Introduction

Ofra Bengio’s book Türkiye Israel: From Phantom Alliance to Strategic Cooperation (Türkiye İsrail: Hayalet İttifaktan Stratejik İşbirliğine) draws attention to how Israel’s official views on Türkiye have been shaped in time. According to the author, Israel values the fact that Türkiye is one of the few countries in the region that officially recognized it years ago (Türkiye was the first Muslim-majority country to recognize Israel in 1949) and therefore wants to develop strategic, political, and diplomatic relations with Ankara. Israel, a country that has been ostracized by the Muslim states in the region since its establishment, therefore wants to strengthen its relations with Türkiye to reinforce the process of normalization and acceptance of its presence in the region. For this reason, initiatives to improve relations with Türkiye usually come from Israel. Israel takes Türkiye’s sensitivities seriously and endeavours to be attentive to issues that may cause discomfort in Ankara.

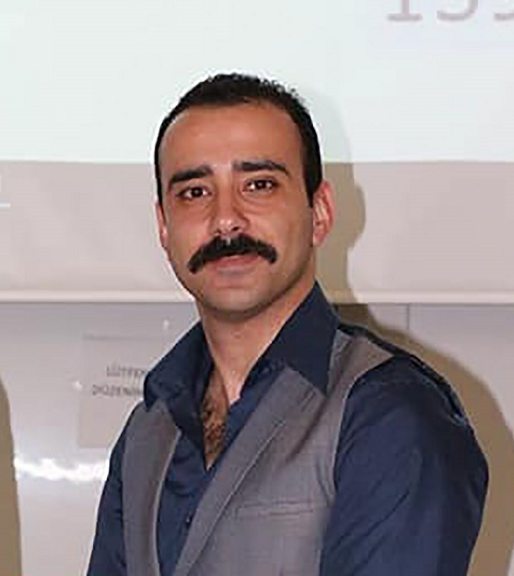

Ofra Bengio

According to Ofra Bengio, Türkiye, on the other hand, sees a strategic opportunity in its relations with Israel, but at the same time is careful not to let it negatively affect its relations with the Arab states. In this context, according to the author, four basic rules shape Türkiye’s behaviour in its relations with Israel:

- The need to adopt a position of balance vis-à-vis Israel and the Arab states,

- The assumption that the nature of relations with Arab countries depends almost entirely on the type of relationship with Israel,

- The view that establishing friendly relations with Israel could lead to a rupture in relations with the Arabs,

- Türkiye’s desire to maintain its ties with Israel, but to be discreet about it.

Türkiye Israel: From Phantom Alliance to Strategic Cooperation (Türkiye İsrail: Hayalet İttifaktan Stratejik İşbirliğine)

Part One: After the 1991 Gulf War Earthquake

With the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq led by Saddam Hussein, the United States (U.S.) President George H. W. Bush took action to establish the “New World Order”. Starting from this period, the U.S. rapidly increased its military presence in the Middle East in terms of quantity and quality. The Gulf War brought 532,000 American troops (plus 760,000 troops of other nations), 2,070 tanks, 1,376 fighter planes, 1,900 helicopters, and 180 ships to the region. Although on paper 28 countries participated, the U.S. undoubtedly bore the brunt of the Gulf War. In the end, Iraq was expelled from Kuwait, but Saddam Hussein’s regime remained intact. Moreover, Saddam’s regime became even more dangerous for its neighbours and the Kurdish and Shiite communities. Therefore, the U.S. began to justify its presence in the Middle East with the argument of protecting these vulnerable groups. This is the Idealism part. There is also a strong Realism argument supporting it, which is the U.S. desire to control Middle Eastern oil and to end the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Two factors facilitate the U.S. in this process. The first is the inability of the collapsing Soviet Union to send troops to the region. Secondly, the local actors/powers of the region, such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, decided to support and align with the U.S. policies. This prevented the Gulf War from turning into a new Vietnam War (1955-75) and a second Vietnam syndrome.

The Gulf War was a real turning point in the history of the United States because until then, the United States had never gone to war with any country in the region. In the course of this war, the U.S. began to build its military strategic interests in the regional equation alongside its oil interests in the region. In this process, the U.S. tried to fill the power vacuum created by the United Kingdom, which lost its power in the region in the 1970s, and the Soviet Union, which became ineffective in the region in the 1990s. However, Washington also began to face contradictions and difficulties in the region.

First of all, the U.S., which initially did not want to get involved in Kurdish and Shiite politics, found itself more and more involved in these policies as the years progressed and gradually increased its support for the Kurds, especially starting from the Bill Clinton era. From 1996 onwards, the U.S. began to play a mediating role between the two rival Kurdish groups in Northern Iraq, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) led by Massoud Barzani and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) led by Jalal Talabani, and hosted representatives of both movements in Washington. While trying to overthrow Saddam’s regime, the U.S. also opposed the partition of Iraq, which led to contradictory policies. As a result, since the Gulf War, Iraqi Kurds gained de facto autonomy north of the 36th parallel.

Although it was Republican President Bush (Bush Sr.) who came up with the idea of a New World Order, it was Democratic President Bill Clinton who concretized it. The principles of this policy, concretized during the Clinton era, were articulated by Martin Indyk, the senior director for Near East and South Asia at the National Security Council. This policy can be summarized under the following headings:

- The U.S. will no longer view the region through a global prism based on competition and will assess changes there according to the impact of U.S. regional, rather than global, interests.

- Having become the undisputed dominant power for the first time, the U.S. is now willing to use its influence in the region.

- The region can no longer be viewed in fragmented terms due to factors such as the rise in the number of ballistic missiles and the spread of religious extremism.

- In parallel with Türkiye’s growing regional role, the newly established Muslim states in Central Asia should be given new roles.

Martin Indyk summarizes the U.S.’ abiding interests in the region in four main principles: (1) the free flow of oil at favourable pricing, (2) support for Arab countries that want to get along with the U.S., (3) ensuring Israel’s security and prosperity, and (4) resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict. In this sense, a regional policy based on the bilateral containment of Iraq and Iran aims to offer a more democratic and prosperous vision for all the peoples of the Middle East. However, while significant progress has been made in this policy, the mullah regime in Iran has not been overthrown and the anti-American power structure in Iraq under the control of Saddam Hussein and his Ba’ath Party continues.

With the end of the Cold War, Türkiye faced a significant challenge and opportunity at the same time. Although the end of the Cold War led to Ankara’s loss of importance in the absence of the Soviet threat, the Gulf Crisis and Türkiye’s role in reaching out to the Turkish and Muslim population in Central Asia increased the country’s importance once again. Ankara’s Cold War principle of non-interference in regional affairs and internal affairs had to change in this new era. This is a natural consequence of the reflection on the foreign policy of a country that is more integrated into the West. Indeed, during the Cold War, Ankara demonstrated a pro-Western policy in the region with initiatives such as its participation in the 1955 Baghdad Pact and the secret Peripheral Pact with Israel in 1958. However, from the 1960s onwards, Türkiye also turned to a policy of diversifying its relations with the West due to the Cyprus Problem and endeavoured to improve its relations with the Soviets and the Arab states in the region. In this process, Ankara became a member of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (now Islamic Cooperation Organization) and its sensitivity to the Palestinian Question increased significantly. In the 1990s, Türkiye, concerned about its loss of importance in the West, was also disturbed by the Armenian Genocide bills that came to the agenda in the U.S. and European countries. In this environment, it became a rational policy for Ankara to improve relations with Israel, which had strong relations with the West and especially with the U.S.

Part Two: A Past Future-Environment Alliance

In 1958, Türkiye and Israel established a secret Peripheral Pact or Peripheral Alliance (Çevresel Pakt) called the “Ghost Pact” or “Ghost Alliance” (Hayalet Paktı/İttifakı). Although Iran (the Shah’s regime) and Ethiopia (Abyssinia) were also part of this pact, this work analyzes this process from the perspective of Türkiye and Israel.

The concept of the Peripheral Alliance was first articulated by Baruch Uziel in a series of lectures given before the establishment of the State of Israel. At its core, the concept is based on rapprochement with non-Arab ethnic groups in the region in the face of a large Arab confederation or empire that could impede Israel’s existence and access to the sea. In this context, Turks inside and outside Türkiye, Maronites in Lebanon, Alawites in northern Syria, Greeks, Armenians, Armenians, Kurds, Assyrians, and Iranians (Persians) are the natural non-Arab allies that Israel could have in the region. Uziel’s ideas came to the fore about a decade later when the Turkish-Israeli alliance or the Ghost Alliance was being formed. From day one, Israel had three main concerns: (1) not being seen as legitimate by its Arab neighbours, (2) being excluded by its geographical neighbours, and (3) lacking a strong security presence. Therefore, Israeli decision-makers set several main diplomatic goals. These are: legitimacy, peace and security, trade promotion, foreign approval for its positions, foreign approval for its decisions and institutions, and strengthening ties with world Jewry.

However, realizing that this would not be easy in a short period of time, Israeli decision-makers formulated their relations with the countries in the region on the basis of intelligence and in a more secretive manner, rather than open alliance relations that could put the governments in a difficult situation in front of the public. In this context, especially the name Reuven Shiloah made significant contributions to the establishment of secret alliance relations with Türkiye. During this period, Shiloah calculated that the threat from the pro-Soviet Syrian government would bring Ankara and Tel Aviv (Jerusalem) closer. In this context, it was decided that Israel’s Ambassador to Italy, Eliyahu Sasson, who had previously served in Türkiye, would establish direct contact with Prime Minister Adnan Menderes.

About a year later, the alliance came into effect. However, this process was extremely painful. Türkiye (Menderes administration), which attached more importance to the Baghdad Pact, was not very keen on improving relations with Israel. In response, Moshe Alon, Israel’s Charge d’Affaires in Ankara, emphasized the necessity of influencing Menderes through the United States. In addition, there was a need to establish cooperation at the economic and military-industrial levels and to create a public opinion in Türkiye that was friendly to Israel. In addition, Iran, a Western ally at the time and similarly concerned about the ambitions of the Soviet Union and Egypt in the region, was also instrumental in convincing Ankara to join the Phantom Alliance. The developments in Iraq during this period also began to make Türkiye consider the Phantom Alliance more important than the Baghdad Pact. Developments such as Iraq’s voting against Türkiye in the vote on Cyprus at the United Nations in December 1957, the merger of Syria and Egypt to form the United Arab Republic in 1958, and the fall of the monarchy in Iraq in July 1958 led Türkiye to think that Iraq might not be so enthusiastic about the Baghdad Pact and that Baghdad preferred its loyalty to the Arabs over the Baghdad Pact. In this environment, the Türkiye-Israel alliance regained importance. Within Türkiye, the opposition against the Democrat Party and Menderes, which had been pushing his policy of cosying up to the Arabs to a harsher level.

On top of this, the fact that the United Arab Republic, which was established as a result of the merger of Egypt under the leadership of Gamal Abdel Nasser with Syria, was bordering Türkiye and the new state adopted a foreign policy close to the Soviets like Egypt, created a new geopolitical equation in which Türkiye was surrounded by Russia from the north and the United Arab Republic (Egypt) from the south. In this environment, when Ankara became convinced that Iraq would not adhere to the Baghdad Pact after the coup d’état, a favourable environment for an alliance with Israel was created.

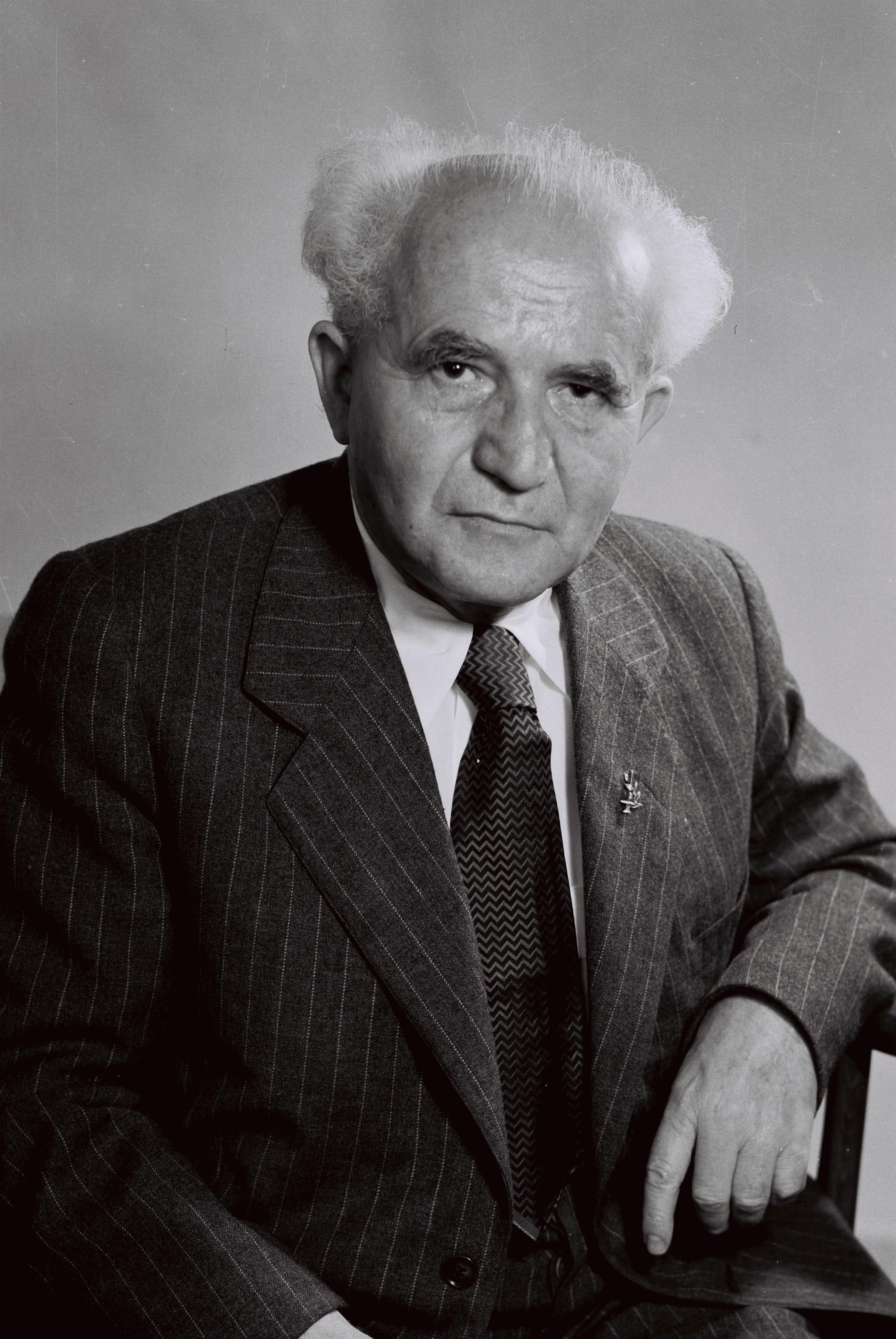

However, it is useful to look back a bit before that. After Türkiye officially recognized Israel on March 28, 1949, the two sides established diplomatic missions in Ankara and Tel Aviv, and relations progressed smoothly until the Baghdad Pact. However, with Türkiye’s accession to the Baghdad Pact, Ankara began to pursue a policy closer to Baghdad. The 1956 Suez Crisis and War triggered this process and Türkiye recalled its ambassador to Israel. Israel responded with a similar move. Since then, Israel has been trying to restore relations. Tel Aviv was convinced that the way to do this was through Washington. From then on, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion would take the lead.

David Ben-Gurion

Ben-Gurion had three main ideas for launching the Periphery Alliance:

- To break the circle of isolation of Israel by Arab countries through alliances with surrounding non-Arab countries,

- Creating a new balance of power to stabilize the region,

- To strengthen relations with the West, especially with the United States.

Israel’s relations with the United States were not very strong at the time and Prime Minister Ben-Gurion wanted to increase his prestige in the eyes of President Eisenhower with this initiative. Ben-Gurion wanted to present this as an initiative that would advance Washington’s interests in the region. The highly secret meeting between Ben-Gurion and Menderes on August 29, 1958, laid the foundations of the Turkish-Israeli alliance. Initially, the Israeli Prime Minister considered Ankara to be the “weak link” in the alliance, since Türkiye, a NATO member, was heavily supported by the United States (at the time there were some 65 American military bases in Türkiye) and was more committed to the Baghdad Pact. The Ben-Gurion-Menderes meeting was followed by many meetings and secret contacts. The most important negotiators on the Israeli side during this period were Foreign Minister Golda Meir, Foreign Ministry political advisor Reuven Shiloah, and Israeli Ambassador to Rome Eliyahu Sasson. Especially in the Golda Meir-Fatin Rüştü Zorlu meetings, the parameters of the alliance were established.

There are four main differences between the Peripheral Pact and the Baghdad Pact.

- The Peripheral Pact was secret and remains secret in many aspects.

- Because of this secrecy, it did not lead to a counter-alliance like the Baghdad Pact.

- Ben-Gurion envisioned a trilateral or multilateral alliance, which turned into bilateral agreements with three individual countries – Ethiopia, Iran, and Türkiye. Nevertheless, in some areas, there was also multiple cooperation.

- Perhaps because it was covert and essentially bilateral, this alliance outlasted the Baghdad Pact.

According to Ofra Bengio, there is a big difference and asymmetry between the Turkish and Israeli versions of the Menderes-Ben-Gurion agreement. The Turkish side has been silent on this issue for years. It is also difficult to find sources on this issue in Türkiye. Generally, the Turkish side is of the view that only an agreement was reached between the two countries on this issue. However, both sides acknowledge that this meeting was a turning point in terms of intelligence exchange. Sezai Orkunt, the head of the Military Intelligence Department between 1964 and 1968, claimed that only ten military and civilian officials knew about this agreement. Türkiye’s secretive attitude on this issue is interpreted as an indication of its extreme sensitivity to not offending the Arab states. Although the veil of secrecy and mystery on this issue has not yet been completely lifted, a consensus has emerged on several issues. First of all, Haggai Eshed’s book on Reuven Shiloah -Shiloah personally participated in the Menderes-Ben-Gurion meeting- states that the representatives of the two sides drew up a list of areas of cooperation and approved it item by item. Eshed wrote that the agreement included cooperation on diplomatic, military, and economic levels. In the diplomatic sphere, there will be joint public relations campaigns involving both governments and public opinion. In the economic field, it was agreed to increase trade and contribute to Türkiye’s industrial development. Finally, at the military level, an agreement was reached on the exchange of intelligence and information, as well as joint planning for mutual assistance in emergencies. Türkiye also promises to support Israel’s request to strengthen its armed forces, both at the Pentagon and NATO. Another Israeli researcher has suggested that the agreement also includes clauses on scientific cooperation and the export of Israeli military equipment to Türkiye. In this context, the Israeli side tends to interpret this initiative as an “alliance” rather than an agreement or a memorandum. Moshe Sasson often used the word “periphery” in his reports from Ankara, and over time phrases such as “Peripheral Alliance”, “Peripheral Pact”, and “Ghost Alliance” came to describe the initiative.

In the intelligence dimension, it would be more accurate to talk about a trilateral alliance. As a matter of fact, in a CIA report, the Americans mention an organization called “Trident”, which was established jointly between Israel-Türkiye-Iran. This organization was established for intelligence cooperation between the MİT – Turkish National Intelligence Agency (then known as MAH – National Labor Service), the Israeli intelligence service Mossad, and the Iranian intelligence service SAVAK. In fact, the heads of the three services meet twice a year. Israeli military attaché Baruch Gilboa, on the other hand, preferred to narrowly interpret the extent of this alliance as Türkiye opening its airspace to Israeli planes using its airspace to fly to Iran.

During the Peripheral Alliance process, the Turkish-Israeli rapprochement officially lasted for eight years, with ups and downs, mainly due to fluctuations on the Turkish side. Israel’s expectations in its relations with Türkiye are constant: Since Israel is shunned by its Arab neighbours, it wants to improve its relations with Türkiye in order to gain legitimacy and avoid isolation. Türkiye’s expectations, on the other hand, are more tactical; Ankara needs a strong Israel to keep Pan-Arabism and Pan-Islamism (Islamism) in check but also seeks Israeli support on issues such as relations with the U.S. and Cyprus. Moreover, while on the Israeli side, all sides support an alliance with Türkiye – when Israel was first established, far-left elements such as Mapam and the Communist Party were not favourable to Türkiye – in Türkiye, this issue becomes more complex, contradictory, difficult, and secretive due to the Islamist-nationalist groups in Anatolia. For this reason, Israel is the party that is more interested in this alliance, while Tel Aviv tries to respect Türkiye’s sensitivities on many issues involving Kurds, Armenians, and Arabs.

In 1958, the issues that brought the two states to the alliance stage can be listed as (1) standing against Soviet expansionism, (2) curbing Pan-Arabism and Pan-Islamism (Islamism), and (3) combating terrorism. As a fourth element, Türkiye and Iran’s efforts to establish close relations with Israel to improve their image in the West can also be added to this list.

The Peripheral Pact continued to strengthen under General Cemal Gürsel, the 4th President of Türkiye, who came to power after the military coup of May 27, 1960. In his August 15, 1960 meeting with Fischer, Gürsel described Turkish-Israeli relations as “an important bastion of stability, peace, development, and progress in the region”. However, despite all this positive atmosphere, Türkiye did not even fully improve its diplomatic relations with Israel. This causes a kind of disappointment in Israel. The Turkish side often uses the argument of not offending the Arab states in this regard. This argument is not without merit, as at the time, the Arab states were pressuring Türkiye to cut its relations with Israel. Moreover, at the end of the Menderes period, in 1959, Türkiye was going to raise its relations with Israel to the level of an embassy, but at the last minute, it decided against it to prevent the Iraqi government of Abdulkarim Qassim from steering the course of the United Arab Republic and the Soviet Union. In addition, Menderes postponed his promised visit to Israel to Ben-Gurion and could not be persuaded by the Israelis. According to the impressions of Israeli officials at the time, it was Foreign Minister Fatin Rüştü Zorlu who prevented Menderes from fully restoring relations during this period. In the end, however, both leaders were overthrown by the May 27 coup d’état.

A similar trend was observed during the Cemal Gürsel era. Although Gürsel stated that he was in favour of improving relations with Israel, politically he was not very enthusiastic about it. The reason is obvious; the Shah of Iran, who normalized relations with Israel, was isolated by the Arab world, especially Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nevertheless, Gürsel improved relations with Israel on many levels on the condition of secrecy. Gürsel’s desire for secrecy was mostly due to the Iraqi factor.

Prime Minister İsmet İnönü, who took office with the coalition in 1961, was also not very assertive in this regard. Although he was the one who initiated relations with Israel in 1949, İnönü had to leave office in 1965 without fulfilling his promise to improve relations. İnönü’s main reservation on this issue was the Arab reaction, especially Iraq. In fact, the situation was so grave that when İnönü offered condolences to Israeli Prime Minister Izak Ben-Zvi after his death in 1963, an Iraqi newspaper attacked him with the following words: “The old man who stabbed the Arabs in the back went to mourn over the grave of a dog”.

Over time, the Arab factor became increasingly important in the agenda of Turkish-Israeli relations and the priorities that led to the establishment of the Turkish-Israeli alliance became less influential due to the growing Arab influence. As a matter of fact, by the end of 1963, Ankara was on a path to improve its relations with four possible sources of threat: the Soviet Union, Iraq, Syria, and Egypt. In this context, the dissolution of the United Arab Republic in 1961 was an important turning point. Türkiye recognized Syria even before the Arab states and in reaction, Egypt severed relations with Ankara for two years. Over time, however, relations with Egypt also improved. Therefore, in the following years, despite promises from Türkiye to improve relations, the Israeli side had to concentrate more on not breaking them. On the other hand, the deepening of economic cooperation lessens the impact of Israel’s disappointment. Both sides have always been keen on economic relations. For example, as early as 1959, Süleyman Demirel, then Director General of the State Hydraulic Works, visited Israel and, impressed by Israel’s success in producing irrigation pipes, advised the Turks to emulate the Israeli people. After coming to power in 1965, Demirel was more balanced in his relations with Israel, but by the 1990s he was in a position to establish an open alliance with Israel.

One important area where bilateral relations have been positive has been agriculture. Israel is endeavouring to export its expertise in this field to Türkiye to present itself well to traditional Muslims who are less favourably disposed towards Israel. It is almost certain that the Israelis who reside in the villages and educate the people will change the perception of Israel among religious people positively. Indeed, in the Adana region, where Israeli methods were implemented, cotton yields quadrupled within six years. The Turkish Ministry of Rural Affairs saw this as a major Turkish achievement and sent hundreds of Turkish officials to Israel for training.

In the first months of 1965, the volume of trade between the two countries reaches 30,000,000 dollars annually for the first time. Apart from agriculture, other important areas of the economy include joint research projects, joint industrial projects and tourism. Israeli experts were even involved in the planning phase of the Keban Dam. Türkiye is eager for economic relations, but not willing to pay the political price as the Arabs are increasingly turning oil into a weapon against Israel and the West. Moreover, there is a growing Arab market. Therefore, far from improving relations with Israel, more serious crises began to emerge between the two countries over time.

Türkiye-Israel relations are strategic because of the threats that compel the two countries to act jointly. In fact, relations at all other levels depend on this strategic partnership. However, since both Turkish and Israeli sources are not clear on this issue, we have to be content with secondary sources. Although the Turkish-Israeli alliance was established by civilians, military cooperation constitutes the most important dimension of the relations. The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) are very keen to develop these relations and are generally more favourable towards Israel than the public and other elites. The TSK is also uncomfortable with the amount and approach of U.S. support to Türkiye (finding it insufficient), and values relations with Israel as a strategic element in terms of alliance with the U.S. Moreover, Israel is a generous country towards its allies in terms of technology sharing (transfer). As a matter of fact, a report by Refik Tulga, then the Second Chief of the General Staff, makes assertive statements such as “the Turkish General Staff is close to Israel” and “he does not know a Turkish officer who would not support Israel under all circumstances”. In sum, the TSK assumed a protective role in Turkish-Israeli relations.

The military cooperation with Türkiye, known in Israel by the code name “Merkava“, is unique as the only military agreement between Israel and another country. According to this agreement, regular meetings are held every six months between the heads of the Military Intelligence Departments and sometimes the chiefs of the General Staff in both countries. In fact, the then Israeli Chief of Staff, Yitzhak Rabin, described the relations as a “special relationship”. The scope of this relationship includes the exchange of views and information, cooperation on various military issues, exchange of expertise in the military industry, and many other issues that are probably still kept secret. The common threats that the two states share intelligence on are the Soviet Union, some Arab countries (especially Syria), and terrorism. Although Türkiye’s anti-Soviet intelligence largely comes from the United States, Ankara has access to information that will benefit Israel on some issues. In this sense, according to one official, Ankara has become “Israel’s eyes” in the Arab world. However, this situation is reciprocal, because Israel’s intelligence network in the Arab world at that time was much more advanced than Türkiye’s.

Although Ofra Bengio could not find any concrete documents regarding the military coordination between the two countries, according to a high-ranking Israeli official, in 1959, the two armies prepared a strategic plan for a joint intervention in Syria or another Arab country. This was the first joint military plan in the history of the two countries. At that time, Israeli Chief of Staff Haim Laskov made a secret visit to Türkiye and met with all the high-ranking military officials, especially Chief of Staff Rüştü Erdelhun. With the contributions of Yitzhak Rabin, a joint naval force plan was even created between the two countries, which was confirmed by the Head of the Turkish Military Intelligence Department.

Although relations cooled somewhat after the 1960 coup, there were some concrete developments in military coordination. For example, in August 1966, an Iraqi Mig-21 that took off towards Israel was allowed to land at one of the joint Turkish-American bases for refuelling. In September 1970, Israel informed Türkiye of the process of massing troops on the Syrian border. In addition to these, developments such as the joint production of air cannons for Germany, Israel’s sale of parachutes to the Turkish Air Force, the training it provided to TSK elements in various fields, and the permission to use Turkish airspace to provide military supplies to Iran and the Iraqi Kurds are also important in terms of military coordination. Several high-level commanders within the TSK are aware of Israel’s support for the Kurds, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is not informed about this. In addition, the relationship between the air forces of the two countries is also strong. In addition, Türkiye wants to benefit from Israel’s atomic work, but this time Israel is not willing. In short, military cooperation was at a very high level during the golden age of relations. Visits also became more frequent. For example, in 1964, Chief of General Staff General Cemal Tural visited Israel. In the same year, an open visit was made to Türkiye by the Israeli Military Academy under the command of Uzi Narkis. Again in the same year, Israeli Air Force Commander Ezer Weizman planned to visit Türkiye, but the visit was later abandoned when the Cyprus Problem arose.

The Cyprus Problem, which began with the virtual collapse of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960 in 1963, affected every area of Turkish Foreign Policy, as well as Turkish-Israeli relations. As a result of Makarios’ policies, the Greek Cypriots managed to become the sole representatives of the island with Resolution 186 issued by the United Nations in 1964. In this case, while Türkiye was preparing for military intervention, the crisis was calmed with the intervention of U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, and Johnson warned Prime Minister İnönü not to intervene in Cyprus in a letter. The “Johnson Letter”, written in a style that lacked tact, harmed Turkish-American relations, especially when it was reflected in the public opinion. Ankara, which had to postpone military intervention until 1974 during this period, still bombed Greek Cypriot positions on August 8-9 to protect the Turkish Cypriots.

The Cyprus Problem encouraged Prime Minister İnönü and the Turkish State to diversify Turkish foreign policy. İnönü and all subsequent decision-makers wanted to increase their options in foreign policy instead of fully trusting the U.S. For this reason, Türkiye began to open up to Arab countries and the Islamic world in general to gain support in UN votes, which caused concern in Israel. In addition, Ankara began to develop its relations with Moscow. Türkiye’s opening up to the Arab world caused Arab countries to act together and try to convince Ankara to cut off its relations with Israel. During that period, warning letters were even written to journalists who wrote pro-Israeli articles, and some were tried to be won over by promising economic benefits. In fact, in 1965, 13 Arab states offered to vote in favour of Türkiye in the UN in exchange for completely cutting off its relations with Israel. Türkiye, on the other hand, did not want to go that far and, considering the example of Egypt, which provided military support to Makarios, did not fully trust the Arab states. Nevertheless, the four new principles determined by the Turkish State in 1965, which did not please Israel, were as follows:

- To exert maximum effort to ensure rapprochement with the Arabs,

- To keep relations with Israel at the lowest level,

- Not to bow to the Arabs beyond this,

- Not to allow relations with Israel to get in the way of rapprochement with the Arabs.

The Cyprus Problem generally has a negative impact on Turkish-Israeli relations. After Türkiye’s limited interventions, even expressing regret to Makarios on humanitarian grounds provoked reactions in Ankara. Türkiye expects support from Israel on this issue; since Greece does not recognize Israel, and Türkiye is the first and only country with a large Muslim population to recognize Israel (except for Albania, which was a communist state at the time). However, the Republic of Cyprus is a state that recognizes Israel, and Israel has a moral debt to the Cypriots who assisted the migration of Jews to Palestine while Cyprus was a British colony. For this reason, Israel’s stance on the Cyprus Problem negatively affects Israel’s image in the Turkish public opinion. At this point, two camps emerge on the Turkish side. While a broad front such as the Turkish Armed Forces, the Kemalist-Atatürkist intelligentsia, and the Ministries of Reconstruction, Agriculture, Rural Affairs, Labor and Tourism, which develop joint projects with Israel, advocate openly developing relations, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs argues that more caution should be taken on this issue, considering the support of Arab and Islamic countries in UN votes. However, from 1965 onwards, under the influence of Prime Minister İnönü and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Türkiye’s support gradually began to shift towards Arab countries. Ankara concerned that Makarios’ third-world foreign policy would increase the number of friends of Greek Cypriots in the world, therefore abandoned its classical Westernist policy and began to use Muslim identity and anti-imperialist discourses more intensively in Turkish foreign policy to build a more multi-dimensional foreign policy.

On the Israeli side, which realized that relations were deteriorating during this period, Eliyahu Sasson continued to advocate an alliance with Türkiye. Sasson advocated continued support for Ankara, which did not sever its relations with Israel despite Arab pressure. During these years, with Türkiye’s efforts, some visits and news were censored on Israel’s Arabic radio, and it was believed that the Arab people and the public did not know that Türkiye and Israel were continuing their cooperation. Over time, this demand also encompassed all other press and publication organs, and it became increasingly impossible to report/talk about Türkiye-Israel relations. Over time, the erosion of relations accelerated and after 1966, crises began to occur in Turkish-Israeli relations. Indeed, at the end of 1966, Ankara informed the Israeli military attaché of its decision to end intelligence relations. Following this, the signing of a declaration by some American rabbis emphasizing concerns about the security of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Greek Orthodox Church in Istanbul accelerated the negative course of relations even further. In fact, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs tried to prevent this attempt in order not to damage relations with Türkiye, but it was unsuccessful. In this environment, the Foreign Ministers of the two countries, İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil and Abbe Eban, held a secret meeting in Brussels. During this meeting, Çağlayangil, who demanded that military and intelligence cooperation be stopped, also demanded that Israel abide by the principle of secrecy in its relations with Türkiye, as it did in its relations with Iran. Thereupon, Tel Aviv tried to infiltrate Türkiye through the Jewish lobby in the U.S., but this was not very effective. Despite all these efforts, after 1966, Turkish-Israeli relations entered a period of freezing that would last for about twenty years. However, even during this period, relations would not be completely severed and contact between the secret services would continue. In addition, Türkiye allowed the Israeli Air Force to use its airspace for flights to and from Iran. Israel also extended a hand of friendship to Türkiye by assisting after the 1967 Adapazarı earthquake.

To summarize the process of the breakdown of the alliance between the two countries; Türkiye’s policy of seeking support in Arab and Islamic countries to find support for Ankara’s position in the Cyprus Problem, and its re-appropriation of its Muslim identity and its beginning to support the Palestinian cause, negatively affected relations with Israel. In this sense, the cautious attitude of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs gradually spread to the Turkish Armed Forces and other security units, and over time, close relations with the Arabs began to overshadow close relations with Israel. During this period, the rising anti-imperialist left movements in Türkiye would also keep a very close distance from Israel, and some leftist student leaders would even go to Palestine to receive military training. In addition, the assassination of Israeli Consul General Efraim Elrom in the early 1970s also had a negative impact on relations. Israel’s failure to support Türkiye in UN votes accelerated this process and created disappointment in Ankara. For this reason, Turkish-Israeli relations, which deteriorated in the late 1960s, would only be fully restored in the 1990s.

Part Three: Rapprochement in the 1990s: Causes and Players

The Turkish-Israeli rapprochement in the 1990s has a more common project appearance compared to the Peripheral Alliance, which was put into practice with Israeli efforts in the late 1950s. In this period, both sides exerted equal effort and desire. An important difference is that while the Peripheral Pact was made more against the threats of communism and Pan-Arabism, this time the threats of radical Islam and terrorism are at the forefront. In addition, Iran, which was a partner for the two countries in the late 1950s and 1960s, has now become one of the main sources of threat – after the Islamic Revolution in 1979. In addition, as a result of the Israeli-Egyptian rapprochement in the late 1970s and Egypt’s recognition of Israel, Türkiye, which was much more alone and isolated in this regard in the 1960s, is now able to act more boldly on its own. In addition, Jordan, the secret ally of Israel that recognized Israel after 1994, would also join the partnership of the two countries in the 1990s. In addition, unlike the Peripheral Pact, this time the relations were extremely open and public.

George Gruen, who analyzed Türkiye’s policy towards Israel in the 1948-1960 period, emphasized that the most important component of Ankara’s attitude was “ambiguity“. Indeed, both because it was the only country with a large Muslim population that recognized Israel and because it had a natural leadership in the Islamic world due to its Ottoman heritage, Ankara could not display such a clear and strong desire in its relations with Israel as Tel Aviv. However, the foundations of the friendship between the two communities were laid during the Ottoman Empire. So much so that in 1492, the Ottoman Empire opened its doors to Jews fleeing persecution in European countries, and the Jewish community in return contributed to the enrichment of the Ottoman Empire. In the late Ottoman period, during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, the Ottomans continued their warm attitude towards the Jews. However, Abdulhamid could not agree with Theodore Herzl on the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine and rejected his offer (land in Palestine in return for the payment of Ottoman debts). However, even during the reign of Abdulhamid, who was concerned about not losing the support of the Arab population and keeping the Empire on its feet, Jews were allowed to go to Palestine for religious reasons, that is, to establish the Yishuv (Jews who settled in Palestine before the establishment of Israel). This situation is also reflected in a book by the famous writer Falih Rıfkı Atay, which includes his observations on Palestine: “The new towns and villages of Palestine are Jewish creations. This is a brand new Palestine. The Arab day labourer presses the grapes and the fat Jew drinks the wine.”

This uncertainty, which continued during the period of the Republic of Türkiye, affected relations with both the Jews of Türkiye and the Yishuv in Palestine. The Jews of Türkiye, who acted as a key bridge in Turkish-Israeli relations, lived in an environment with a high level of tolerance, although they were occasionally subjected to anti-Semitic attacks. There are two reasons for the attacks on Jews: (1) Conspiracy theories that Jews dismantled the Ottoman Empire to establish a state in Palestine, and (2) the better economic situation of the Jews. Indeed, the effect of the second reason can be seen in the Thrace Incidents of 1934. However, in general, Jews were approached positively in the Republican period, just like the Ottoman period. The great leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who was also unfairly accused of being a “Jewish convert” (Sabbatean), said that Jews could live in peace in Türkiye because they had proven their loyalty to the Turkish nation. Jews loved Atatürk and called him “El Gadol” (The Great). This situation was crowned by the fact that Abravaya Marmaralı became the first Jewish deputy to enter the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1935 during Atatürk’s period. More importantly, Türkiye welcomed around 200 Jewish academics and doctors who had escaped from Nazi Germany during this period. According to the author, Türkiye’s close relations with the Jewish Agency during the Atatürk era are examples of Atatürk’s pro-Jewish attitude. Another example is Ankara’s participation in the 1936 Tel Aviv Levant Fair, financed by the Zionists. Indeed, members of the Yishuv also participated in the International Izmir Fair in 1938.

(Samoel) Abravaya Marmaralı

Türkiye’s attitude towards the establishment of Israel is also one that maintains a line of uncertainty. Although Ankara opposed the 1947 Palestine Partition Plan, it recognized the State of Israel, which was established in 1949, and became the first – and for a time, the only – Muslim country to do so. In this sense, unlike other Arab states, Ankara does not consider Israel to be inherently sinful and does not reject its existence. Therefore, the most influential term in Ankara’s Israel policy after its approach to uncertainty should be “balance”. Türkiye remained militarily neutral during the 1948-1949 Israeli War of Independence (1948 Arab-Israeli War in Turkish literature), the 1956 Suez Crisis, the June 1967 War (Six-Day War), and the October 1973 War (Yom Kippur War). During this period, Ankara did not send its armies and did not support either side.

The attitudes of political parties in Türkiye towards Israel during this period are not very promising either. First of all, throughout the Cold War, there has been a clear anti-Israel sentiment on both the far left and the far right in Türkiye. Communist-socialist groups on the far left and Islamists on the far right have been on a line that views Israel’s existence with suspicion and supports the Palestine Liberation Organization. Some elements on the far left have even gone to Lebanon and Jordan to receive guerrilla training and fought in the ranks of the PLO. Islamists have always been skilled at turning Israelis and Turkish Jews into “usual suspects” with their conspiracy theories and patriotic rhetoric. The National Vision (Outlook) movement (Milli Görüş), led by Necmettin Erbakan in particular, has represented a clear anti-Zionist line in this sense. While Erbakan claimed that Israel was a national security problem for Türkiye, he also considered the European Common Market to be a Zionist plot. With such conspiracy theory-based ideas, Islamists have managed to mobilize the conservative segment in terms of anti-Israel sentiment. The nationalist right’s attitude towards Israel has been more ambiguous. Indeed, while the extreme nationalist-Turkists who showed interest in Adolf Hitler and the Nazi ideology in the 1930s and 1940s (such as Nihal Atsız) did not approach the Jews in a friendly manner, in later periods they began to like the Zionists’ struggle for a nation and to support the Jews due to Israel’s positive relations with the U.S. and the fact that it was not a communist state. The view that the Arabs had betrayed the Ottomans was also quite influential in the extreme nationalists, and Alparslan Türkeş would differ greatly in this regard from Nihal Atsız, whom he admired in his youth. Atsız, on the other hand, was anti-Semitic. For example, he said, “The Turkish nation has three enemies inside: communists, Jews, and sycophants.” However, over time, even Atsız appreciated the efforts made by Israel in its establishment and development process. While Alparslan Türkeş praised Israel’s military victories, he also praised Israel’s advancements in science, technology, and economy. Türkeş accepted Israel as a reality of the region and argued that Arabs should make peace with Israel.

When we look at the Turkish people, while there may be admiration and support for Israel in intellectual circles, support for Palestine has been higher among the public. Especially after the Intifada, the courage of the Palestinians began to be appreciated. Again, when there were deaths among the people as a result of Israel’s harsh policies and practices, a significant increase in Palestinian sensitivity was observed.

Despite these differences, some factors bring the two countries together. First of all, both countries are trying to be democracies, unlike totalitarian or dictatorial regimes. Both countries are facing the West. Since neither country is Arab, there is a kind of consensus between them. In this sense, there is also a contemptuous attitude towards Arabs in both societies and according to Bengio, this situation is surprisingly more intense in the Turks. The economies of the two countries are complementary to each other. In addition, the armies of both countries are considered to be among the strongest in the Middle East. Under the influence of these factors, Ankara decided to raise the Ankara representations of both Palestine and Israel to the level of embassies on December 19, 1991. According to Efraim Inbar, the Israeli side, unaware of the long discussions that took place in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs before this decision, was left in a state of great surprise by this decision. So what were the factors that pushed Türkiye to this decision?

First, Türkiye has overcome the psychological barriers described earlier and has reached a more relaxed and easy position in its relations with Israel. The reason for this is that an Arab state such as Egypt has also normalized its relations with Israel and the Arab states have lost their ability to act together in the 1970s by the 1990s. During this period, the oil weapon was no longer as effective as it was during the 1973 OPEC Crisis. In addition, it can be considered that the fact that the Soviet Union and Greece established full diplomatic relations with Israel in the same year before Türkiye had an impact on Ankara. The most effective factor in Ankara’s eyes is the initiation of the peace process between Israel and the Arab states at the Madrid Conference held in October 1991. The presence of the Palestinian delegation at this conference and sitting side by side with the Israelis was welcomed by Türkiye. Because, from Türkiye’s perspective, the greatest source of concern in relations with Israel has always been the Arab states’ reaction to Ankara due to the Palestinian Question. As if to confirm this development, immediately after the Oslo Accords were signed between Israel and the PLO in September 1993, the then-Turkish Foreign Minister Hikmet Çetin paid an official visit to Israel. Then, in July 1994, he attended the ceremony held for the then Prime Minister Tansu Çiller, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, who won the Nobel Peace Prize and met with all three leaders. Again in 1994, before the ink had dried on the Israel-Jordan peace treaty, Tansu Çiller paid an official visit to Israel (November 3, 1994). Çiller, however, also visited the Palestinian Authority and Egypt to balance this visit. Interestingly, the start of peace talks between Israel and Syria increased Türkiye’s desire and courage to develop its relations with Israel. In December 1995 and January 1996, the most productive peace talks between Israel and Syria were held in Maryland-Wye. Although these agreements could not conclude, Türkiye feared that these attempts by Israel would have a negative outcome for itself, and the following month, President Süleyman Demirel went to Israel – the first Turkish President to visit Israel. During this period, Türkiye”s concerns about Syria-Israel normalization became apparent when the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time, Onur Öymen, said, “We kindly request that you put an end to official talks with Syria.” In this sense, while Türkiye welcomed Israel’s normalization with Jordan and the PLO, it was wary of normalization with Syria, but all of these attempts resulted in Ankara taking the initiative to normalize and develop its relations with Tel Aviv.

The driving force behind the rapprochement between Türkiye and Israel in the 1990s was undoubtedly the TSK. The 1996 agreement, like the Environmental Pact, was based on a strategic partnership. While General Çevik Bir, who was the Deputy Chief of General Staff at the time, stood out as an active figure in this process, the basic thoughts of the Turkish Army were; The alliance with Israel can be stated as (1) the continuation of good relations with the U.S. and thus the prevention of developments against Ankara regarding the Kurdish Question, and (2) the barrier against the increasing political Islamist movements within the country by making an open alliance with Israel. Indeed, some academics compared Israel and Türkiye to each other during this period and classified them as “military democracies”. The Turkish Army became an effective institution in foreign policy in the 1990s against PKK terror and the rising political Islamist threat. According to the author, the short-term duties of the Foreign Ministers during this period can also be considered as an indication that the TSK was more effective. Indeed, eleven Ministers served in this period in ten years. In the 1980s, this number was only three. During this period, TSK commanders held briefings and openly expressed their views on foreign policy in front of the public or to opinion leaders. This position of the army is undoubtedly closely related to the fact that the army was at the core of Turkish modernization and that the great leader Atatürk was a leader with a military background. In these years, the TSK had to develop new policies in three regions in general after the Cold War: the Caucasus and Central Asia, the Balkans, and the Middle East. These regions were seen as target regions, especially by the civilian leaders of the period (such as Turgut Özal), in terms of increasing Türkiye’s economic and political power. In this way, Ankara had the opportunity to prove that it was still important after the end of the Cold War and the removal of the Moscow threat. In this sense, although Çevik Bir claimed that Türkiye was one of the few countries whose importance increased after the Cold War, the understanding of drawing a “Western curtain” against the East, including Türkiye, instead of the “iron curtain” against the USSR in Europe, became stronger.

During this period, some weaknesses that convinced the TSK to redefine and strengthen its relations with the West also emerged. The first of these was the technological inadequacies noticed during the Gulf War. The Turkish Army’s power was far behind the U.S. in terms of electronic warfare equipment, air refuelling and night air combat. Secondly, the emergence of long-range ballistic missiles in terms of threats originating from the Middle East helped Türkiye understand that it needed to be prepared for such a situation. Thirdly, the reluctance of European countries to provide equipment to Türkiye and even the embargo imposed by some of them directed Ankara to alternative manufacturers. In all these matters, Israel would become a good option and thus the idea of military modernization would play a driving role in the Turkish-Israeli rapprochement in the 1990s.

It is noteworthy that in this period, the centre and even some extreme parties in Türkiye’s domestic public opinion adopted a stance closer to Israel. The centre-left parties abandoned their old left habits, adopted closer relations with Israel and began to act more neutrally on the Palestinian-Israeli issue. Even the Turkish nationalist MHP (Nationalist Action Party), which is considered far-right, openly advocated developing relations with Israel under Türkeş’s leadership. In contrast, Erbakan’s RP (Welfare Party), another far-right actor rising on the political scene, differed considerably from other parties with its anti-Zionist and anti-Israeli views and began to receive more intense support. The fact that the PKK terrorist organization led by Abdullah Öcalan, who was very influential in Türkiye during these years, received support from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Libya, the Soviet Union, and the PLO also led the security bureaucracy and political parties in Türkiye, except for the RP, to stand close to Israel during this period. While reactions were directed particularly at Syria on this issue, Türrkiye also found itself in a state of mind surrounded by enemies in the region, like Israel, years later. In this respect, for the first time in years, the focus shifted from the external threat of the Soviet Union to the internal threat of the PKK in the 1992 National Security Council (MGK) document.

Another important issue is undoubtedly the stopping of Islamists within the country. The army is disturbed by the increasing support of the RP and the threat of Islamism. While the centre-left and centre-right parties were losing power throughout the 1990s, Kurdish politics and especially Islamist politics were rapidly gaining power. The RP, which won Ankara with Melih Gökçek in the 1994 local elections and Istanbul with Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, also won the general elections held in December 1995, and for the first time in the country’s history, an Islamist party became the number one party in the country. The army’s attitude towards the RP at that time was so negative that General Fevzi Türkeri even said, “If necessary, we will engage in armed struggle.” The RP has come face to face with the TSK numerous times in the 11 months it has been in power with the Welfare Party coalition government (between the Welfare Party and the True Path Party-DYP). While Erbakan and the elected government want to develop relations with the Islamic world, state institutions consisting of appointees such as the TSK and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs advocate rapprochement with the West. The main reason for the incompatibility between the state and the RP is its relations with Israel. Far from being allies with Israel, Erbakan and his team prefer to establish hostile relations if they have the opportunity. In the eyes of the RP, Israel is an arm of the artificially created American and Western imperialism in the Middle East and its aim is to hinder Muslims and Turks. There are three different dimensions to the army’s approach to Israel: (1) military/professional, (2) regional/strategic and (3) political/ideological concerns.

First of all, the TSK wants technological support from Israel regarding the ambitious modernization program and other developments in the Turkish Air Force that it started in the 1980s. This is closely related to the reluctance of the U.S. and European countries to transfer technology. Secondly, the TSK believes that Türkiye’s regional power can be increased by getting closer to Israel and that it can better combat threats, especially those originating from Syria, Iraq and Iran. Moreover, thanks to the Jewish/Israeli lobby, relations with Israel can simultaneously develop relations with Washington. Thirdly and finally, the TSK believes that strengthening relations with Israel, which is more suitable for a Western-style secular democracy compared to Islamic countries, in terms of protecting the Kemalist-secular regime, can be a good antidote against the threat of radical Islam within the country. For these reasons, a kind of “strategic triangle” is formed between Türkiye-U.S.-Israel during this period.

Despite these favourable conditions, incompatible situations have continued in Türkiye-Israel relations. The first and most important of these is that rapprochement with Israel has created controversy in Türkiye. First of all, the voters of the RP, the largest party in the country (with a vote rate of 21.4 per cent at the time), were completely against this. Other parties, fearing the RP, had difficulty taking a clear position on this issue. In Israel, all political parties supported an alliance with Türkiye. Secondly, since some countries in the region questioned Israel’s existence, it was more difficult to enter into regional alliances with Israel. Indeed, while Türkiye was easily included in agreements such as the 1937 Sadabad Pact, the 1952 NATO, the 1955 Baghdad Pact and the 1959 CENTO, Israel was not included in such agreements. Thirdly, Türkiye did not enter into a major war after the War of Independence in 1922. However, Israel entered into many wars after its own War of Independence in 1948-1949. However, in this regard, it is possible to speak of harmony rather than incompatibility in the context of the need for a strong army in both countries. Fourth, although the army was influential in both countries, in Türkiye, the army (TSK) also played a political role, while in Israel the army only dealt with professional issues and never intervened in politics.

During this period, the ideas of Efraim Inbar, the director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Peace at Bar-Ilan University, are noteworthy as a person who advocated the Turkish-Israeli alliance. According to Inbar, establishing relations with Türkiye will not disrupt Israel’s relations with Arab countries, but on the contrary, will strengthen the peace process with these countries. Furthermore, being an ally of Türkiye will create the opportunity for Tel Aviv to surround threats such as Iraq, Syria and Iran. Barry Rubin, an academician and member of the BESA Center, is another important advocate of the Turkish-Israeli alliance. Apart from such open advocates of the alliance, some argued that relations should be conducted more covertly, such as Alon Liel, Israel’s chargé d’affaires to Türkiye at the time. So much so that Liel said, “We may love each other, but we don’t have to hug and kiss in front of everyone.”

There were also those in Israel who opposed the alliance with Türkiye. For example, Stuart Cohen from Bar-Ilan University thinks that an alliance with Türkiye could negatively affect the peace process with Syria, which is more important for Israel, and states that Israel’s alliance with Ankara would tie its hands and feet to the Kurdish Question. In a similar vein, Gerald M. Steinberg also points out that an alliance with Ankara could put pressure on Israel on issues such as the Cyprus Problem, the Kurdish Problem, and relations with Greece. Chemi Shalev from the Ma’ariv newspaper also warns that the love between Israel and Türkiye may not last long, recalling that even the Environmental Pact from Ben-Gurion’s time was temporary. Israeli researcher Leon Hadar, who lives in the US, also feels the need to warn his country about cooperating with undemocratic governments.

Ultimately, despite concerns, a concrete alliance was built between the two countries in the 1990s. However, since there are concerns that this alliance will remain in the military-security field, Alon Liel makes the following statement: “The management of Turkish-Israeli relations should be transferred from generals to diplomats.” The most important factors motivating Israel in this regard are; that the Muslim world and Central Asia will be more penetrated thanks to Türkiye. Indeed, an alliance with Ankara will open doors for Israel in relations with many countries such as Pakistan, Indonesia, and the Turkic Republics.

The Turkish-Israeli agreement was officially signed in 1996. Two ministries actively took part in the negotiations: the Ministry of Defense and the Prime Ministry. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on the other hand, remained in the background, as in the Peripheral Alliance. One of the architects of this alliance was David Ivri, the General Manager of Foreign Minister Yitzhak Rabin. The efforts of Ivri and Rabin, which began in the 1980s, laid the foundations of the Turkish-Israeli alliance in the 1990s. The key actor on the Turkish side was General Çevik Bir. Interestingly, Benjamin Netanyahu, who has been shown as one of the reasons for the tense relations with Türkiye in recent years, was also a politician who advocated close relations with Türkiye at the time. Yitzhak Mordechai, who was the Defense Minister of the Netanyahu government, was also the person who strengthened the Türkiye-U.S.-Israel triangle and initiated the joint naval operations, the first of which began in January 1998. Interestingly, the alliance in Türkiye-Israel relations took shape in 1996 during the term of Netanyahu, Israel’s most pro-Türkiye leader, and Erbakan, Türkiye’s most pro-Arab leader.

The U.S. was a silent but influential actor in this process. Nicholas Burns, the spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the time, emphasized the U.S.’s support for the Türkiye-Israel alliance and reminded that they were allies with both countries. Although Burns did not give a specific date, he also stated that his country was working on this issue. This situation began with talks between Israel and Türkiye in the 1980s regarding the development of Phantom aircraft but was interrupted due to the beginning of the First Intifada (1987). Israeli sources state that U.S. President Bill Clinton also made great efforts in this regard. The U.S.-based B’nai B’rith, known as the Jewish lobby, the American Jewish Congress, the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations and the Jewish National Security Institute (JINSA) always supported this alliance. During this period, there were individuals within the Jewish lobby who made propaganda in Washington in favour of Türkiye against the Armenian and Greek lobbies. However, U.S. support for Turkish-Israeli rapprochement would also be limited, as Washington was also concerned that the friendship between Israel and Türkiye would overshadow relations with Washington. Similarly, Washington did not want Israeli military companies to overtake American military companies and become Türkiye’s main supplier of materials. For example, the U.S. Ambassador at the time, Mark Grossman, openly opposed the agreement for Israel to renew F-4 fighter jets. Similarly, the U.S. company General Dynamics undermines Israel’s offer to renew Turkish tanks by leasing Abrams tanks to Türkiye. The U.S. is also concerned about the transfer of its sophisticated technology to Türkiye through Israel.

Part Four: Building Blocks of Rapprochement

Several different expressions are used for the rapprochement process between Türkiye and Israel in the 1990s, such as alliance, rapprochement, concord, entente, compromise, cooperation and strategic partnership. Another state that was included in the rapprochement between Türkiye and Israel during this period was Jordan. Jordan, which recognized Israel during this period, was a junior partner in this alliance. Thanks to this alliance, Türkiye established an alliance with a Middle Eastern country that was not its border neighbour for the first time. In addition, this was Türkiye’s first comprehensive cooperation with a country that was not a member of NATO. Establishing close relations with a Middle Eastern country puts Ankara in a similar position to NATO members such as the U.S., France, and the United Kingdom (UK). Attempts to value and portray the alliance as important were so effective at the time that Zvi Elpeleg, the Turkish Ambassador at the time, even said that an Israel without Türkiye would “be blown away like a leaf in the wind”.

The Turkish-Israeli alliance of the 1990s, which led to the 1996 agreement, did not come into being overnight. It was experienced through the concrete conjuncture of initiatives that began in the 1980s. The alliance is also quite comprehensive; it has political, diplomatic, military, economic and intelligence dimensions. The positive fruits of this alliance also began to be reaped immediately. For example, the Minister of Interior at the time, Nahit Menteşe, stated in 1992 that Türkiye and Israel were cooperating against drugs, terrorism, and organized crime and that they had made great strides in the fight against crime. In addition, the night vision equipment and anti-rocket systems used in helicopters sold by Israel to Türkiye increased the success of the TSK’s PKK operations. It is stated that Israel also assisted Türkiye in the capture of PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan and the capture of the Kurdish terrorist cell house of the Turkish Hezbollah organization. Military relations also developed rapidly from 1992 onwards. Mutual visits became more frequent and eventually, in 1996, the level was reached where the Israeli Air Force would be trained in Türkiye and the Turkish Air Force in Israel. In addition to Çevik Bir, the Chief of General Staff at the time, İsmail Hakkı Karadayı, Air Force Commander Halis Burhan and Naval Force Commander Güven Erkaya also became the initiators of the military alliance. Thus, the famous agreement was signed on February 23, 1996. The agreement, which determined its goal as providing military training cooperation between the two countries, included the following articles:

- To ensure cooperation at various levels based on the exchange of personnel and information,

- To conduct mutual visits between military academies, units and headquarters,

- To conduct training and exercise practices,

- To send observers to monitor military exercises in both countries,

- To exchange officials who will carry out the task of collecting and sharing information, especially in social and cultural areas including military history, museums and archives,

- To conduct mutual visits of warships.

Among the issues highlighted in the five-page document is the article on “confidentiality of security information.” In this sense, all exchanged information and expertise are subject to the provisions of the secret security agreement dated March 31, 1994. The content of the 1994 agreement is never made public, but it is clear that it imposes an obligation on the parties to maintain the confidentiality of the exchanges. According to Ofra Bengio’s analysis, the Turkish side has used this agreement as a psychological element against threats such as the PKK and RP by leaking information over time. Indeed, the struggle between the RP and the TSK intensified after the agreement. Publications were made in the Milli Gazete in particular, suggesting that ties with Israel should be cut to save Türkiye from terrorism. Some RP party officials also announced that they would cancel this agreement. However, the Erbakan government, under pressure from the TSK, was not only unable to cancel this agreement but was also forced to sign an agreement in August 1996 for the modernization of Türkiye’s Phantom aircraft by Israel. During this period, Chief of General Staff İsmail Hakkı Karadayı told Prime Minister Erbakan that he should not be too emotional and that he should sign the agreement. Türkiye was gradually moving towards the February 28, 1997 process.

The intensity and scope of the new relations can also be understood by the fact that Türkiye increased the number of military attachés in Israel from one to three (officials from air, sea and land forces) in July 1998. While Türkiye normally assigns one military attaché to countries other than the U.S., Germany, and France, Israel became the fourth country to assign three attachés in this sense. This is an important symbol for explaining the importance given to relations and the depth of relations. Israel also assigns two military attachés to Türkiye during this period. In addition, military visits increase significantly. Matan Vilna’i, Amnon Lipkin Shakak and İsmail Hakkı Karadayı are the high-level commanders who carried out the military visits during this period.

The protocol signed on September 18, 1995, which allows pilots from both countries to train in each other’s airspace, is a very important development, especially for the Israeli Air Force. Thanks to this, the Israeli side will be able to conduct exercises in a large area for the first time, will be relieved of claustrophobia and will be able to access new information about countries such as Iran, Iraq, and Syria. According to the agreement, training flights will be held eight times a year. Thus, by the end of 1999, almost all Israeli pilots will have gained serious experience in Türkiye. Turkish pilots will also gain new experience at the Shdema Air Base in the Negev Desert and develop techniques for attacking long-range anti-aircraft missiles as well as radar evasion and electronic signal jamming. In addition, in June 2001, the American, Turkish and Israeli air forces will conduct a joint air exercise over Konya. Israeli F-15 aircraft will even take part in the 90th anniversary celebrations of the Turkish Air Force.

The naval forces of the two countries also cooperate closely during this process. According to the agreement, warships are allowed to enter each other’s ports. It is also likely that Israeli submarine crews are allowed to be trained in Türkiye. In addition, with the contribution of Defense Minister Yitzhak Mordechai, joint naval exercises are held in the Mediterranean between Türkiye, and Israel, and the U.S. Invitations made to Egypt and Greece during this process are withdrawn. In January 1998, Turkish and Israeli warships conducted a joint exercise. In April 2001, Israel and Türkiye conducted joint exercises at the Marmaris Aksaz Naval Base, which are reported to have military rather than humanitarian purposes and in which the US does not participate.

By 1999, a dialogue is also initiated between the land forces of the two countries. However, progress in this area has been more limited.

Arms agreements between the two countries also increase during this process. Ankara, which does not accept the human rights criteria set by European countries and the US, turns to Israel during this process. In this way, an agreement was reached for Israel to modernize 52 F-4 fighter jets and 46 F-5s belonging to Türkiye. These agreements, signed in 1996 and 1998 and totalling 700 million dollars, were the largest agreements the Israeli aircraft industry had ever made with another country. In addition, Ankara and Tel Aviv signed a 110 million dollar agreement in February 2002 for Israel to install electronic warfare systems on Turkish helicopters. In fact, during this period, Türkiye, Israel, and the U.S. began to develop a three-way ballistic cooperation mechanism together.

Intelligence sharing between the two countries also reached its peak during this process. In fact, there was a tradition between the intelligence services of the two countries that dates back to the Peripheral Pact. However, this situation became more comprehensive in the 1990s. For example, Israel provided critical information to Türkiye regarding the Mig 29 fighter jets in the Syrian Air Force. Israeli special forces even take part in Türkiye’s raids on Kurdish regions in Northern Iraq. Although this news has not been confirmed, the fact that it has even become a topic of discussion shows how extensive the cooperation between the two countries has become.

On March 29, 2002, Türkiye signed a secret agreement with Israel Defense Industries for the modernization of 170 Turkish M-60A1 tanks for $668 million. During this period, Chief of General Staff General Hüseyin Kıvrıkoğlu allayed Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit’s doubts and defended this purchase.

The rapprochement process is also reflected in the relations between the peoples. In this process, the willing party has been Israel. Past experiences have taught Israel that if it cannot provide social support in this regard, relations can easily be severed. Therefore, action is taken to include the people in this process for the sake of continuity of relations. In this context, priority is given to political and diplomatic visits. For example, Prime Minister Ehud Barak visited Türkiye three times during his short 18-month term in office. Barak’s more peaceful behaviour on the Palestinian Question compared to Netanyahu also plays a role in Ankara’s positive attitude towards these visits. During this period, economic relations between the two countries also developed, and the then Foreign Minister İsmail Cem responded to those who criticised this issue by reminding them that many member states of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation have intense economic relations with Israel. Even Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan consults the Governor of the Bank of Israel, Jacob Frenkel, on inflation during his time in power. Relations are also developed in telecommunications, a sector in which Israel is good. For example, Israel participated in the Bilisim 2001 CEBIT Fair in Istanbul at the end of 2001 to establish relations with Turkish companies and expand its information technology network. Indeed, as a result of these initiatives, the trade volume between the two countries increased to 1.2 billion dollars by the end of 2002. Relations also developed rapidly in the field of tourism. In 1995, the number of Israeli tourists visiting Türkiye reached 287,000. Gambling tourism, which was not yet banned in Türkiye, was particularly effective during this period. Thanks to tourism, social relations also improved. Israel’s helping hand to Türkiye during the 1997 Kırıkkale fire and the 1999 earthquake also improved its image in Türkiye and strengthened bilateral relations. Especially after the earthquake, Israel built a village for the homeless in Adapazarı and spent 6 million dollars for this purpose. Prime Minister Ecevit praised Israel’s actions with the words, “You are teaching an extraordinary lesson in humanity. The Turkish people will never forget what you have done.” During this period, talented Israeli football player Haim Revivo, who played for Fenerbahçe football team, became a symbol of bilateral relations and Turkish-Israeli friendship.

Haim Revivo

In the 1990s and 2000s, cooperation in the fields of culture-art and science-education also gained momentum. In 1999, the YÖK provided an annual donation of $500,000 to the Süleyman Demirel program established at the Tel Aviv University Moshe Dayan Center, while Tel Aviv University provided equal support. In addition, during this period, the work of famous Turkish author Orhan Pamuk, The Black Book (Kara Kitap), was translated into Hebrew, and the books of Israeli author Amos Oz were translated into Turkish.

Despite the rapidly developing relations between the two countries, the problems have not completely disappeared. The most important of these problems is the Kurdish Question. Although Israel supports Türkiye in its fight against the PKK, problems continue in this regard due to the presence of the Jewish Kurdish community in Israel, which is sympathetic to the Kurdish political struggle, and the close historical relations between Israel and the Kurds of Northern Iraq. In addition, the statements of some Israeli ministers accepting the 1915 Events as the Armenian Genocide also damage bilateral relations. Another issue is the corruption incidents that occur from time to time in military tenders. The last important issue is the efforts of Arab states to damage the rapprochement between Türkiye and Israel.

Part Five: Effects and Reactions

The rapprochement between Türkiye and Israel in the 1990s, unlike the Peripheral Alliance, was experienced openly and therefore caused harsh reactions. While only Jordan welcomed this process among the Arab states, other Arab states adopted a reactionary stance. Some Arab intellectuals even considered this as Türkiye’s second betrayal (the first was recognizing Israel in 1949). Among the Arab states, Syria and Iraq perceived this rapprochement as a threat to themselves and were concerned that it would harm their regional policy goals. Other Arab states, especially Jordan’s participation in this alliance, viewed it as the division of the Arab world into two. Furthermore, Arab states were concerned that Israel, which had strong relations with Türkiye, could be a harsher bargainer on the Palestinian Question.

At this point, it should be remembered that relations between Arabs and Turks have never been smooth. The studies of Prof. Dr. Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu also show that the image of the Ottomans in the Arab world is extremely negative. On the other hand, Ibrahim al-Daquqi’s research shows that prejudices against Arabs are widespread in Türkiye and the betrayal of World War I has never been forgotten. In this context, Arab researchers conceptualize relations between Türkiye and the Arab world in four periods:

1923-1945: Years of alienation,

1945-1960: Years of alienation and conflict,

1965-1975: Years of relative improvement in relations,

1975-1985: Years of Arab power and dramatic change.

In this context, although İsmail Cem and many other Turkish statesmen emphasize that relations with Israel are not developed to replace relations with Arab countries, a dualistic system of thought has generally developed in the public eye on this issue, and there has been a presupposition that those who love Israel and those who support close relations with Israel do not love Arabs. Due to this widespread belief, the reaction to the rapprochement between Türkiye and Israel generally comes from circles close to the Arab-Islamic world.

The Palestinian Cause undoubtedly constitutes the biggest fault line in Türkiye-Israel relations, along with the Kurdish Question. The Turkish people have an emotional approach to this issue, and the harsh policies implemented by Israel create reactions in the public opinion and the media. Türkiye’s stance on this issue can be expressed as resolving the issue through peaceful methods and based on two-state status within the 1967 borders.

Another important factor in Türkiye-Israel relations is Iran. Iran transformed into a completely different regime after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Iran’s growing strength and its ability to control regional countries with its Shiite crescent policies are bringing Israel and Türkiye, as well as Israel and Arab states, together on an anti-Tehran line.

General Assessment