17] For a list of jazz standards, see; http://www.jazzstandards.com/compositions/.

[18] “Jazz”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jazz.

[19] Margaret Howze (2016), “Jazz Profiles from NPR Women In Jazz, Part 1”, NPR, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzprofiles/archive/women_1.html.

[20] ibid.

[21] Margaret Howze (2016), “Jazz Profiles from NPR Women In Jazz, Part 2”, NPR, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.npr.org/programs/jazzprofiles/archive/women_2.html.

[22] ibid.

[23] Taken from Örmeci, Ozan (2010), “The Culture Industry and the Critic of Popular Culture by Theodor Adorno”, Ozan Örmeci Makaleler, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://ydemokrat.blogspot.com.tr/2010/10/culture-industry-and-critic-of-popular.html.

[24] Örmeci, Ozan (2010), “Theodor Adorno”, Ozan Örmeci Makaleler, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://ydemokrat.blogspot.com.tr/2010/08/theodor-adorno.html.

[25] Güriz, Haluk (2014), “Adorno ve Frankfurt Okulu”, Haluk Güriz’in Yazıhanesi, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://halukguriz.wordpress.com/2014/01/08/adorno-ve-frankfurt-okulu/.

[26] See; Robinson, J. Bradford (1994), “The Jazz Essays of Theodor Adorno: Some Thoughts on Jazz Reception in Weimar Germany”, Popular Music, Vol. 13, No: 1 (Jan. 1994), pp. 1-25.

[27] For a website on this project, see; http://www.therealambassadors.com/.

[28] “The Beginning – Monterey Jazz Festival 1962”, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from http://www.therealambassadors.com/2.htm.

[29] “The Real Ambassadors”, Wikipedia, Date of Accession: 06.08.2016 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Real_Ambassadors.

[30] For a book on the project, see; Penny M. Von Eschen (2006), Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War, Harvard University Press.

[31] Shaw, Tony (2007), Hollywood’s Cold War, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, Date of Accession: 18.06.2016 from https://www.academia.edu/6975392/Hollywoods_Cold_War_PDF.

[32] Shaw, Tony (2007), Hollywood’s Cold War, p. 3.

[33] Shaw, Tony (2007), Hollywood’s Cold War, p. 29.

[34] Shaw, Tony (2007), Hollywood’s Cold War, p. 33.

2 Comments »