Preface

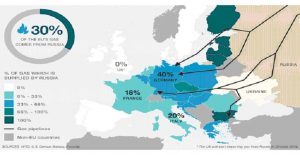

Gazprom is increasing the volume of its deliveries to the European Union. European countries rely on Russian energy and exports to the country. In the meantime, there is an enduring debate if it will soon have to compete with U.S. exporters of cheap shale gas, with the first deliveries of American gas soon due to arrive in Europe or not. Will shale gas creates hazardous impact on Russian company’s market share or not particularly after the announcement of International Energy Agency (IEA)[i] in 2017 concerning the power of US in sense of shale gas? It sounds like an post-apocalyptic drama for Russia. Are geopolitical maneuvers in horizon? In order to grasp the fact and study on consecutive articles pertaining such debate properly, initially we better focus on the dynamics of Europe’s Russian Gas dependency. Hence, this article aims to illuminate the recent facts and issues concerning Europe’s dependency on Russian Gas.

Map: Europe’s thirst for Russian gas

In May 2017, in an interview with Sputnik, Thierry Bros, senior research fellow at Oxford Institute for Energy Studies and founder of thierrybros.com, explicitly focused on the EU’s policy pertaining to Russia, which he said borders on schizophrenia. The interview came after an article published by the Wall Street Journal on Monday said that anti-Russian sanctions had failed to stop sustained growth in the country’s oil industry. In the midst of June 2017, German leaders including German Chancellor Merkel have reacted angrily to proposed new American sanctions on Russia they say target Moscow’s new gas pipeline to Europe[ii], threatening retaliation if the measures harm the European economy. The stand-off comes amid already strained relations with the US over Donald Trump’s aggressive rhetoric and provoked accusations that America was trying to promote its own gas exports to Europe by blocking Russia. The result is a rumbling threat of a new energy war and a breakdown in Trans-Atlantic unity against Russian aggression.

Currently, US intensify its pressure to break Russia’s monopolistic stranglehold over Europe’s energy market. Lithuania became the first former Soviet state to receive a shipment of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the U.S in last week of August 2017. While Lithuania is expected to import another shipment of LNG from the U.S. in September 2017, several other European countries could soon opt to follow suit. As a result, the increased competition in the gas industry could help to drive down prices for European customers.[iii] The deal is aimed to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia’s gas supplies. In July 2017, Poland became the first Eastern European country to receive a shipment of U.S. LNG. Speaking in Warsaw at the time, President Donald Trump said he hoped for stronger ties between the two countries on energy. Following a meeting with the U.S. premier, Polish President Andrzej Duda said he expected to sign a long-term transatlantic deal for LNG supplies, before adding that any such agreement would reduce Warsaw’s reliance on Russian “blackmailing. Some central and east European countries especially Poland and Lithuania might prefer to import U.S. LNG and pay a higher price because they made reduction of dependence on Russian gas one of their main political priorities as they see it as a security issue,” Katja Yafimava, a London-based analyst at the Oxford Energy Institute, told CNBC via email. Yafimava explained that while current price levels meant Russian gas is competitive with U.S. LNG for European buyers, Moscow would likely adopt a strategy to “dis-incentivize” a second wave of LNG from the other side of the Atlantic over the next decade. Snowballing shipments of U.S. natural gas have been made possible by the shale revolution in the country. And the world’s prevalent economic and military power is now seeking to peel away business from Russian gas companies, such as state-backed energy giant Gazprom.

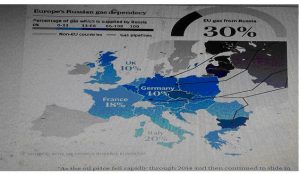

Russia’s share of EU-28 imports[iv] of natural gas declined from 34.6 percent to 26.8 percent between 2005 and 2010, but this development was reversed and a relative peak of 32.4 percent was recorded in 2013, after which the share fell somewhat to just below 30.0 percent European dependence on oil imports has grown from 76 percent in 2000 to over 88 percent in 2014. The EU spends some €215 bn on oil imports, over 5 times as much as gas imports (€40 bn). Russia is the biggest supplier: dependence on Russia has grown from 22 percent in 2001 to 30 % in 2015. Within the same year, on April 22nd, 2015 the European Union (EU) filed antitrust charges against Russian gas giant Gazprom, the world’s largest producer, for abuse of market power. Amongst the allegations are that Gazprom willingly manipulated and put undue pressure on countries to use Gazprom’s infrastructure exclusively, and, pursued an overall strategy to partition central and eastern European gas markets. These are some of the main conclusions of a study from Cambridge Econometrics made for the Brussels-based NGO Transport & Environment (T&E). According to “A Study on oil dependency in the EU”, published on 11 July, since 2000, there has been a gradual decline in total final consumption of oil and petroleum products in the EU (on average a 1.1 % reduction per annum). At year-end 2015, Gazprom saw its share in the European market rise from 30 to 31 percent. This slightly more than 3-percent growth may appear modest, but this is the first evidence of Russian gas increasing its presence in Europe, which has been actively diversifying its energy consumption over the past 10 years.[v] In addition, the company’s growth in individual countries looks much more impressive. It is as much as 37 percent in France, 17 percent in Germany, 12.6 percent in Italy, and 10 percent in the UK.

The debate over the Nord Stream 2 project, the projected gas pipeline that will run through Finland, Denmark, Sweden and Germany to connect Russia and the EU, has been revived. For further elucidation, the pipeline passes through the territorial waters and/or Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. The project’s managers are also holding consultations with Poland, which has expressed opposition to the project, as well as the neighboring Baltic states. After it firstly appeared that the EU might attempt to block Russia’s new pipeline project, there were tentative signs that opposition to it may be softening in July 2016 just before access to the OPAL pipeline had been temporarily deferred. As Jens Mueller, a spokesperson for the Nord Stream project, pointed out on July 6, “We do not see the European Union’s pressure on the four countries – Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Finland, whose exclusive economic zones will be used for the installation of the pipeline. “We know that it is necessary to fulfil all the requirements of EU legislation. We do not feel the EU Commission’s intention to block the project, [we just see] its intention to make it [the project] comply with the relevant EU laws.” [vi] based on the news Russia Direct.

Actually, the dispute over the Nord Stream 2 pipeline has its origins in the evolution of Russia’s gas export strategy over the past decade. Since 2006, when the first interruption of Russian gas transiting Ukraine occurred and provoked the gas war between Russia and Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has been adamant that avoidance of any transit intermissions should be a key plank of Gazprom’s strategy in Europe. [vii] Such view was confirmed in 2009, when the most serious interruption of supply to date occurred as a result of a second dispute with Ukraine over gas prices and supply, and this event catalyzed the construction of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. The European Commission (EC) and European Union (EU) member states gave a vigilant welcome to the extra 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) of pipeline capacity through the Baltic Sea, as it provided additional security of supply in the event of transit disruptions elsewhere. So, Nord Stream 2 will comprise a twin 1,200 km pipeline with a capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas. It will run underneath the Baltic Sea from the Russian town of Vyborg near the Finnish border to Lubmin, near Greifswald in Germany. The construction runs roughly parallel to the existing Nord Stream pipeline, which began operating in 2011. In 2016, the Nord Stream Pipeline operated at 80 per cent of its annual capacity of 55 bcm, delivering 43.8 bcm of natural gas to consumers in the EU.[viii]

Nevertheless, from a Russian perspective, it was clearly not the ultimate answer, as some reliance on Ukraine remained. Total pipeline export capacity to Europe from Russia amounts to around 240 bcm, with 120 bcm passing through Ukraine. With Gazprom exports averaging 150-160 bcm, it is clear that at least 30-40 bcm of this must use the Ukrainian system. In response to this problem, Gazprom consequently planned a second direct pipeline route, South Stream, via the Black Sea to Bulgaria. With 63 bcm of capacity, this pipeline could have allowed Gazprom to avoid Ukraine altogether, completely changing the dynamics of its trade with Europe. However, in December 2014 the South Stream pipeline was cancelled after tensions related to the Ukraine crisis.[ix]

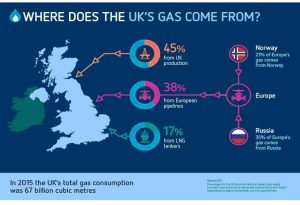

Russia’s state-backed gas company reported higher gas sales to Europe again last quarter as energy importers continue to extend their dependence on the gas giant.[x] Gazprom’s sales ascended by 4.4pc to R1.8tn ($31bn) in the first three months of the year (2017) as the appetite for gas grows within Europe and the former Soviet Union. Although the UK does not directly import gas from Russia, Gazprom’s largest European customers are in Germany and the Netherlands, which are closely connected to the UK gas grid through two major pipelines. Russian gas volumes sold by the Kremlin-controlled company to Europe and some neighboring countries grew by 13pc in the first months of 2017 to 65.6 billion cubic meters. According to market specialists at Icis the amount of Russian gas that flowed into the European gas grid, excluding Baltic states, reached 42.3 billion cubic meters in the first quarter, well above the 37bcm in the same quarter last year(2016) and 25.8bcm in the first months of 2015. Gazprom’s strong quarter for exports began with an all-time daily high in the first week of the year. The gas giant pumped a record 615.5 million cubic meters of gas to countries outside the former Soviet Union on January 6 amid a cold snap across Europe. Demand for Russian gas is on the rise in part because North Sea supplies are dwindling and power generators are increasingly burning gas for electricit.

In the UK, the steady shutdown of coal-fired power plants has allowed gas-fired power to become the dominant power source once again after a few years in which coal was in the ascendancy. France has also increased its use of gas power following the decision to shut down a string of nuclear reactors after a fault was detected in a widely-used reactor design. The lower price for gas is also playing a role in Europe’s increasing reliance on Russian imports, according to Jake Horslen, a European gas market specialist at data provider Icis. “The price at which Gazprom sells its gas to Europe is linked to oil products – normally with a six to nine month time lag – which means that developments in the oil market often determine how economic the gas is for European buyers,” he said.

The provisional measures constraining the use of OPAL pipeline have been lifted

Despite this, Alexander Khrushudov from the Oil and Gas Information Agency told RT that OPAL and Nord Stream should not be subject to the jurisdiction of the Third Energy Package of directives, which aims to create a single, regulated gas and electricity market in the EU. In the beginning, OPAL was built jointly by Germany and Gazprom with the permission of the EU Commission. It was stipulated that as a continuation of ‘Nord Stream 1’ it doesn’t fall under the jurisdiction of the Third Energy Package,” Alexander Khrushudov from the Oil and Gas Information Agency told RT.

In late July, the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf has repealed its decision dated December, 30, 2016, according to which the effect of a Settlement Agreement concerning the access to the OPAL pipeline had been temporarily suspended. Earlier, on July 21, 2017, the General Court of the European Union has rejected the request of PGNiG S&T GmbH, PGNiG S.A., and the Republic of Poland regarding the interim measures, and repealed its earlier decision which was temporarily suspending the effect of the Decision of European Commission dated October, 28, 2016, on the use of the OPAL pipeline capacities. The OPAL (Ostsee-Pipeline-Anbindungsleitung) is a natural gas pipeline in Germany alongside the German eastern border. The Decision of the European Commission of October, 28, 2016 and the Settlement Agreement of November, 28, 2016 hereby remain valid. This would allow the company-operator of the OPAL pipeline to held auctions for OPAL capacity booking after receiving the corresponding approval from the German regulator, and allow Gazprom Export and interested third parties to participate in these auctions and book capacities within them.[xi]

Reuters headlined the news “EU court rejects Polish bid to halt Opal pipeline deal, verdict in 2019. According to A European Commission deal giving Gazprom (GAZP.MM) a bigger share of the Opal gas pipeline can go ahead for now until a ruling is issued in 2019, Europe’s second-highest court said on July 21st in a rejection of a Polish bid to halt the move. The EU executive’s decision lifting the cap on Russian state-controlled Gazprom’s use of the pipeline in October last year, referring 2016 angered Poland as it would erode the country’s role as a transit site and its influence in future gas supply talks.

The pipeline carries gas from the Nord Stream pipeline under the Baltic Sea to customers in Germany and the Czech Republic. The Luxembourg-based General Court suspended the EU decision in December 2016 following a challenge by Poland, state-run gas firm PGNiG PGN.WA and PGNiG Supply & Trading. The plaintiffs said Gazprom’s increased gas transports via Opal would result in less gas for two other pipelines, threatening Polish gas supply. Court President Marc Jaeger said he was revoking the suspension because there was no proof of serious harm. “The applicants have failed to show that the harm suffered as a result of the contested decision is serious and irreparable and therefore that decision remains applicable until delivery of the judgments on its lawfulness,” he said. “In the light of the average duration of proceedings before the General Court, the judgments on the substance in the present cases will probably be delivered during 2019.” Gazprom supplies about a third of Europe’s gas needs noted as well.

On the basis of the figures below, Western Europe and Central Europe supplies diverges.

Gas supplies to Europe

Natural gas exports made to countries outside the former Soviet Union by Gazprom Export (billion cubic meters)

| Year | 1973 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016 |

| Total | 6.8 | 19.3 | 54.8 | 69.4 | 110.0 | 117.4 | 130.3 | 154.3 | 138.6 | 158,6 | 178,3 |

In 2016, Gazprom Export supplied 178.3 billion cubic meters of gas to European countries. Western European countries accounted for approximately 80 % of the company’s exports from Russia, while Central European states took 20 %.

The Western European market (including Turkey) consumes the bulk of Russian exports. In 2016, Gazprom Export delivered 146.2 billion cubic meters of gas to markets in the region

| Austria | 6.08 |

| Denmark | 1.75 |

| Finland | 2.53 |

| France | 11.47 |

| Germany | 49.83 |

| Greece | 2.68 |

| Italy | 24.69 |

| Netherlands | 4.22 |

| Switzerland | 0.31 |

| Turkey | 24.76 |

| United Kingdom | 17.91 |

The Eastern and Central European natural gas market is particularly important because of its geographical proximity to Russia. The Russian “blue fuel” accounts for more than a half of gas consumption in the region. In 2016, Gazprom Export sold 32.1 billion cubic meters of gas in this market:

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.22 |

| Bulgaria | 3.18 |

| Czech Republic | 4.54 |

| Hungary | 5.54 |

| Macedonia | 0.07 |

| Poland | 11.07 |

| Romania | 1.48 |

| Serbia | 1.75 |

| Slovakia | 3.69 |

| Slovenia | 0.52 |

Conclusion

The option of importing U.S. LNG a kind of mechanism for negotiating new long- and short-term prices with other suppliers. Surely it’s the power and logic of the negotiation in the emerging competitive environment. Some central and east European countries especially Poland and Lithuania might prefer to import U.S. LNG and pay a higher astronomic price because they made reduction of dependence on Russian gas one of their main political priorities as they see it as a security issue, So regardless of opposition from Poland and Ukraine, the EU Commission is unlikely to stop the Nord Stream 2 project since it enables the bloc to achieve its clean energy objectives. In the meantime If U.S. LNG delivered into Europe is steadily higher priced than Russian gas, the trade will not be feasible and sustainable.

Besides, according to opinion leaders, the Nord Stream 2 project provides the EU Commission an opportunity to implement its “Energy Union” strategy, which was adopted in February 2015 and aims to provide Europe with secure, affordable and climate-friendly energy. Importing more gas from Russia is necessary for the EU since reserves in the EU and Norway are depleting, while proliferation of gas consumption is expected over the next few decades. In the light of the facts, issues and opinions; although Europa is seeking for alternatives, the revolutionary change to unchain “Russian gas dependency and vulnerability for Europa” is not so near. EU energy importers seems to extend their dependence on the gas giant namely Russian Federation for the now being.

H. Çiğdem YORGANCIOĞLU

[i] Çiğdem Yorgancıoğlu, “Dünya Petrol Kongresi’nde Kayagazıyla Enerji Devrimine Dokunuşlar”, Uluslararası Politika Akademisi (UPA), 17 July 2017, http://politikaakademisi.org/2017/07/17/22-dunya-petrol-kongresinde-kayagaziyla-enerji-devrimine-dokunuslar/.

[ii] “Germany threatens retaliation if US pushes ahead with Russia sanctions it says could harm European economy”, The Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/16/germany-threatens-retaliation-us-pushes-ahead-russia-sanctions/.

[iii] Sam Meredith, “US ratchets up pressure to break Russia’s stranglehold over Europe’s energy market”, CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/23/us-pressures-russias-stranglehold-over-europes-gas-market.html.

[iv] EC Europa EU Eurostat Statistics Energy Production and Imports, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Energy_production_and_imports.

[v] Russia Direct, http://www.russia-direct.org/russian-media/europe-become-energy-battlefield-between-russia-and-us.

[vi] Russia Direct, http://www.russia-direct.org/opinion/unclogging-political-issues-blocking-russias-nord-stream-2-pipeline.

[vii] Çiğdem Yorgancıoğlu, “Neşvu nema Trblansta Rövaşata”, Uluslararası Politika Akademisi (UPA), 7 January 2015, http://politikaakademisi.org/2015/01/07/nesvu-nema-turbulansta-rovasata/.

[viii] Sputniknews, https://sputniknews.com/europe/201704031052232006-nord-stream-eu-gas-pipeline/.

[ix] Çiğdem Yorgancıoğlu, “Güney Akım Projesinin İptali Nedenleri Üzerine”, Uluslararası Politika Akademisi (UPA), 19 January 2015, http://politikaakademisi.org/2015/01/19/guney-akim-projesinin-iptal-nedenleri-uzerine/. Çiğdem Yorgancıoğlu, “Pse është anuluar projekti (South Stream ) Linja Jugore”, Media E Lire, http://www.mediaelire.net/lajm/2361/pse-eshte-anuluar-projekti-south-stream-linja-jugore.

[x] Jillian Ambrose, “Gazprom continues to grow dominance in European gas”, The Telegraph, 31 May 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2017/05/31/gazprom-continues-grow-dominance-european-gas.

[xi] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-gazprom-europe-gas-court-idUSKBN1A625Z.

One Comment »